Kolkata, WEST BENGAL :

Kolkata / Lucknow :

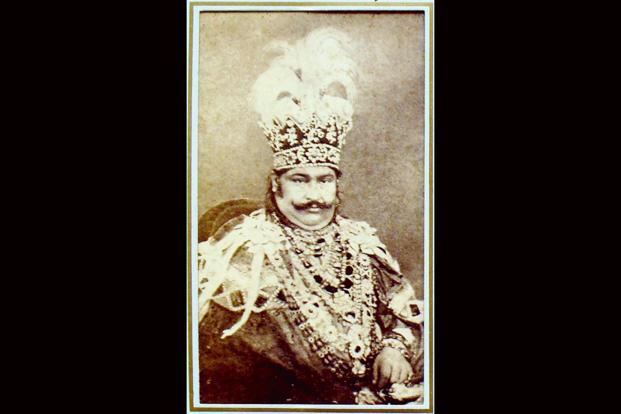

Kaukub Quder Sajjad Ali Meerza, the great-grandson of Awadh’s last monarch, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, and grandson of Nawab Birjis Quder, died of Covid-19 in Kolkata on Sunday afternoon, aged 87.

Considered an authority on Wajid Ali Shah’s literary and cultural contributions, he is survived by his wife, two sons and four daughters.

Meerza may be buried on Monday at the royal burial ground(Gulshanabad Imambara), about a kilometre from the Sibtainabad Imambarah in Metiabruz, where Wajid Ali Shah rests.

A popular figure in the billiards and snooker fraternity of the country, Quder had graduated with honours in economics from St Xavier’s College in the same batch as Amartya Sen. He studied political science and then a three-year law course.

Subsequently, he studied Urdu at CU, won a silver medal in 1962 and also earned a UGC Junior Fellowship for research on the “Literary & Cultural Contributions of Wajid Ali Shah” in the department of Urdu at Aligarh Muslim University. In 1967, he joined the department as a lecturer and earned a doctorate for his thesis.

Kaukub Quder Sajjad Ali Meerza’s daughter, Talat Fatima, is now translating his book from Urdu to English. “His research was extremely rich. This book, published in the late 70s, has a compilation of some 42 works of Wajid Ali Shah. Some of them are in Persian,” she said, adding that her father preferred to be addressed as “Dr Kaukub Quder Sajjad Ali Meerza” instead of using the title of a prince.

It was his academic interest in his forefather that had also got Satyajit Ray to get in touch with him during the making of “Shatranj ke Khilari”.

On Ray’s birth anniversary this year, his daughter, Manzilat , had tweeted: “There are a couple of letters that were exchanged between Bawa [her father] and Satyajit Ray during the making of Shatranj Ke Khilari.” On Sunday, she spoke about how Ray had even visited their 11 Marsden Street residence that is popularly known as ‘House of Awadh’. “Ray could have gone to anyone else for information. But he chose to get in touch with my father. In fact, he had made many attempts to meet my father but the meeting never happened. Hence, it was through correspondence that he got the information regarding Wajid Ali Shah. I feel Ray had portrayed Wajid Ali Shah in the right light. Many often claim that Wajid Ali Shah had been exiled, but that isn’t true. He had left the kingdom of his own volition. I believe my father’s information helped him give authentic information about Wajid Ali Shah,” she said.

