NEW DELHI :

In Ira Mukhoty’s narrative, Emperor Akbar is an able reformer, the earliest advocate of inter-religion dialogue, and marked for greatness because of his quality of empathy

Charismatic, curious, catholic, compassionate — Emperor Akbar (1542-1605) has long exercised the imagination of Indians of all hues. For the lay person, he is the lumbering giant with the booming voice and grand moustache as depicted by the actor Prithviraj Kapoor in K. Asif’s magnum opus Mughal-e-Azam (1960); while ostensibly a love story between Akbar’s son, Salim, and Anarkali, the film belongs to the father in the eponymous role of the Great Mughal.

For the liberals, Akbar is the embodiment of pluralism, multiculturalism and the earliest advocate of inter-faith dialogue.

For the right-wing ultra-nationalists he is the most ‘tolerable’ of all the Muslim rulers for his reverence for all faiths and abolition of the religious tax, jiziya, from non-Muslims.

An Indian icon’

From school textbooks to the Akbar-Birbal qissa-kahani to popular culture, Akbar has consistently remained an Indian icon.

Several books too have been written on him, both by the professional historian and by non-academic but extremely engaged and passionate writers. In the latter category are two recent books, both eminently readable and both written by journalists: the simply-titled Akbar by Shazi Zaman and Allahu Akbar: Understanding the Great Mughal in Today’s India by Manimugdha Sharma. Ira Mukhoty’s gargantuan book is nevertheless a welcome addition.

However, her assertion that “few full-length biographies have been written in recent times” is not entirely true. One is also wary of the sub-title; “definitive” biography sounds like a publisher’s overkill, for a book’s size alone (over 600 pages) cannot define its scope nor ward off any future explorations on the subject.

Given the absence of Endnotes, Bibliography and Index in the uncorrected proof copy sent for review, one is unable to fully gauge the extent of sources and primary texts studied by the author and whether, if at all, she has accessed Persian sources that have largely been beyond the reach of non-academic writers relying as they do on English translations.

One is, however, struck by two curious omissions by the author. One: footnotes to indicate where quoted matter is sourced from.

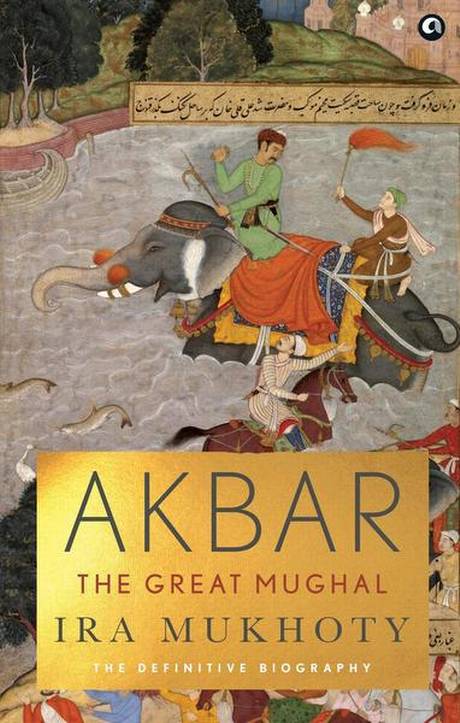

Two, a similar omission in the photographs of Mughal miniatures; more detailed captions and information about sources would have been helpful given, especially, that the book focuses on the role played by the royal ateliers (tasvir khanas) in chronicling the lives of the royal patrons and leaving behind a vast visual archive of Mughal history, a rich load that is now being mined by art historians as a supplement to recorded history.

Access to a king

Mukhoty’s strength as a writer lies in her ability to recreate a scene, flesh out characters, find the human element, in a word, narrate history.

Her previous book, Daughters of the Sun: Empresses, Queens and Begums of the Mughal Empire, contained ample evidence of her sophisticated prose and her felicity in providing a luminous account of the many women who lived in the shadow of their men yet led remarkable lives during the Mughal period. Here, too, she impresses with her ability to make history accessible in ways that professional historians sometimes don’t, or can’t.

Mukhoty shows her mettle as a narrator virtually from the opening paragraph where she describes two young hostages, a young Akbar and his sister, on their way to meet their uncle Kamran: “In the frigid mid-winter of 1544, two children were sent north from Kandahar to Kabul, 500 kilometres away. While the snow fell silently and relentlessly on a desolate landscape, the small party stumbled on through the mountain passes and ravines, their horses’ steaming breath loud in the night.”

She goes on to chart the growth of that terrified child upon whom the weight of being Emperor of Hindustan is thrust at the tender age of 13 when his father, Humayun, dies unexpectedly: “In fact, Akbar was a distracted, undisciplined, rambunctious child and youth who, in the parlance of the twenty-first century, may have suffered from an attention-deficit disorder. So unruly and self-willed was Akbar that no tutor was able to hold his attention and he grew up effectively unschooled and practically illiterate.”

Pioneering genius

And yet this young emperor would evolve into a fine human being, a patron of the arts, initiator of some of the greatest works of translation not to mention a pioneer in ship-building, metallurgy, alchemy, military technology as well as administrative reforms. Mukhoty shows us the man behind the emperor who brought in the largest territory — after Ashoka and his Mauryan empire — under his control.

Despite Akbar’s intellectual curiosity, his epiphany at the age of 36, his visionary idea of sulha kul (universal peace), it is his compassion and empathy that marks him for greatness. As he said in one of his proclamations: ‘The best prayer is service to humanity.’

Akbar The Great Mughal: The Definitive Biography; Ira Mukhoty, Aleph, ₹999.

The reviewer is a writer, translator and literary historian.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by Rakshanda Jalil / June 13th, 2020