NEW DELHI :

Even today, the custodians of the centuries-old Dilli Gharana of music, known for its Khayal gayaki, live and practice their art in the old, romantically named Mausiqi Manzil in the Walled City. But with changing times and commercialisation, they are experimenting with their craft to stay relevant

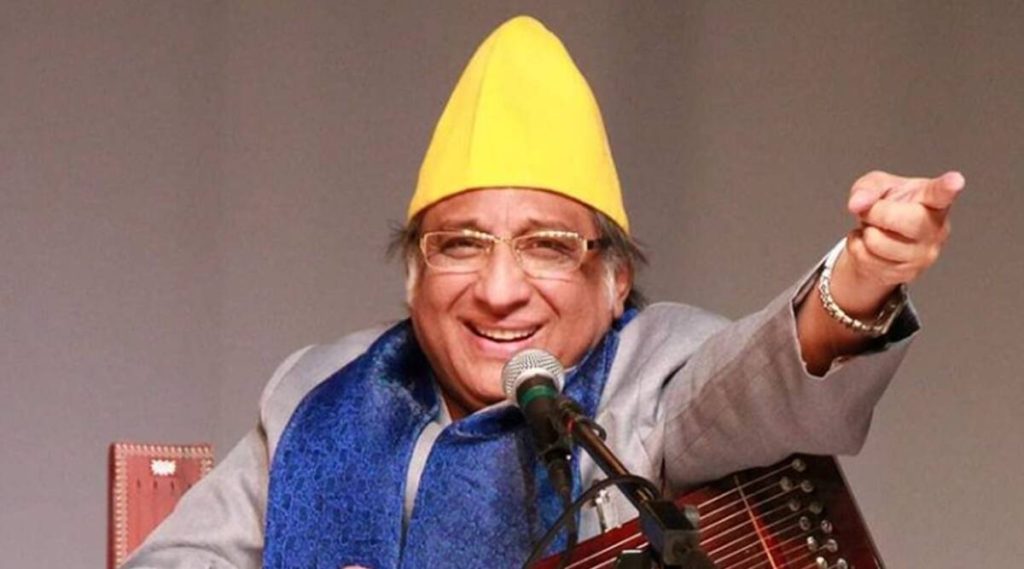

It will be too much to expect Aalif Iqbal Khan to understand the significance of being the youngest descendant of the Dilli gharana. He is five years old – too young to know the history of the family or the legacy he will have to uphold in the years to come. But the family elders seem to have already decided for him. They enjoy seeing Aalif spend time with his grandfather, Ustad Iqbal Ahmed Khan, 64, the head or khalifa of the clan, in the living room of Mausiqi Manzil, their more-than-200-year-old house in Delhi’s Walled City. They film the child when he exerts his vocal chords while sitting cross-legged on his grandfather’s chest. “Look how beautifully he sings. There is no match to his talent,” says Aalif’s mother, Vusat Iqbal Khan, 32, with pride.

Musical families across the country have seen far-reaching changes over the decades because of the evolving tastes of audiences, the death of royal patronage, the impact of technology and plethora of alternative leisure activities. Having felt the ripple effects of this transformation, the family representing the Dilli Gharana of music (gharana refers to a style of presentation) is trying to remain relevant to the times without compromising on its rich history.

The family is one of the oldest in the country to propagate the city’s Khayal gayaki – a style of singing popularised by 13th century Sufi poet Amir Khusrau. Over time, members of the clan preserved and promoted more than two dozen sub-genres of singing such as sawela, tirvat, dhamar and sawan geet. Some members of the gharana have mastered musical instruments too, such as the tabla, sitar and violin.

“It is hard to find another family which is such a rich a repository of Khusrau’s compositions. They also know the journey of the compositions and the many influences on each composition over the course of centuries,” says Vivek Prajapati, 30, Iqbal’s disciple and a PhD scholar at the faculty of music and fine arts, Delhi University.

According to Hindustani classical singer and writer Vidya Rao, the Dilli gharana strongly suggests that one of the influences on the development of Khayal gayaki could be Sufi tradition and music. “Also, it is perhaps the only Khayal gharana where the ghazal is an integral part of the gharana’s repertoire,” she says.

According to Dr Sunanda Pathak, scholar, performing artiste and author of Origin and Evolution of Raag in Hindustani Classical Music, the Dilli gharana’s style of presentation offers tremendous scope for developing ragas. “The style is taan pradhan or variation in notes is the primary ornamentation tool,” she says.

According to Delhi historian and chronicler RV Smith, “Before Khusrau, there was only bhakti sangeet in India. Khusrau combined the temple music with the music of the Arab peninsula to develop multiple genres of singing, among which, Khayal was the one mostly practiced by the founders of Dilli gharana.”

In the old days, classical artists like Siddheshwari Devi, Malika Pukhraj, musicians and composers like KL Saigal, Roshan Lal Roshan, and Mumtaz Jahan Dehlvi (much before she arrived in Hindi cinema as actor Madhubala), were regulars at Mausiqi Manzil. “In 1938, there was a conference near Jubilee cinema in Chandni Chowk, where she sang. Back then she was just Baby Mumtaz,” says Iqbal.

The narrow lane leading to Mausiqi Manzil has shrunk even further over the decades due to haphazard construction. The bylanes resemble tunnels within a tunnel. The windows of one house open into the bedroom of the facing house. Sunlight is a luxury. Goats are parked along with two wheelers, cycle rickshaws and carts. A web of electricity wires sags above passersby.