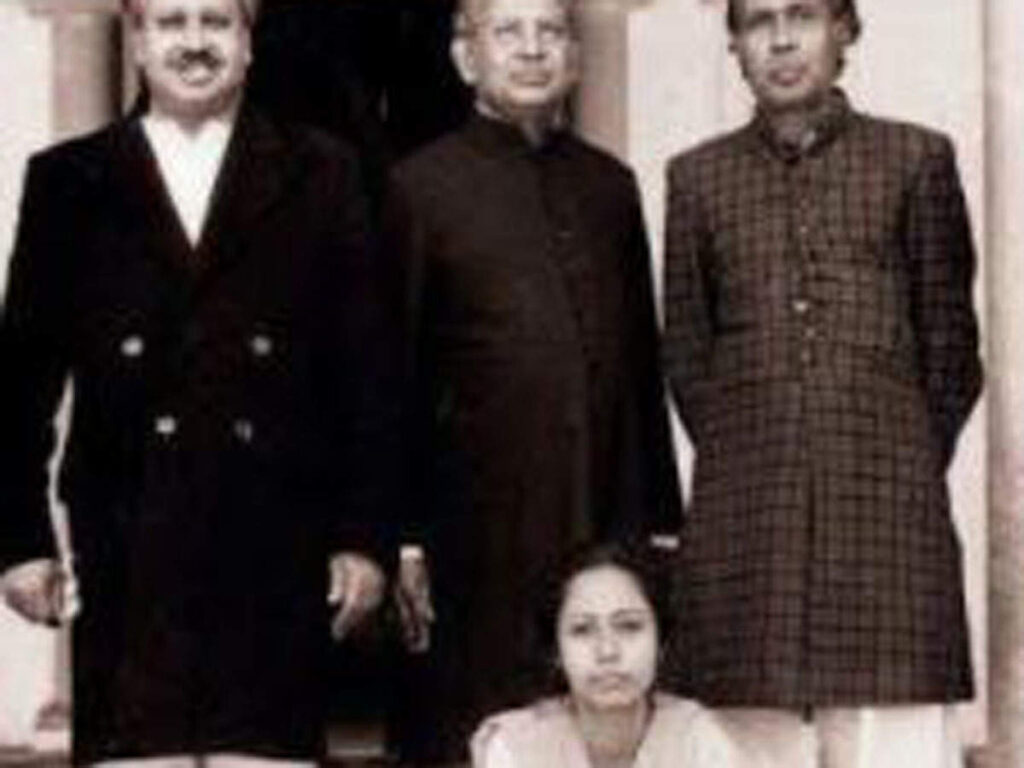

Quder was also a great connoisseur of food. A big photograph of him along with his two brothers hangs in the rooftop restaurant opened by his daughter. “He was happy when he saw how, in my capacity, I was upholding the family name. Awadhi food was already losing its identity. He was happy I was making the effort to popularize that food,” Manzilat said.

Incidentally, he was the chief referee of first World Snooker Championship held at the Great Eastern Hotel in Kolkata in 1963-64. He had remained the chief referee of the National Billiards & Snooker Championship till it left the Palm Court of the Great Eastern Hotel in the 70s .

“It was my father who coached me to play snooker and billiards. I became the first woman participant from India to play the games at the national level,” said Manzilat.

The rolling trophy of the IBSF World Snooker Championship, the MM Baig Trophy, was designed by him. In the 70s, he had also brought out a pioneering Billiards magazine, “The Baulkline”.

According to his son, Irfan Ali Mirza, “He was the founder-secretary of The Billiards & Snooker Federation of India, The West Bengal Billiards Association and The Uttar Pradesh Billiards & Snooker Association.

Sudipta Mitra, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Peerless Hospital and a student of Meerza, describes his mentor’s demise as a “huge loss”. “A part of our cultural history is lost with his demise. He came with pneumonia and was admitted to the ICCU. Unfortunately, he passed away today afternoon due to Covid pneumonia. Jawaharlal Nehru had initiated the idea of the government of India bearing the expense of his education. He was my research guide while writing the book titled ‘Pearl by the River: Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s Kingdom in Exile’,” Mitra said

The Peerless Hospital CEO, said according to his research, he was “the last royal pension holder”. “In 1892, the British government had created a royal pension book where only the lineage of Birjish and his wife, Mahtab Ara Begum, who was the granddaughter of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal Emperor of India, was recognized.

Birjish, who was the only son of Wajid Ali Shah and Begum Hazrat Mahal, was the eldest surviving son of Wajid Ali Shah when the latter died in 1887. That is why this lineage has been recognized for royal pension,” Mitra said.

source: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com / The Times of India / Home> News> City News> Kolkata / by Priyanka Dasgupta and Yusra Husain / TNN / September 14th, 2020