Bengaluru, KARNATAKA :

The family had moved to England at the Queen’s behest, bringing great solace to an increasingly homesick Karim, said Mahmood.

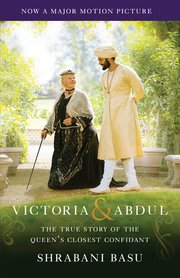

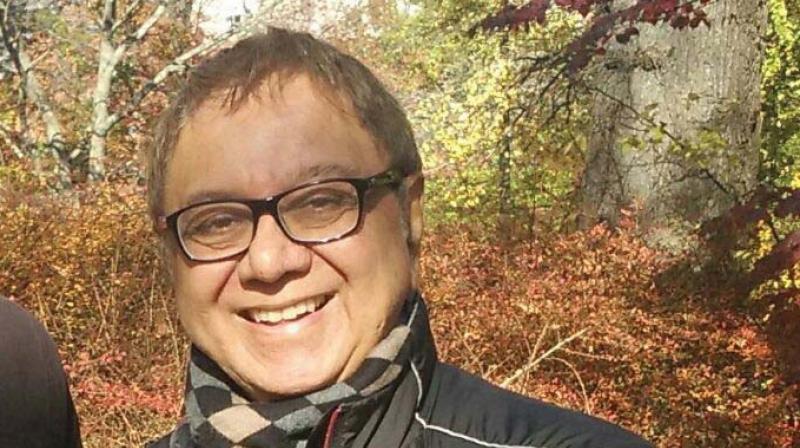

It was an April morning in Bengaluru and Javed Mahmood, as was his custom, sat down to flip through the newspapers. The year was 2010, nearly two decades since he had moved to the city to live a quiet retired life. His relatives were scattered between Bengaluru and Karachi, as they had been since Independence. Very little remained of the family’s rich history, much of what they had left was lost in the traumas of Partition and mostly forgotten. That summer morning in 2010, however, everything changed. Mahmood found, to his astonishment, that Indian author Shrabani Basu’s Victoria and Abdul: The True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant had uncovered the truth behind his great grandfather Abdul Karim telling a tale of friendship and loyalty. Mahmood talks to Darshana Ramdev about a family that has been steeped in history since, with his father, Anwar being a founding member of Bata in 1933.

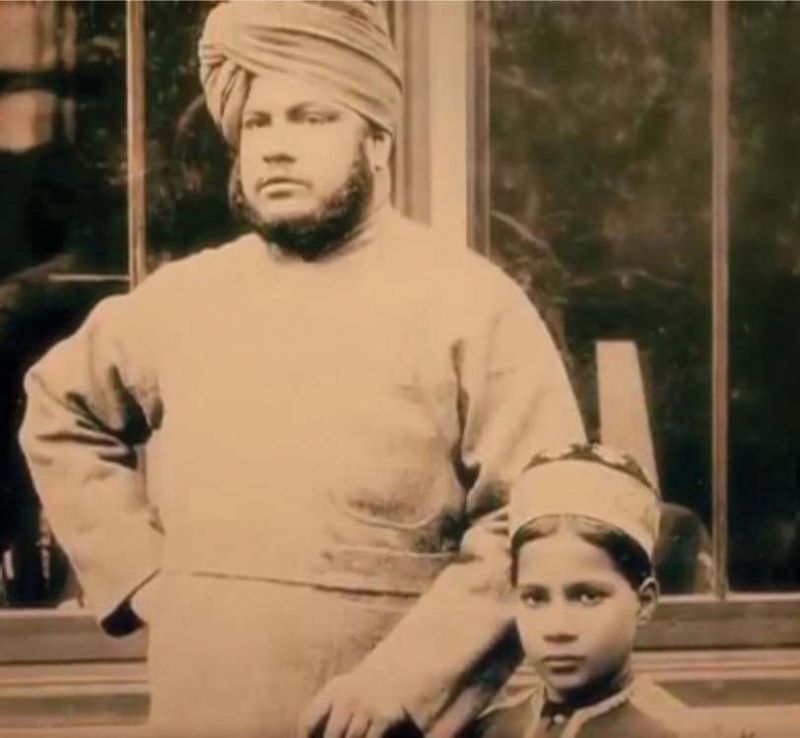

“I rushed at once to the British Council and asked them to help me contact her,” said Mahmood, whose grandfather, Abdul Rashid, was Karim’s adopted son. “We didn’t actually know he was adopted until Karim’s death in 1909 and the inheritance had to be dealt with.” The family had moved to England at the Queen’s behest, bringing great solace to an increasingly homesick Karim. “The Queen made them feel very much at home my grandfather received the same education that Edward VII and the rest of her children had earlier received.” The Queen, who was aware of the couple’s inability to have children, sent her personal physician, Dr. John Reid, to examine (much to his horror) Karim’s wife.

“Abdul Karim had been greatly maligned by historians the Queen’s family may have wanted to destroy all trace of his presence in the court. Ms Basu had gained access to hidden archives, however. Our family still had a few documents – the diary being one of them, so Shrabani and I hopped on a plane to Karachi at once!” Karim’s descendants there were understandably wary, but Mahmood succeeded in coaxing them to part with the diary. Like most people of the time, Karim maintained meticulous written records into his life, which helped set the record straight on the stream of allegations that had been made against his character. “The diary proved beyond doubt that their relationship was marked by great affection, but had remained platonic always,” said Mahmood.

