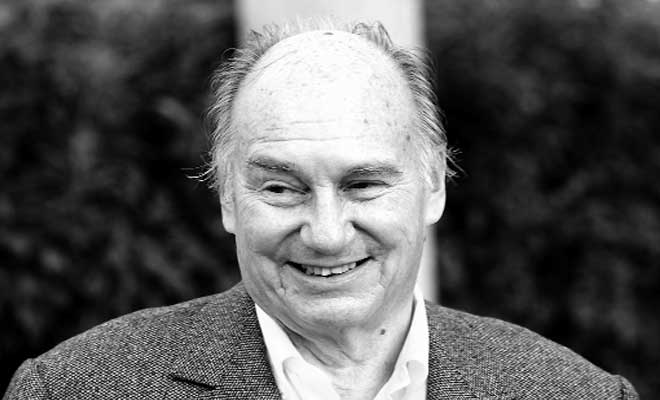

In this Walk the Talk on NDTV 24X7 at his foundation’s latest initiative, the Aga Khan Academy near Hyderabad, His Highness the Aga Khan talks to The Indian Express Editor-in-Chief Shekhar Gupta about the growing Shia-Sunni tension that worries him, and the roots of the lack of understanding between the Western and Muslim world. However, he adds, most of the conflicts one sees today have little to do with faith but have a political dimension.

It’s been said about you that no human being today bridges so many divides as gracefully and as powerfully as you do. And how many divides: the East and West, Islam and Christianity, material and the spiritual and, if I may add, ancient to the medieval, the modern and the future.

Thank you very much and I’m very happy to talk with you.

And welcome to a country which is in many ways your homeland.

Yes, yes. My grandfathers… way back.

He was born in undivided India.

He was, and the place where he was born is still there. Still in the family.

And the first school set up (as part of the Aga Khan network) was in India.

In Mundra (Gujarat).

And now there are 80-90,000 students… So what’s this thing about the Aga Khans and education?

My grandfather and I have always felt that education is an essential part of a community’s life, a country’s life, an individual’s life. It is the unavoidable building block for all people all around the world. This academy (the Aga Khan Academy on the outskirts of Hyderabad) is a part of that exercise.

Education is also a healer of the mind.

It’s a healer of the mind, but it’s also a way of making rational judgments. What we need in society is rational judgment. It helps evaluate, it helps position issues…

So before we get into the more profound discussion on making rational judgments in times when all wisdom is presumed to be given, tell us a little bit about the Hyderabad academy.

Some 10 years ago we started asking ourselves, ‘Where are we? What do we need?’. We came to the conclusion that there were a number of countries where secondary education was a critical issue. We decided that instead of trying to respond on a country-by-country basis, we would try to make a network of institutions to move intelligent children from one society to another, from one language to another, so that we would try and build global capacity and bring it in at the secondary level of education, not retard it until tertiary education or career.

And an academy like this is not limited. Access is not confined to your followers or only people of one faith?

No, no, not at all.

Purely on merit?

Purely on merit and, it goes further than that, it’s ‘means blind’. So the moment a child is qualified, it’s our responsibility to find the ability to fund that.

I haven’t heard this wonderful expression before, ‘means blind’. It’s fascinating to hear it from somebody who doesn’t like the word ‘philanthropy’.

Well I think philanthropy is very close to the notion of charity. And in Islam it’s very clear — Charity is desirable, necessary, but the best form of charity is to enable an individual to manage their own destiny, to improve his or her condition of life so that they become autonomous.

I remember something you said in an interview. You said becoming an imam doesn’t mean you distance yourself, you renounce the world. It actually means engaging with your community even more, improving their quality of life and giving them protection. It doesn’t mean sanyaas, if I may use something from the Hindu way of life.

No. And it’s not just in the Hindu way of life, there are Christian schools where engaging in life is not desirable. In Islam that doesn’t exist. It’s the contrary actually. Imams are responsible for the security of their community, for the quality of life of their community — they must engage, but they have to engage ethically.

