WEST BENGAL:

In a conversation with FII, Moumita Alam discusses how she began writing poetry, and what it is like being a Muslim woman in a Hindu majoritarian state and how the voices of certain minorities have been silenced throughout Indian history.

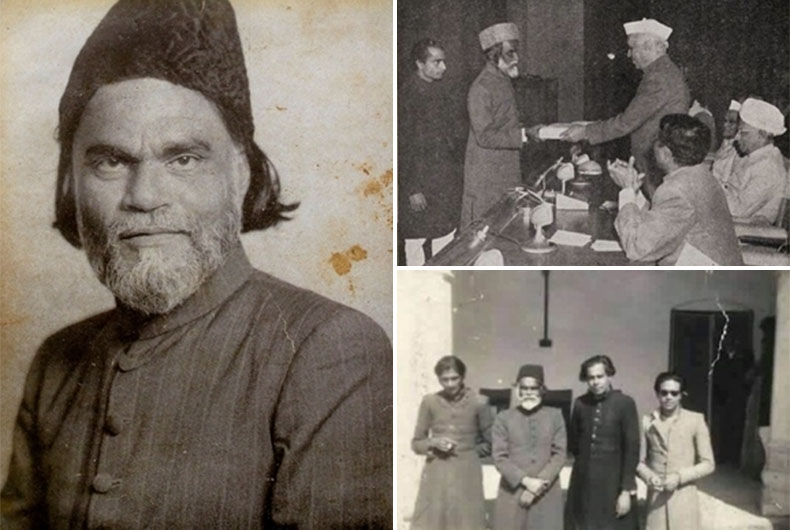

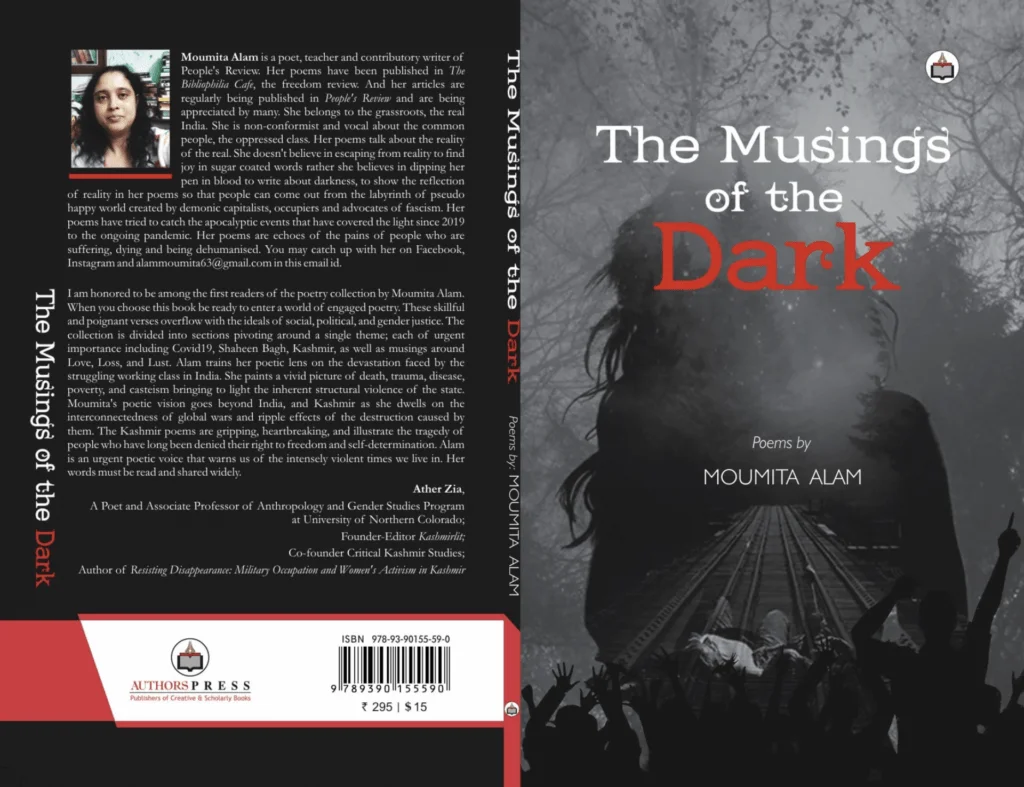

Moumita Alam is a teacher based in West Bengal whose political poetry, over the past few years, has gained incredible popularity in South Asia due to its powerful messages and themes. As a Muslim woman, through her poems, essays and opinion pieces, she attempts to bring out the atrocities faced by the women of her community alongside critiquing the larger issue of rising Islamophobia in India. Her first and only book, The Musings of the Dark was published in 2020.