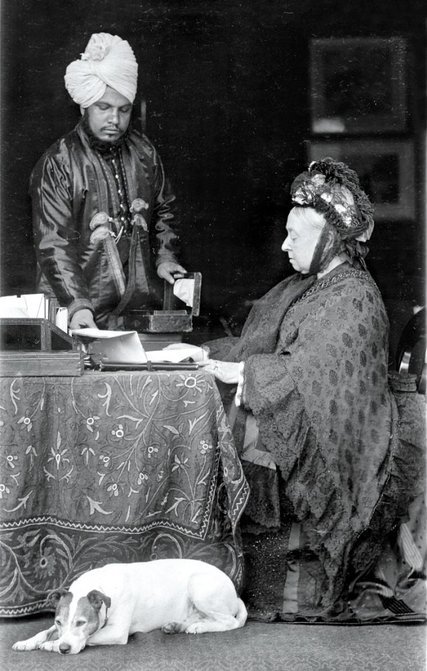

It contained valuable insights into Queen Victoria’s much loved Munshi, or teacher, the prepossessing young man who won the affections of a foreboding monarch with a reputation for a heart of stone. He was presented as an orderly to the Queen, which he didn’t like it was not a fitting position for the son of a landed ‘doctor’. He soon found himself promoted to Munshi, leading the now ailing Empress to a discovery of India. The Queen’s love for her young munshi drew jealousy, hatred and racial prejudice in a society known for its repressive puritanical leanings. Neither cared, however, with the Queen sticking her neck out on numerous instances to defend her young friend. “She was always caring and appreciative of our customs every Eid, she would walk across the grounds to Karim Cottage (on the Osborne House estate) to visit the family.” They were, in turn, invited up to the palace for tea during Christmas “The Queen would even have the windows covered with silk curtains so Karim’s family could keep the purdah. He was also a wonderful cook he would cook for her on occasion, as an act of love.”

Little was known of his life after the Queen’s death in 1901: Karim and his family were unceremoniously deported, almost at once, by a jealous Edward VII, who been aroused to such fits of rage that he had even attempted to force his mother to abdicate from office, on grounds of insanity. “Soon after the Queen’s death, King Edward arrived at Karim Cottage in Osborne House and ordered Rashid, who was a teenager at the time, to scour the house for any heirlooms or documents that contained the royal insignia. The little they could salvage, including Karim’s diary, returned with him to Agra in 1901, where he died eight years later. “He died at the age of 48 and the family was given his inheritance,” said Mahmood.

These remained with the family for some decades, until talk of Partition began to do the rounds. “We were a fairly prominent family and were advised at the time to shift temporarily to Bhopal, until the trouble blew over,” said Mahmood. This they did, greatly underestimating the scope of the problem and packing only the essentials. When the Partition took place, the family was evacuated to Mumbai, but many of the treasures were lost in transit. “The diary was with my grandfather, who was the custodian of Karim’s things.” The family moved to Karachi, save for Mahmood’s mother, Begum Qamar Jahan and two sisters. The diary went to Pakistan with them. “One of the sisters eventually shifted to Pakistan too,” he explained.

Meanwhile, in 1933, Bata, which was a burgeoning Czech company, found itself in hot water after the nation was declared Communist. The company decided to set up a factory near Calcutta, where leather was widely available. The large Muslim population in the area was another perk, providing the tannery services they so badly needed. “My father, Anwar Mahmood, was one of the founding members of the company,” he said. He joined the company at the age of 16 and worked there for nearly 30 years before he started his own business, the Trot Shoe Company. The first factory was set up in Kolkata in 1963 and the second in Whitefield, in 1970. “The organised shoe industry didn’t exist in South India and the Karnataka government had offered businesses a number of benefits, which led us here,” said Mahmood. Natural rubber, an important raw material and was grown abundantly in Kerala, making it easily accessible. “My elder brother managed the factory here, I handled the one in Kolkata and my parents shuttled between the two cities. When my younger brother was ready to start work, we established a third branch in Hosur.” Javed Mahmood and his younger brother still call Bengaluru home.

Mahmood tells his story from San Francisco, where calls have been pouring in from across the world since the release of the film, Victoria and Abdul. “The film is doing very well, it’s being shown at local theatres here as well and friends have been getting in touch to tell me how much they enjoyed it,” he smiles.

“My great grandfather’s relationship with the Queen had been presented as scandalous and sleazy he was falsely accused of every imaginable sin. Ms Basu read Karim’s diary cover-to-cover and brought those insights into the second edition of her book.” And that’s how Abdul Karim’s story received its long overdue re-telling, well over a 100 years after his death in 1909. “Queen Victoria was a woman far ahead of her times, rising well above the prejudices that so plagued her society, to defend the young Indian man she called a friend. I think there’s a lesson in it for all of us even today.”

source: http://www.deccanchronicle.com / Deccan Chronicle / Home> Nation – In Other News / by Darshana Ramdev, Deccan Chronicle / October 14th, 2017