You make a very unlikely imam. You don’t look like one — as we know the stereotype now — don’t talk like one, don’t act like one. And don’t play like one — you still suffer skiing accidents.

If you look at the life of the Prophet, he led a normal life. And in a sense he showed that Islam is part of life. It’s not separated from life.

And that’s the inspiration for you.

It’s what I believe to be correct.

And that’s what should apply to all Muslims.

All Muslims, I think, live in the real world. I don’t know of many leaders who have removed themselves totally from life. It’s not part of our religious tradition.

What about the Sufis, the dervishes?

The whole domain of mysticism, as we all know, it exists in many, many, faiths. And that is an evidence of a personal search, not of an institutional search.

And religion and spirituality should be a personal exercise.

It’s both in Islam. It’s a community approach to life, there are community responsibilities, social responsibilities, but there are also personal responsibilities. Certainly, in my interpretation of Islam, the two must go hand in hand. You can’t abandon one for the other.

There’s another fascinating thing you said — there is no clash of civilisations, there’s a clash of ignorances. But that clash of ignorances — what someone called ‘scars on our mind’, in a different context, the Cold War — is now a reality. How do you deal with it?

I’ve used all the methods I thought I had to try and help bridge civilisations rather than have them continue to look at each other in ignorance and discover each other in conflict, and all the rest.

Why call it a ‘clash of ignorances’? Let me add something to that. If the stereotypes about Islam are today cast in stone, you defy all those stereotypes.

That’s very kind. I did my degree at university on Islamic history, so I should know…

And you went to Harvard.

So in that sense, I may have had a certain amount of comfort. But if I take what was the definition of an educated child in 1957 (when he became the imam) and ask you, what was the composition of the curriculum at that time, there was nothing on Asia, nothing on Islam, very little on Africa, if anything. The industrialised world was turning around on itself. And today you still see decisions taken between the industrialised world and the Muslim world that would not have been taken if they had known each other back then.

If I can take a little chance and be sort of indiscreet, in a way the Islamic world knocked at the doors of the Western world — in the form of those planes slamming into the World Trade Center buildings.

Yes…

I’m oversimplifying.

Well it would be difficult to associate what we call the Ummah — the totality of the Muslim world — with that. I don’t think that would be right.

But that stereotype did get built.

That stereotype did get built, without doubt. But I don’t think you can attribute that to the totality of the Ummah. That’s simply not correct. So the stereotype itself is massively incorrect, which then raises another question: what is the form of communication we’re living in? How can miscommunication be as acute as it has been?

What do you tell your friends in the Western world about their new stereotypes of Islam? And what do you tell your Muslim brothers and sisters and followers about their stereotypes of the Western world?

Well I would start by asking a very simple question: in 2013 — what is the definition of an educated person? The knowledge that that person requires is more and more understanding the world, not understanding little parts of it. Understanding the world is a massively complex goal, but I think that we’ve got to admit that that’s what’s necessary. It’s unavoidable. We’re more of one world than ever before.

Because your community has also suffered, it has now come to be represented by people of a certain kind. People who hog the headlines, sort of prime-time TV, and whose silhouette usually has as an AK-47 or worse. How much damage have they done to your community?

I don’t think the community is seen as a community that is in any way engaged in this sort of concept.

Because a Muslim passport at a Western airport… I’m again using a stereotype, but it is a reality.

Well I’m not sure that is really true of all Muslims. I think there are certain areas of the Muslim world which are more, let’s say, questioned than others, but I don’t think that’s universal. And that has happened in other faiths — let’s be quite clear.

Absolutely. The Muslim world, the Ummah exists in so many countries. Your own followers are all over the world, including India.

There exists right there a fundamental point. Unless you understand the plurality of the Ummah, you are not going to think correctly with regard to that part of the world. You need to have a basic understanding of its pluralism. We are, in our part of the world, as pluralistic, if not more pluralistic, than others.

source: http://www.indianexpress.com / The Indian Express / Home / by Shekhar Gupta / Tuesday – October 08th, 2013