In a conversation with FII, Moumita Alam discusses how she began writing poetry, what it is like being a Muslim woman in a Hindu majoritarian state and how the voices of certain minorities have been silenced throughout Indian history, particularly in West Bengal ever since the 1947 partition.

FII: You have, over the past few years, used your poetry to both raise awareness about and protest against the Islamophobia propagated by the ring wing in our country. Would you like to shed some light on what your writing journey has been like?

Moumita: I began my poetic journey after 2019. In 2019, on the 5th of August, the abrogation of Article 370 happened. I had a friend who lived in Kashmir, so I lost connection with him. He was an aspiring advocate who would regularly speak with me. I, as a teacher and a single mother, would share my life journey with him in return. But in 2019, when I could no longer talk to him, a sense of guilt began haunting me — how could a land become a prison where the people couldn’t even make a phone call to the ones in the outside world?

At some point in time, I thought of writing a letter to him, but receiving a letter from here could land him in trouble. He was much younger than me but was my only friend who would listen to my feelings, my happiness, my sorrows. So, I began writing.

I am against the use of the term “migrant labourers,” because India is our own country, so how can its citizens be called migrants? — to come on the grounds and walk for miles and miles to reach their homes.

Moumita Alam

That same year, in December 2019, the Anti-CAA-NRC movement started and we suddenly became aware of our religious identities. Everyone around me would ask me, “Are you legal? Are you a Bangladeshi?” But, believe me, I was born and raised in West Bengal. I have never even seen or visited Bangladesh. Every Muslim I know — whether practising or non-practising — was being asked this question. So, after my Kashmiri friend, I lost my other friends too because their questions would hurt me. I wrote about those feelings too.

And then again in March 2020, we saw how the unplanned lockdown forced the workers of the unorganised sector — I am against the use of the term “migrant labourers,” because India is our own country, so how can its citizens be called migrants? — to come on the grounds and walk for miles and miles to reach their homes. I could not sleep for days because I live in a village and many of my relatives and fellow villagers used to work in Kerala and Delhi as labourers. So, I also started to write poems about their plights and sufferings.

One of my friends asked me to send my poems for publication, which had never crossed my mind because I stay far away from Delhi and its so-called “English literary circle.” But I still emailed a publisher who agreed to publish and then, my first and only book, The Musings of the Dark came out in August 2020.

FII: Since your poems usually focus on the theme of gendered Islamophobia or the issues that Muslim women face in our country, what is it like being a Muslim woman in a country governed by the right-wing?

Moumita: In 2021, I got to know that a few right-wing fanatics had created an app to sell Muslim women and had named it ‘Bulli Bai.’ I was so disturbed after reading the news about this because this is such a heinous thing to do — how can anyone do this in a democratic country like India?

So, I wrote this poem, “I am a Muslim woman and I am not for sale.” This poem was translated into many languages — in Telugu, Assamese, Bengali, Tamil, Kannada, and others — and was also published on various platforms.

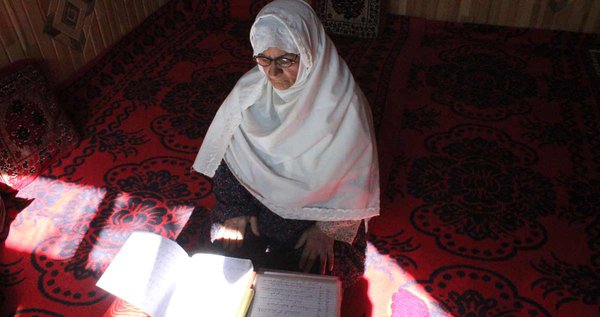

If you follow the news, you would know that in 2022, hijab was banned in schools across the country. Even if I don’t wear hijab, you can’t ban other women who do from getting an education. As women, we are a minority in many ways — first, as Muslims in this country and then, because of our gender. We have to bargain our choices and sometimes, we have to compromise in front of our families by saying, “I will work hard, I will wear a hijab, please let me go to the doors of education.”

When a man is interpreting religious scriptures for you, he will — whether consciously or unconsciously — view religion through a patriarchal lens. They might not allow us to gain an understanding of the equal rights that Islam gives to Muslim women.

Moumita Alam

After becoming independent, I, as a Muslim woman, can decide for myself whether or not I wish to wear a hijab. But, you can’t put a blanket ban on hijab like that.

While I do write poems on the rising Islamophobia in our country, I also write about the oppression we Muslim women face within our own communities. Look, our society is based on patriarchal notions which means that even a lot of religious preachers are men. When a man is interpreting religious scriptures for you, he will — whether consciously or unconsciously — view religion through a patriarchal lens. They might not allow us to gain an understanding of the equal rights that Islam gives to Muslim women.

