Hyderabad, ANDHRA PRADESH (now TELANGANA) :

by Geeta Doctor

| “He never ever mentioned his life with the INA, let alone the story that he had been the one to coin the greeting ‘Jai Hind’. To the rest of the world he might have been a freedom fighter, but to us he was always `Uncle Safrani’.” |

To the rest of the world he might have been a freedom fighter and a soldier who fought alongside Netaji, but to us he was always “Uncle Safrani”.

Only much later did we realise that his real name was Zain-al-Abdin, or Abid Hasan as he preferred to call himself and that the stories he told us of his days in the Indian National Army were actually true.

“Compared to us, Safrani was a man of the world,” says my Mother looking back on the first time they met him, in 1948, on board a ship that was taking them to start the first of the Embassies that were just being opened.

Safrani was bound for Cairo, my parents were due to get off at Genoa and make the rest of the trip by land to Paris.

What they did not know then, was that they had been booked on a cargo ship. Some cabins had been hastily converted to accommodate First Class passengers. It would take the long route, going up the Persian Gulf, stopping at various ports to unload goods.

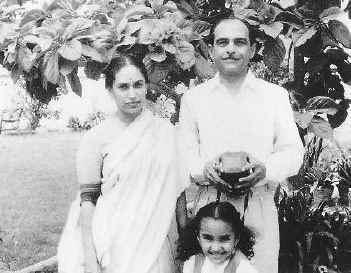

For my young parents who were leaving the country for the first time, with two small girls, my sister Surya who was two years old and myself, who was five, on a ship belonging to the Sindia Steamship Company as it was known then, Safrani was a wonderful guide. They had never left the shores of India.

He on the other hand was not only a member of the old Hyderabad elite, but had also studied for a while in Germany and travelled all over South East Asia, as Secretary to Subhas Chandra Bose.

“Safrani was one of those men who could make friends with all kinds of people. He was all over the ship. When it docked he would be the first to get off and go straight to the bazaars and return by evening with all manner of beautiful things. He was also a scholar who spent long hours with his Persian and Urdu poetry. There was nothing he did not know and seeing how raw we were, he made it his business to educate us in all the finer points of life. For instance, when we docked at the port of Basra he ran ashore and bought so many carpets that he ran out of money. But this did not worry him, he just made arrangements to borrow money on credit so that he could buy more. ” recalls my Mother.

In the evenings when the ship was at sea, he would take us to the top most deck and point out the stars to us and whisper stories to us about all the ancient sailors like Sindbad who had crossed these very seas. To us, he would become like Sindbad the Sailor himself. During the day, dolphins would follow us racing by our side, while as we made our way into Aden, where the local Indians received us like fabulous guests that had been sent by the newly Independent government of India to conquer the world, Safrani showed us how to be gracious in accepting the hospitality of strangers, who could also be family.

At Port Said, he transformed himself into an Arab prince, bargaining with the chattering hordes of intrepid vendors who climbed up from their small boats into the ship, teaching my parents to sip bitter coffee from small glasses and to taste the sticky sweet lumps of baklava.

By the time the ship sailed into the Mediterranean, Safrani had become the perfect European gentleman, as debonair as David Niven, as effusive as Signor Peperino, with his flowing moustache and his ability to charm the ladies, with his manner of bowing down to kiss a hand. Or as was the case with us to imprint our tender young cheeks with moist and noisy lip-smacking kisses. He became for us the kissing Uncle.

It was also a way in which he kept track of some of his possessions, the beautiful carpets, the pieces of porcelain and small paintings that he had left with us, just as a token of his friendship he said. “I want you to enjoy them as long as you like and when I need to sell something , I will come and collect a carpet or two.”

We were the guardians of his generosity. For though he bought beautiful things with the lavish style of an oriental Pasha, his house was always so full of people that he had quite often to sell them to keep the coffers flowing.

He left one ceramic vase with us. It still stands on a pedestal in a corner, converted now into a lamp stand, its deep blue and copper red tones changing colour with the reflection of the light. “It’s a very rare vase from China. Don’t ever sell it,” he advised, though he himself regularly sold many of his most cherished possessions.

When we lived in Geneva, he happened to be in Berne. His boss at that time was a dog-lover of epic proportions, so every evening as we stood beside him and listened, he talked to the dog, a large Alsatian, who had been left behind in his care, in Urdu, on the telephone.

On another occasion, he told us how the dog had finally died and he was “Chief Mourner” the had conducted the funeral honours. “It was a very touching occasion. I was so moved, I jumped into the open grave and recited some prayers over the dog’s body that I held in my own arms, before laying him into the earth,” he told us. Since he was laughing so much at the memory, we never knew whether any of this was true. Or whether like all the stories he had told us in the past, they were the stuff of the legendary quality that he wove around himself.

“He never mentioned his life with the INA, let alone the story that he had been the one to coin the greeting, “Jai Hind!” remarks my Mother, “Though it sounds very typical of him. He was a free spirit.”

Much later when one of us was passing through Denmark, where he was the Ambassador, we enjoyed the full force of his hospitality. He drove to the airport himself and though when we reached his house, it seemed to be so full of guests that evening, he had to find a room for us, right up in the attic. But as ever it was a fabulous evening. The dinner when it arrived was as full and rich as one of the tables from the days of the old Hyderabad style hospitality. He always managed to have as a hostess, one of his beautiful nieces from Hyderabad, who would quietly attend to the guests and see that no one was without food and drink.

When it was over, he insisted that we should go and enjoy the “Tivoli Gardens,” that was the star attraction of Copenhagen. As we looked at the giant Ferris wheels and the nightly display of fireworks exploding over the skyline of the City, Uncle Safrani had become like Barnum, a grand ring-master presiding over the “Greatest Show on Earth”.

And then we did not see him again.

We had heard that he had returned to his family home after retirement and become a gentleman farmer.

This is my final memory of him.

On a visit to a silk weaving unit on the outskirts of Hyderabad I found that someone had started a small farm, and on it a school for the children of the nearby village.

The owner, who had died some time back had created an enchanted garden of fruit trees. The fields next door were covered with jasmine bushes, dotted with fat creamy jasmine buds, that the children from the school came to harvest in the early morning. The air was filled with their fragrance as all over the field the butterflies were busy doing their own kind of harvesting.

One of this man’s nieces, a really beautiful woman even in her later age, was running a weaving centre. She was pre-occupied in reviving some of the old Hyderabadi silk and cotton weaving traditions and did not have much time to talk. On her table was a photograph of a familiar face, the same moustache, the full lips ready to form themselves into a kiss, the all embracing smile, the jaunty glint in the eye.

“Safrani!” I exclaimed.

The beautiful niece, still glowing in her old age looked at the picture. “My Uncle” she said, quietly.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Young World / by Geeta Doctor / Online Edition / Saturday – March 23rd, 2002