Rohtas, BIHAR / Lucknow, UTTAR PRADESH :

Lucknow :

Every city in India has many iconic bookshops and Lucknow too has a few. However, in recent years, a bookshop has drawn attention of book lovers because of the variety and collection of books, particularly, in Urdu.

This bookshop has drawn readers from other states and cities too and people buy from him online as well. But the most unique aspect about this bookshop is that the passion of the owner who has been running it purely for the love of books.

Imagine, you go and find a good book and want to buy it. The bookshop owner appears sad that you chose the particular book. “I have just one copy of this book and I want to keep it”, says the man, who owns this shop. Or going to the extent of telling the visitor that they can take a look and buy from any shop elsewhere or telling the location or suggesting how to get a particular book.

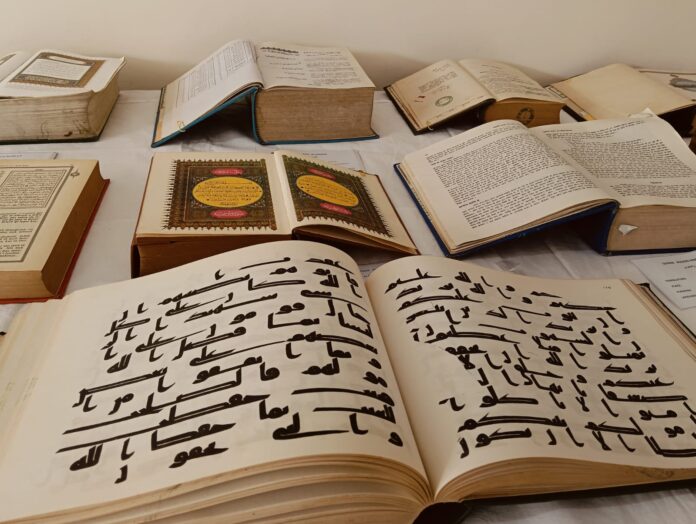

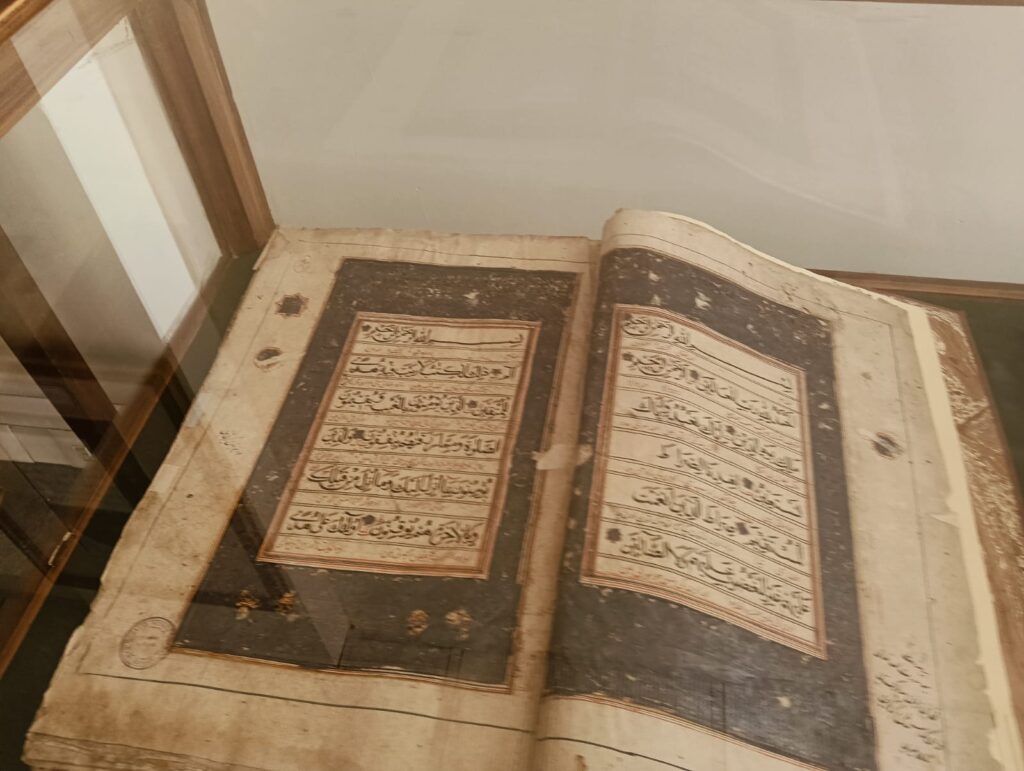

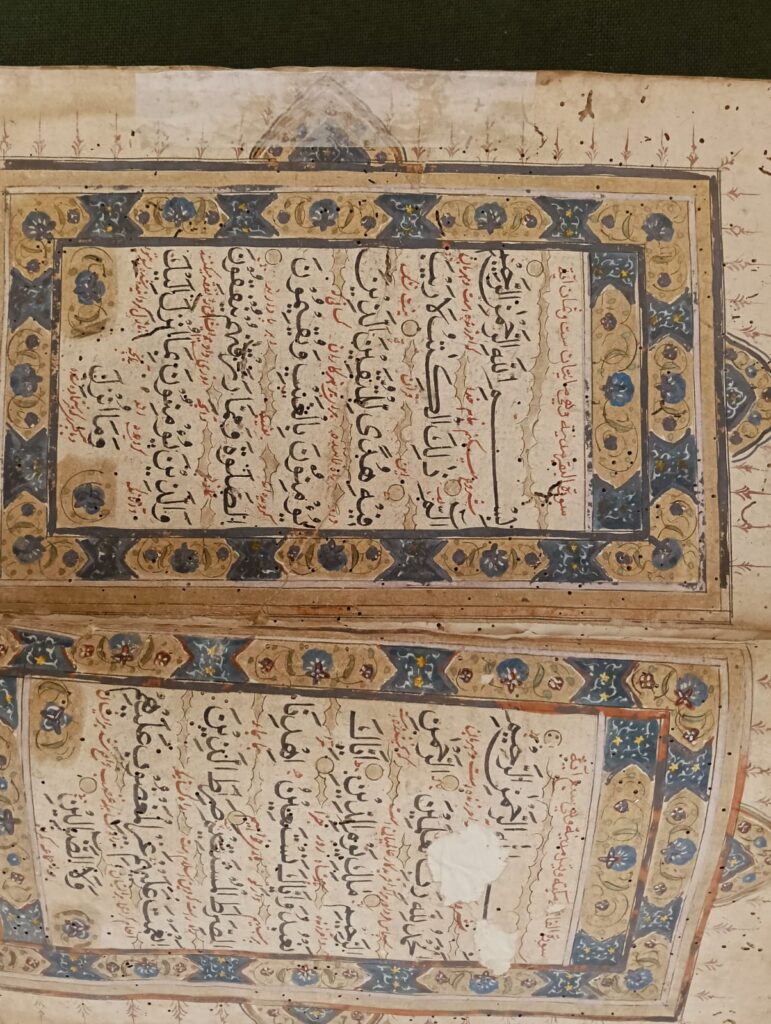

But first about the uniqueness of the bookshop. Unlike other Urdu bookshops, the owner Shahood Ul Hasan Khan keeps a very wide range of books. It’s not limited to a few publishers but he keeps books of all publications and also ensures that books ranging from all the topics are available in Urdu, ensuring a collection.

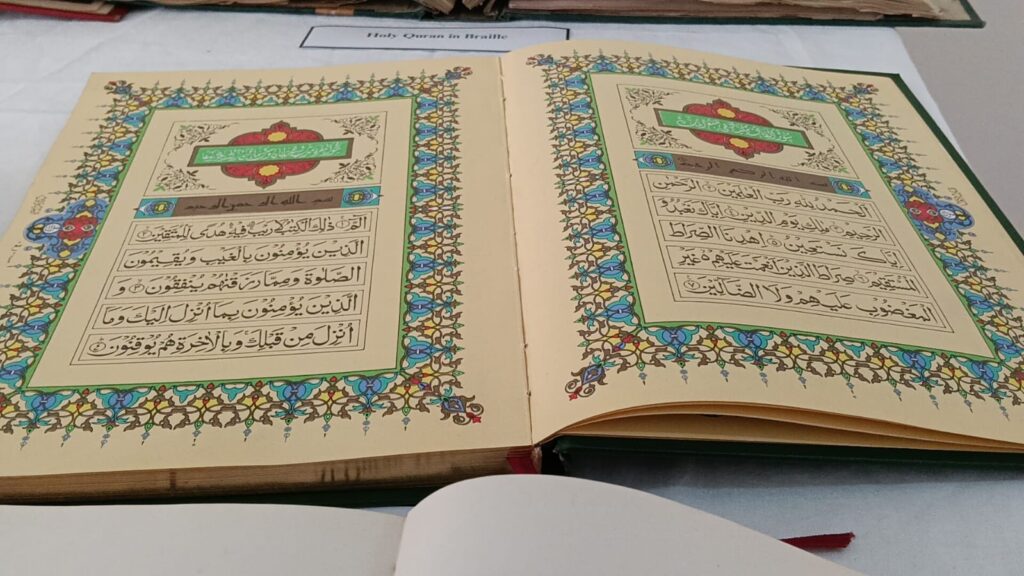

From literature to language, and law politics to philosophy, history to Islam, Hindusim and other religions, fiction, non fiction, other than books in English and Hindi too, everything is available under one roof. He tries to put on display maximum books of all variety in his shop.