FII: Have you ever faced censorship for having political themes and highlighting the various injustices particularly on the basis of religion, in your work?

Moumita: Thankfully, we still have some platforms that provide a space to people like me where we can raise our voices. I am thankful to the Editor of LiveWire, who recently resigned. She was an immense pillar of support for me because she never censored my work — she either accepted it or denied it from being published, but never censored it. Even the Editor of Outlook is brilliant that way.

Sometimes, however, my poems get rejected by other platforms because they say my work is too political, but I think we are living in a time during which one can’t be apolitical. If you are, then you are indirectly standing with people who are unleashing injustice towards minorities.

FII: As a poet who writes in both English and Bengali, you have often talked about how the voices of certain minorities have been neglected even within Bengali literature and poetry — an example of which can be the Marichjhapi massacre in 1979. Is there anything that you would like to discuss about the domination of certain elite classes and castes in Bengal?

Moumita: You might have noticed that for the non-Bengalis, West Bengal is equal to Kolkata — all of Bengal is just Kolkata for most people who aren’t from Bengal. This suggests a very Kolkata-centric attitude that most people have about Bengal. The literary world is, of course, not an exception — it’s so Kolkata-centric that people like me who are living in the margins find it almost impossible to reach the centre that is Kolkata.

Also, the Bengali literary world has been dominated by upper-class, upper-caste people for a very long time. So, they write about only those issues that they know about and that suit their narrative. Things are changing, some voices are getting spaces. However, we still have a long way to go. »

FII: When we usually talk about the India-Pakistan partition, the discussion inevitably gets centred around the division of what is present-day Punjab with little being said about how the refugees of Bengal, particularly the oppressed even among the displaced, were impacted. As someone who has written articles on this theme for both English and Bengali publications, can you tell us a little about your understanding of the same?

Moumita: Yes, I agree with you that the pains and sufferings of the Bengali refugees haven’t found expression in the so-called mainstream literature, particularly English literature. When I’m talking about “Bengali,” I mean both Hindus and Muslims. The plights of the oppressed class like the Namasudra community who were forced to migrate to West Bengal from the then East Pakistan is missing from the literary narrative. Equally, even the traumas and voices of the Muslims who stayed back while the other members migrated to East Pakistan are missing from the literary imagination.

Most importantly, after partition, no political establishment tried to heal the wounds of the refugees. We all understand how the various European governments attempted to heal the wounds of the holocaust survivors after the second world war, but the same did not happen in India, even though the partition is often compared to the Holocaust.

Instead, every political party tried to gain political mileage from the religious fault lines. If I am not mistaken, nothing much has yet been written about internal migration. How many partition museums do we have?

FII: Every time your poems about the Babri Masjid demolition or about Kashmir get published, there are a lot of derogatory things that are often said by right-wing people— such as a lot of Kashmiri Pandits who end up claiming that their own stories need to be heard over yours. Since you have been doing what you believe in for so many years, is there any advice that you’d like to give to the young girls of our country about how they can voice their thoughts fearlessly even when they are intimidated?

Moumita: We are living in a critical juncture of time. As witnesses of this time, we can’t let the fascists win. How are they winning? They are winning through their narrative — a narrative of hatred towards minorities, towards women. We have to tell our own stories, we have to counter their narrative by our narrative.

So, here is my message for all women:

I wish you,

Oh women,

A savage fury

To throw all the

Dos and don’ts

Under a ravaging bus.

And begin from the beginning

All-new, all equal.»

FII: You write and publish your creative works and political thoughts as a freelancer, which means there is very little for you to gain from it as a poet. If anything, your poems and articles have mostly just led people to threaten you. What is it that motivates you to continue writing even when things don’t entirely work in your favour?

Moumita: Silence is not an option. The hatred that engulfed my friends still haunts me. I am a villager and I know how common people are suffering every day. The silence of the intellectual people saddens me. I want to jolt them, wake them up from their hibernation.

I am a villager and I know how common people are suffering every day. The silence of the intellectual people saddens me. I want to jolt them, wake them up from their hibernation.

Moumita Alam

You know, potatoes are the only profitable crop in my village. This year, the poor farmers incurred a heavy loss and couldn’t repay the loans they had to take from private microfinance companies at heavy interest rates. I asked a very old farmer how they plan to survive after this loss? And he replied, “Next year we will get some profit.” I was just amazed at his belief and relentlessness. I believe we can bring a change. We have to hope because we don’t have any other option.

The interview has been paraphrased and condensed for clarity.

source: http://www.feminisminindia.com / Feminism In India / Home> Interview / by Upasana Dandano / June 09th, 2023