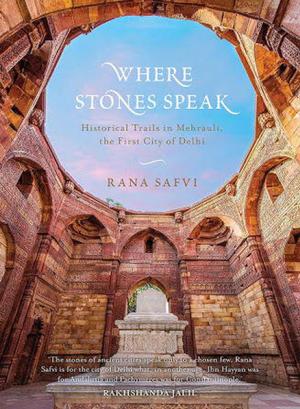

Historian and writer Rana Safvi’s blog, ‘Hazrat-e-Dilli’, is a little corner of the Internet dedicated entirely to the Capital — its new and old architecture, the dizzying variety of food, age-old traditions and much more. Her new book, “Where Stones Speak”, is another tribute to Delhi, and arguably its first city, Mehrauli. Safvi traces Mehrauli’s history through simple words and haunting couplets, takes us through its diverse monuments and weaves facts with storytelling in a way that paints a picture achingly beautiful in its richness and depth.

Excerpts from an interview:

What brought about the idea?

Delhi for us was just a transit point for changing trains to Lucknow or Nainital. Except for a visit to Red Fort and Qutub Minar with a university group I had never visited any of its beautiful monuments. It is only in the past few years when my daughter shifted here that I spent time in Delhi. I started going out for heritage walks with various groups. It was during these that I realised though there was a lot of material it was scattered and quite a lot of it was in Urdu so inaccessible to many. I wanted to write a book on the lines of Hearn’s “Seven Cities of Delhi” but when I reached Mehrauli the first city I realised that it had enough treasures to form a full book on its own. This book happened – I had set out to write something else. I feel it was blessed and willed by Mehrauli’s guardian saint Qutub Sahab.

It’s an ambitious book, one that would require you to go through reams of material. What kind of initial research did you do?

The first thing I did was to shift from Dubai to Delhi NCR as I accessed books for research. I did not want to rely on online resources only. I went through bibliographies of ASI (Archaeological Survey of India) and books written on Delhi. I went to the Urdu Bazaar. Then I bought the books. I feel I became Flipkart’s biggest customer, with books pouring in every week. I have built quite a library now and it’s ongoing. ASI itself has many books on Delhi especially on the Qutub Complex which I went through. Their library and photo section are treasure houses and I got a lot of help from them. There are many Urdu books available. A 1919 book by Bashiruddin Ahmed called ‘Waqi’at-Dar-ul-Hukumat Dehli’ is full of stories and anecdotes.

How difficult was it to find preserved records and materials for the book?

ASI publications are the best source for records and materials. Records of excavations and research done from the time of Sir Alexander Cunningham in Delhi in the latter part of 19th Century are all available with them. Carr Stephen’s 1876 book “Archaeology and Monumental Remains of Delhi” was also invaluable. Many British officers of ASI have written books on Delhi in late 19th and early 20th Century. Maulvi Zafar Hasan’s book, ‘Monuments of Delhi’, published in 1916 for the ASI details all the monuments of Delhi. Many of these are lost to us now. For contemporary history I relied on ‘The History of India, as told by Its Own Historians’ Henry Miers Elliot and John Dowson. Some of the books are now out of print or badly reprinted. I got these from the U.S. where there were second hand sellers.

Delhi’s history is a curious mix of facts and folklore. What kind of balance were you looking to provide in this book?

I have taught history in middle and senior school for many years. I know how bored people get if we just keep presenting fact after fact. I tried to use the same technique I used for my students: tell the story as accurately as I could and make it interesting. I have used anecdotes I found in my reference books as well as a few recounted to me. Wherever they are unsubstantiated by records I have mentioned that too. I have tried to enliven it by using Urdu verses which describe the stunning photographs taken by Syed Mohammad Qasim better than I ever could with my prose. It also embellishes the prose and breaks the monotony of facts. This is a style not used by any other English book on history (at least I haven’t come across it). It has been used in Urdu books though not to this extent.

What is the legacy of this past, and how you think it defines contemporary Delhi and its people?

In 1947, when India was partitioned, many of the old inhabitants of Mehrauli and Shahjahanabad left for Pakistan. The refugees who came here were shell-shocked by the trauma of being torn away from their native lands and having to start anew. For them it was survival that mattered the most. These old buildings held no meaning for them. There was a lot of encroachment those days. Those who didn’t migrate had different problems to cope with. Thankfully, the interest in heritage and our cultural legacy has once again been awakened. The younger generation is identifying with it and showing interest in preserving it. This can be seen in the wealth of books and programmes on our historical and cultural legacy.

Delhi is a juxtaposition of age old monuments and modern architecture. Do you think even by themselves these structures carry an impact?

For me every stone has a story to tell. It is up to us to tell those stories in such a way that these monuments speak to everyone. This can’t be done only through dry facts. It’s only when factual stories are associated with it that people will remember and talk of them fondly. For instance the feedback I get is that Sultan Razia’s story has made them look at Quwwatul ul Islam Mosque with new perspective. It is no longer a pile of stones but a place where a great historical event took place. Structures carry impact when we associate something which we found interesting with it. I don’t know how far I have succeeded but that has been my attempt.

source: http://www.m.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> MetroPlus / by Swati Daftuar / September 12th, 2015

2 thoughts on “Stories in stone”

Comments are closed.