NEW DELHI :

Taking up the challenging task of achieving unity and tolerance

Fifty-six is no age to die. Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari, MD, MS, with a tall reputation in London’s Lock Hospital and Charing Cross Hospital, and ‘free Doctor’ to uncountable poor in Delhi, was on a train bringing him back to his hometown, Delhi, from Mussoorie where he had gone to treat the Nawab of Rampur when, on May 10, 1936, a heart attack – his first and fatal – took him away. He was four years short of sixty.

Doctors are human and death’s sudden grasp comes to medical luminaries just as it comes to ordinary mortals. Ansari must have been in some disbelief at his heart’s capitulation. But his death shocked a whole world beyond himself, a world of grateful and trusting patients, former patients, friends, families of patients, countless Congress and Muslim League leaders who were his patients, some of them, and fellow freedom fighters, all. For he had been more, incredibly more, than the ‘good Doctor sahib‘. He had been, for over two decades, a political guide and pathfinder to all those who believed in India’s plural integrity and in India’s destiny as a leader of progressive causes globally.

The Balkan War in 1912 saw 32-year-old Ansari lead a medical team from India to Turkey to help wounded Turkish forces in what was not just a humanitarian act but one that formed lasting bonds, as the medical mission of the doctor, Dwarkanath Kotnis, to China in 1938 during the Sino-Japanese war was to do. The Kotnis Mission has been the subject of a film, Dr. Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani by V. Shantaram, for which K.A. Abbas wrote the script. A film has to come on Dr. Ansari Ki Amar Kahani about that mission’s work. Mrinal Sen could well have made such a film a decade ago but perhaps Javed Akhtar or Shyam Benegal will yet do it, for it cries out, filmographically and civilizationally, to be done.

M.A. Ansari’s life as such needs to be known, not for his sake – he is beyond the reach of recognition or neglect – but ours. Being invited to play a constructive political role in the formulation of the Lucknow Pact between the Congress and the Muslim League in 1916 and to preside over the Muslim League’s sessions in 1918 and 1920, Ansari emerged as a sturdy champion of the Khilafat Movement and Hindu-Muslim unity.

His commitment to that cause soon steered away from League politics, the separate electorates idea and all that was to lead to the demand for Pakistan. This resulted in his becoming inevitably, a general secretary of the Indian National Congress in 1920, 1922, 1926, 1929, 1931 and 1932 and in 1927, its president. A former president of the Muslim League becoming president of the Indian National Congress? Incredible, but incredible things did happen in Gandhi’s and Nehru’s India.

Drawing close to the Mahatma’s eclectic nationalism, Ansari became Gandhi’s ‘Delhi host’ in his old Delhi manor called ‘Darussalam’ and physician to members of Gandhi’s family, including his grandson, Rasik, son of Harilal Gandhi, who contracted typhoid in 1929 while on a visit to Delhi (from eating roadside jalebis, as Rasik himself explained) and in spite of Ansari’s valiant efforts, could not be saved. Gandhi was touring the North West Frontier at the time. Ansari sent him a telegram conveying the news. Gandhi steeled himself. “I loved the boy,” he wrote, “I had placed high hopes on him…” The trauma brought the doctor and the Mahatma closer to one another.

Ansari was instrumental in the founding of the Jamia Millia Islamia, and bringing to it a whole host of nationalists, Muslim and Hindu, to learn and to teach. In return for learning Urdu, Gandhi’s youngest son, Devadas, was recruited to teach the Jamia spinning. Ansari was Jamia’s chancellor when he died.

Liberation from mutual animosity and mistrust among Hindus and Muslims was for him a passion. Ansari was, to use an old-fashioned phrase, a man of God. He was also a man of Science. His being a man of science doubtless had something to do with his harbouring his eminently rational goal of wanting Hindus and Muslims to live in civilized amity, not conflict.

As it happened, on the very day Ansari died, Gandhi was meeting in the Nandi Hills, near Mysore, India’s most famous man of science, Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman. If a man of god can be a man of science, a man of science can be a man of god.

Raman to Gandhi: “The growing discoveries in the science of astronomy and physics seem to me to be further and further revelations of God. (But) Mahatmaji, religions cannot unite. (Only) Science offers the best opportunity for a complete fellowship. All men of science are brothers.”

Gandhi to Raman: “What about the converse? All who are not men of science are not brothers?” ( The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume 62, pages 387-9)

Within a few hours of this conversation, M.A. Ansari, man of science and of god, brother to all who came in contact with him personally, professionally or politically, lay dead in his railway coach.

Gandhi had gone to the Nandi Hills with Sardar Patel, among others, for a ‘health’ sojourn at Ansari’s behest. When the news reached him the next day, he was stunned. Penning a tribute for the Associate Press, he described him as “the poor man’s physician if he was also that of the Princes” and said, “His death will be mourned by thousands for whom he was their sole consolation and guide.” He added: “…He was my infallible guide on Hindu-Muslim questions. He and I were just planning an attack on the growing social evils.”

An attack on social evils. Strong words, scorching words. What was the biggest ‘social evil’ that Gandhi was exercised most about in 1936? Hindu-Muslim mistrust.

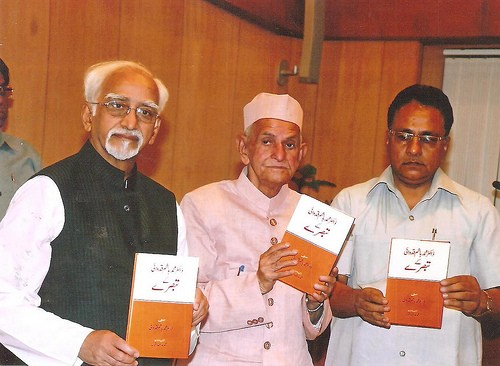

He needed a guide from among the Muslim community to tackle this. And, with Ansari, that guide was gone. At a loss to find a successor he turned first to Zakir Husain. “I ask, will you take Dr Ansari’s place?” On Zakir Sahib not agreeing, he turned then to Maulana Azad for that crucial assistance. It is entirely reasonable to suppose that had Ansari lived he would have played a defining role as a symbol, spokesman and strategist for Hindu-Muslim unity in the Constituent Assembly and then, very probably, in 1950, become president or vice-president of India. He would have been only 70, the age at which his grand-nephew, Mohammad Hamid Ansari, first became vice-president of India.

What was the main concern – ‘social evil’ – forcefully, passionately expressed in Vice-President Ansari’s farewell address to Rajya Sabha? The challenge to Hindu-Muslim unity, pluralism, not as mere ‘tolerance’ but in Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s words: cultural intimacy.

We know what Vice-President Ansari, descended from that great name in Indian pluralism – Dr M.A. Ansari – who rejected everything that led to Pakistan, has received by way of a ‘reward’.

Seventy five years after the Quit India Movement, 70 years after Independence, we the people of India, brothers and sisters in plural mutuality, must tell the shatterers of India’s unity, Hindu, Muslim and other: Quit, quit terrorizing India.

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, online editon / Home> Opinion / by Gopalkrishna Gandhi / August 22nd, 2017