INDIA :

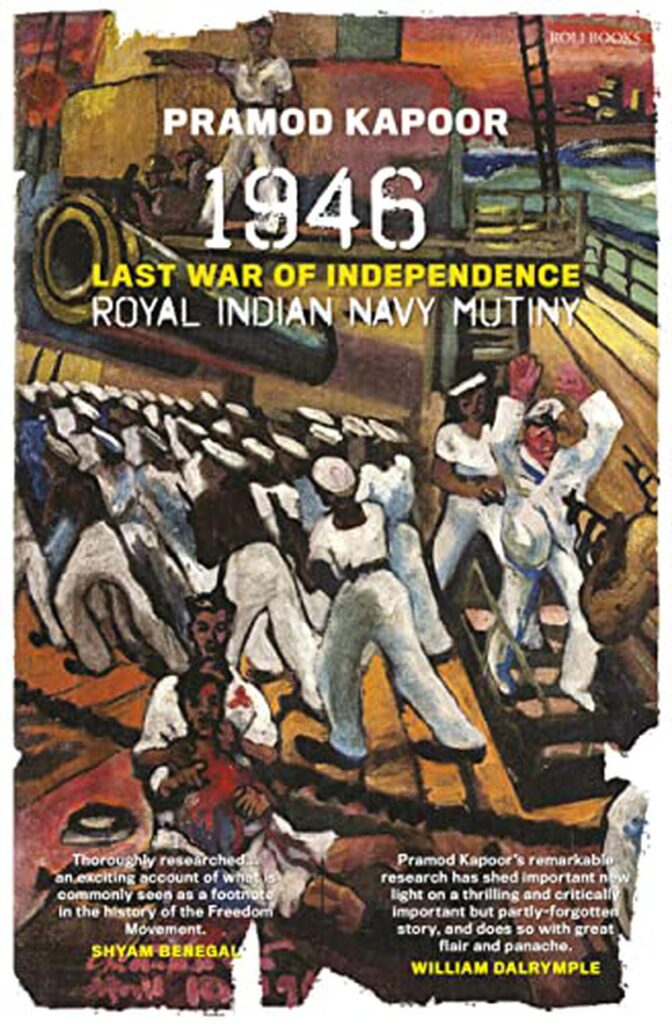

Pramod Kapoor transforms a footnote in history into a remarkable account of a rebellion that convinced the British it was time to leave India

As rightly remarked by Shyam Benegal, a footnote in the history of the freedom movement has been turned into an exciting and important account in Pramod Kapoor’s 1946 Last War of Independence: Royal Indian Navy Mutiny. Pramod himself stumbled onto this forgotten story while researching for his book on Gandhi: “After the draft of the Gandhi book was done, I re-read the Royal Indian Navy mutiny episodes and realised the magnitude of the event.”

Reports of the revolt

When Pramod began his research, he discovered hundreds of reports by British admirals, commanding officers of ships and shore establishments, cables and letters exchanged between London and Delhi, proceedings in the British parliament and debates in the Legislative Council in India. They were “honest,” but were told from the British point of view. For another view, Pramod waded through hundreds of newspaper reports and documents at libraries, met people with knowledge of the revolt and toured HMIS Talwar, the signal school of the Navy at Colaba, where “inflammatory slogans” had been written on the walls and “seditious pamphlets” were circulated. A tour of the dockyard and areas of Navy Nagar in Mumbai helped him understand the “history and geography of the area where the uprising took place.”

In February 1946, ratings, or the lowest rung of sailors in the Royal Indian Navy hierarchy, staged a revolt. The young sailors were protesting against the fact that things they were promised at the time of recruitment had not been honoured: living conditions were horrible; the food worse and there was rampant racial discrimination. Also, says Pramod, inspired by the Indian National Army (INA), they were politically charged and keen to play a part in India’s freedom movement. Within 48 hours, the strength of the mutineers grew to 20,000, and they took over ships afloat and on-shore establishments. Servicemen in the army and air force, and civilians joined the protests.

The sailors pulled down the White Ensigns of the Royal Navy and hoisted three flags — the tricolour of the Congress, the green of the Muslim League and the red of the Communist party, writes Pramod. Their demands included the release of all Indian political prisoners and soldiers who had fought in the Azad Hind Fauj. There was a direct connection, says Pramod, to the INA trials which were going on at the time. In days, the British put down the rebellion with a “combination of brute force and guile.”

Pitched battles were fought in Bombay and Karachi when the British tried to wrest back control of the ships and naval establishments from the sailors. Indian soldiers were reluctant to open fire on fellow Indians. Thus, contends Pramod, though the rebellion was put down, the British realised that it was time to quit India.

For Pramod, however, the politicians did not exactly cover themselves in glory. “They actually helped the British put an end to the uprising, despite widespread sympathy for the ratings across the nation.”

The promises Indian leaders made to the sailors at the time of surrender were not kept, he points out. Pramod also strongly believes that Partition “would have been less bloody if the political leaders had tried to build upon the communal unity created by the events of February 1946 instead of ignoring it.” This had been the view of the firebrand socialist and freedom fighter Aruna Asaf Ali as well. Even after Independence, there have been efforts to “blot out memory of the mutiny,” so much so that the Bengali thespian Utpal Dutt’s fictional play based on it, Kallol (Commotion), faced “obstruction and unofficial censorship.”

Before the protest

In the run-up to the uprising, the British were conducting the open trial of three Army officers of the INA — Prem Kumar Sahgal, Shahnawaz Khan and Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon. “Putting a Hindu, Muslim and Sikh jointly on trial at the Red Fort at a time when most Indians were deeply sympathetic to the INA meant that three major communities stood unitedly behind the call for Independence,” writes Pramod.

But leaders of the Congress were of the view that their idea of a peaceful culmination to a freedom struggle and smooth transfer of power would have been lost if an armed revolt succeeded with undesirable consequences. Thus, it was not an easy situation for political leaders to close ranks with the ratings.

Pramod has done a commendable job in going into all aspects of the rebellion. In the chapter titled ‘The Gathering Storm’, Pramod narrates the genesis and warnings of the brewing revolt. The unjust manner in which the British had treated the INA officers stirred anger and resentment, particularly at the signal school of HMIS Talwar, where the sailors were from a better educational background, and aware of the “rebellious activity taking place beyond the high walls of their barracks.” One of the villains was surely Commander Arthur Frederick King whose rude behaviour and “foul, racist language” sparked the protest at HMIS Talwar. As Talwar was the centre of all communication, the spark soon became a fire, with the strike being disciplined and well-organised.

The chapter, ‘Planning the Mutiny: The Secret Heroes’, reads like a thriller. The initial planning took place in a flat belonging to Pran and Kusum Nair on Marine Drive. The Nairs were friends with two of the key planners, Rishi Dev Puri and Bolai Chandra Dutt, and Pramod profiles the “heroes of the mutiny” in great detail.

He also adds an extensive Epilogue providing a glimpse of the life of the key protagonists post-uprising as also notes on some of the ships and shore establishments. It is an exceptional book and a must-read for anyone interested in the freedom struggle.

1946 Last War of Independence Royal Indian Navy Mutiny; Pramod Kapoor, Roli Books, ₹695.

The reviewer was with the Indian Navy during the Bangladesh liberation war.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by KRA Narasiah / May 07th, 2022