Iqbal lives with his wife Zohra, son (Saad, 22) and youngest daughter (Sadiya, 23) on the first floor. Pictures of Khan’s great grandfather Ustad Mamman Khan, grandfather and teacher Ustad Chand Khan and his brother Jahan Khan hang on the wall, silently watching the proceedings in the living room. Iqbal’s books and awards are stacked in a wooden showcase. He takes out a briefcase from a trunk. It contains Chand Khan’s manuscripts in Urdu, Arabic and Persian, and all his medals. An old, dark green pouch contains a few of his belongings, including one of his pens and even a tooth! “Babu miyan had asked me to throw it. But I kept it safely,” says Iqbal, recalling his mentor.

FILMI SONGS

Times are tough. Iqbal’s descendants perform on a freelance basis, take up teaching assignments and perform with him in regional and international concerts.

They are open to trying different formats and styles as long it is in sync with the family’s tradition. Iqbal’s first cousin and student Imran Khan, 38, was in his early 20s when he was approached for a television reality show. “Ab tum filmi gaaney gaaogey?” his mentor said. But Imran says if he got the offer now, he would accept it. “I don’t think playback singing is a bad thing. I sing for bands. In a mehfil, I sing Sufi songs, ghazals, and film songs,” he says. “Hmmm…maybe things would have been different had I participated in that reality show.”

Iqbal faced a similar situation in his youth. “Filmmaker Rajinder Singh Bedi offered me a film. I said I would be comfortable if the composition was similar to what Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sahib sang in Mughal-e-Azam. Otherwise, I was not interested. It didn’t work out,” he says.

More women in Iqbal’s clan have been to college than men. Iqbal, a graduate from Delhi’s Dayal Singh College, and his younger brother, the late Dr Anis Ahmed Khan, a music scholar, were exceptions. “I am all for education. But it cannot replace talent. And then, look at the sheer number of educated unemployed youth,” says Iqbal. After a moment, he adds. “Riyaz consumes lot of time. It does not leave any time for school and college.”

Iqbal’s family is learning to make the art form commercially viable without degenerating the guru-shishya tradition. In 2012, Iqbal’s daughter Vusat quit her job as a communications consultant with the union ministry of information & technology to help her father and add to the family’s body of work. Apart from overseeing the management of two family enterprises – the Amir Khusrau Institute of Music and the Sursagar Society – Vusat conceptualised and performed storytelling for two productions (Rudad-e-Shireen and Ghalib, Umrao Ki Nazar Se). “I realised that my family members were not getting the exposure they deserved. Also, they have a classical music mindset. It is a good thing. But these days, you have to contemporise to become commercially viable. It is the need of the hour,” she says.

The experiments didn’t come about without disagreements. Sometime in 2015, she was designing a performance of Indian classical vocal and instrumental fusion. Her father did not want to compromise on certain elements. His apprehension was that adding instruments might lead to confusion. “He belongs to the era when the world was straightforward and transparent. But we have to look at the commercial aspect as well. It is very difficult to convince abba ji. But eventually we manage,” she says.

Iqbal says he does have a sense of changing times. “In the beginning, our forefathers had the patronage of royal families. Then came the Nawabs. Now, mass media takes us places.”

US AND THEM

The family members continue to face prejudice in varied degrees in their neighbourhood. Their customs often leave people bewildered. Touching the feet of elders, especially gurus is the norm; there is no fuss about singing Sai bhajans at private gatherings; Iqbal and his students celebrate Holi, Basant Panchmi and Guru Purnima at the institute. They don’t perform during the first 10 days of the month of Muharram because they mourn the martyrdom of Prophet Muhammad’s grandson Imam Hussain – a practice that makes them appear close to Shia Muslims. “Singing and music have no religion,” says the khalifa.

Sitar player Adnan Khan, 25, is Iqbal’s nephew. After learning the sitar from his father, Ustad Saeed Khan, Adnan was at the ITC Sangeet Research Academy, Kolkata, for five years to polish his craft. He remembers the caste slurs hurled at him in the neighbourhood in his early teens. “We were told to ignore remarks such as meerasi, pandit, and we did. But there were occasions when it led to arguments. The situation is very different now. Many of my friends are from non-musical backgrounds,” Adnan says.

FINDING SOUL SISTERS

Miyan Samti, Amir Khusrau’ contemporary and grandson of vocalist Hasan Sawant finds mention in the shijra or family tree of the Dilli gharana. Samti’s descendant Miyan Achpal Khan, the khalifa of the tradition in the early 19th century, was the court musician during the reign of the last Mughal king, Bahadur Shah Zafar. Later, Iqbal’s grandfather Ustad Chand Khan became the khalifa.

Chand Khan didn’t have a son. He raised Iqbal like his son since he was three months old. His formal training began at the age of four with soz khwani or songs of lament. In later years, his day would begin at dawn with warm-up exercises which comprised of squats. Then he would practice sapat (straight) taan on prayer beads “It had 500 beads. We had to finish six strings every morning,” recalls Iqbal.

During his training, he met Krishna Bisht and Bharti Chakravarti, two disciples of Chand Khan, who became Iqbal’s guru behenein (sisters). Bisht, former dean at faculty of music and fine arts, Delhi University, is the senior most living disciple of Chand Khan.

After Chand Khan’s death, Iqbal was declared the khalifa or the representative of the Gharana in February 1981.

Iqbal avoids performing at gatherings where art is considered as entertainment. “We perform for people who know our history,” he says.

Back at Mausiqi Manzil, the new generation is preparing to take on the mantle. Vusat’s youngest sister, Sadiya, a post graduate in political science, may soon become the first woman of the family to sing on stage. “Somehow, women could not get to sing on stage. I doubt if they tried. Sadiya is not a trained singer but she has got a very good voice. Men in the family were particularly surprised when I said she should perform. Battles within the family are more difficult than the ones outside,” says Vusat.

source: http://www.hindustantimes.com / Hindustan Times / Home> Art & Culture / by Danish Raza , Hindustan Times / October 27th, 2018