“I wanted to be among books, own them and have them around me”, he says. That’s the reason he started the bookshop even though people are always suggesting that he should switch to some other business. “It’s true that I put lot of money, because it’s my hobby and passion. However, it is not a very lucrative business.

He gets lot of unwanted advices and people have finally reconciled that he would not switch to anything else, except, keeping himself amid books. People and relatives keep advising that I should give this big space to someone and the rent would be more than my current earnings, but this is my passion”, says Khan, 42, who started Parekh Book Depot, and has totally dedicated himself in this work.

“I do it for the sake of books, not for profit. I always wanted to do this and hence I am happy doing what I do”, he further adds. In a city that has iconic Danish Mahal in Aminabad and many other bookshops, the emergence of Parekh Book Depot and it’s growing popularity, has drawn attention of people.

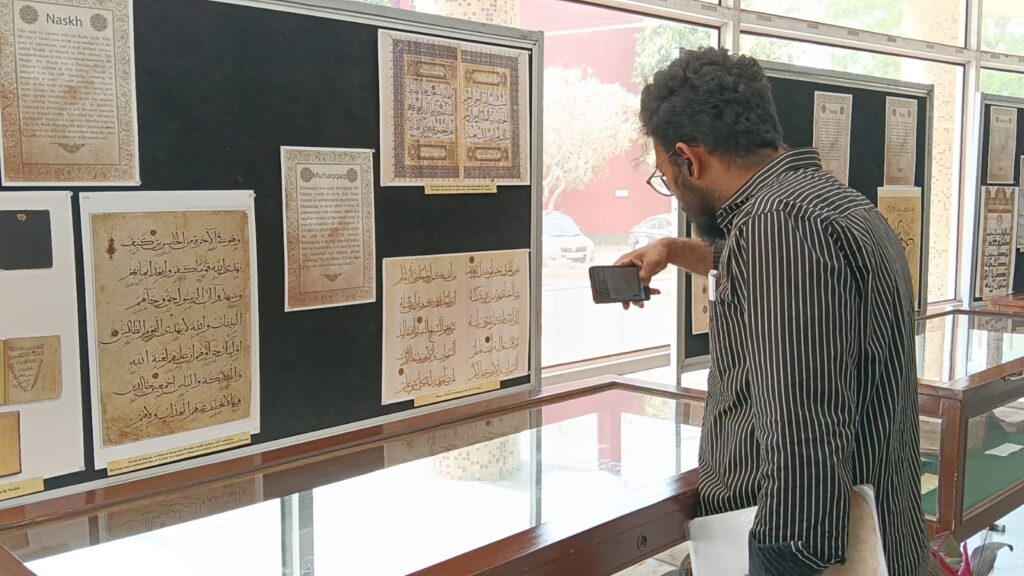

Urdu readers who come to Lucknow, try to take time out of their schedule and visit the place, as they know they might get a surprise, a rare book that was not available for long, translation of a famous English or French book or latest ones that have just been out of printing press.

As I select the books and am about to pay, he tells me that I can get these books online or from another particular place too. When I asked him why was he not keen on selling it and giving me the suggestion, he said that, ‘this set of books is not an ordinary one and we don’t know when it again gets printed and comes to market, hence, I am having a hitch and can feel that I am losing something.

At least, the set of books was with me till now”, Shahood Ul Hasan says. It was subsequently that I spoke to him and he told me about his life and his passion that has earlier been described in the report. Hailing from Rohtas in Bihar, he had come to Lucknow as an infant. He studied in the famous Nadwatul Ulema and his bookshop is also close to the gate of the seminary in Lucknow.

Many bookshops are selling just religious texts or literature. Also, there are different models. But he has shown a way, how a bookshop can thrive in an era when people keep ruing about lack of readership. “I am happy that I make enough to run my household. What else do I wish for?”.

One thing is sure, he has put in efforts and money but his passion has resulted in this bookshop emerging as an institution. It is remarkable that he opened the bookshop in 2016, and within a couple of years, it was too well known and in direct contact with readers who get details on their Whatsapp accounts about news books’ arrival and then order them through post as well.

source: http://www.newsbits.in / NewsBits.in / Home> Special / by Shams Ur Rehman Alavi / July 11th, 2023