UTTAR PRADESH / NEW DELHI:

New Delhi :

With roots in Uttar Pradesh, both these Delhi-based artists come from families whose values can be traced back to the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb. Growing up during the 1990s, visual artist Taha Ahmad and theatre practitioner Wamiq Zia carry a nostalgia where a composite culture that was celebrated across the length and breadth of the country, where cultural identity was always stronger than the religious one.

The ‘Urdu Poetry Project’ is a manifestation of the belonging of the two individuals who come from a world where individuals were identified on the basis of the language they spoke, and not their places of worship.

An ode to Urdu poetry, the common passion shared by the two artists, the project sheds light on how the language is looked upon today, under the pretext of the current socio-political context in India.

Fifteen Urdu poets have been chosen ranging from Amir Khusro to Faiz Ahmad Faiz, and they intend to follow this project with more multi-arts projects based on the other forms of literature.

Essentially, the idea for this project came from the evening conversations, the two artists would have, with most of them being focused on literature and specifically around Urdu poetry.

Being the practitioners of their own arts, all these discussions were full of ideas around the different ghazals and nazms and how the two artists looked at them from the perspective of the art forms that they practiced.

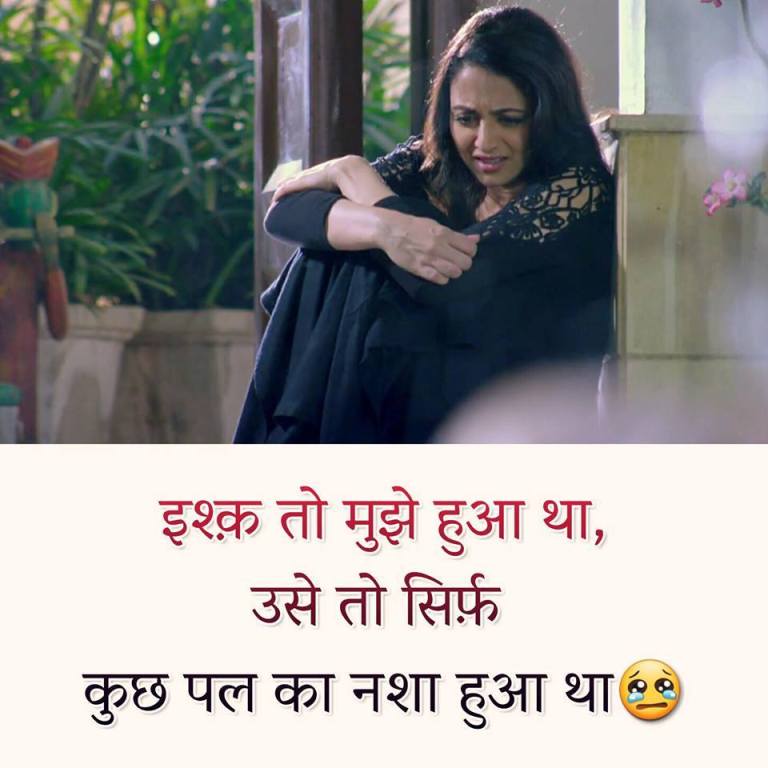

“We have tried to visually represent the journey of Urdu poetry across the ages, in a free-flowing manner creating a historical timeline. The fusion of the different art forms is visible in the way these art pieces are being designed. Through carefully curated photographs, the project tries to visually represent 15 couplets by the 15 greats of Urdu poetry chosen for the project. The photographs are a modern interpretation as well as a representation of the couplets chosen set in today’s timeline amidst the current socio-political state of the language,” Zia, who has actively been doing theatre for the past 15 years and writes for OTT and films tells IANS.

The photographs when put together as a series will take the form of a personal letter written by a father to his daughter, the father will be a metaphor for the composite culture that the society has been a witness to, whereas, the daughter will be one for the new world.

The letters will present the father’s wish to share his legacy with his daughter. Its parts will be written by different calligraphers on each of the photographs.

Considering Urdu calligraphy and script have witnessed a massive decline over the past decades, this will be an ode to the two arts by the creators of this project.

Every photograph will have a part of the letter that talks about that era, the story of the language, and the legacy of the couplet, hence, an attempt is being made to narrate a complete story through each of these photographs.

Ahmad, the first Indian to receive The Documentary Project Fund/Award (2017) and Toto-Tasveer Award for Photography (2018) says art has always been an effective tool of resistance and highlighting issues.

“There is always a purpose behind creating an art piece that addresses certain political and social issues. Or reinterpret different social structures of the society offering alternate understandings of certain events and dimensions. All of this put together becomes a force of political and social change. The potency of an art piece lies in its capacity to transcend cultural, and linguistic barriers. Let us not forget art has a purpose — to comment on society, and what is going on around us. Raise awareness about different horrors. Interventions like these are a statement and commentary on societal issues,” adds the visual artist.

Stressing that artistic interventions have become important in the face of contemporary socio-political trends, the theatre artist also feels they are non-accusatory in nature and non-confrontational. “I am talking to the audience in a language that we both speak in and that is why poems and songs and art pieces become a rallying point in social movements. Art has always been a rallying point for the common man and some of the best art pieces have been written then and instead of fighting, we should put up a mirror and take a call for what we want to do.”

In times when languages are being interlinked with religions, the artists say it must be remembered that language is a representative of culture, and culture and language are two very different things.

“Krishna has been narrated in Urdu more than any other language and it is important to see things in perspective, that’s the point of a project like this and we want to keep hitting the nail and communicating that and I don’t know how much of an impact will it make but if we can get people to talk about it then I consider us successful,” Zia smiles.

Both artists have known each other since 2015 and worked on many ideas together including film scripts. “In between different ideas is how ‘The Urdu Project’ was born. And it is not only about us, but also our team Niharika, Ashi, Azad, Shariq, and KD. Well, the project has been a roller coaster and we have plans of massive projects and with bigger casts as well,” they add.

Even as artists are breaking silos and increasing collaboration across genres, like in their case, Zia says the same ensures diverse ideas, perspectives, and approaches to the table. “This cross-pollination of ideas, creativity mediums, and processes leads to fresh interpretations and novel techniques. I am seeing unconventional artistic solutions to problems in society. While this is not something very new, but offers immense possibilities nevertheless.” — IANS

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home> Culture / August 31st, 2023