Basti Nizamuddin, NEW DELHI :

The unmarked resting place of Miza Ghalib’s wife deserves an epitaph

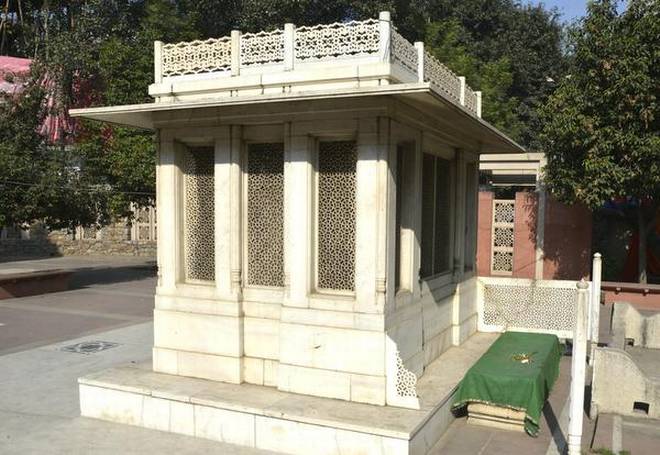

The grave of Mirza Ghalib’s wife, Umrao Begum, in Basti Nizamuddin, just at the side of her husband’s tomb, lacks an epitaph, probably because nobody tried to inscribe one on it in 1955 (when the poet’s memorial was built) or because she preferred anonymity as per the strictest tenets of Islam. Even so she deserves one for posterity’s sake. Umrao Begum was a pre-teenager when she married Ghalib, who himself was just 13 at that time, and the two shared conjugal bliss for nearly 57 years.

Umrao Begum was a kinswoman of the Nawab of Loharu, an erstwhile State now merged with Rajasthan, and her cousin was Bunyadi Begum, Ghalib’s sister-in-law. The begum, who was the Nawab’s sister, gave her haveli in Gali Mir Qasim Jan to Ghalib when he was in need of accommodation.

Umrao Begum bore seven children, all of whom died in infancy, leaving her and the poet heart-broken all their lives. Even the nephew, Nawab Zainul-abadin Khan Arif, whom they adopted, died young at the age of 18, though he had made his mark in Urdu poetry by then.

Strict lady

Umrao Begum was a strict Muslim lady, whereas Ghalib was not at all orthodox. After the First War of Independence of 1857, the poet was accosted by an English officer who asked him if he was a Muslim (as most members of the community were suspects in the eyes of the British). Ghalib replied “Half”. The officer sought an explanation to which Ghalib said that though he drank, he did not eat pork. The amused officer, marvelling at his wit, left him in peace.

Once Ghalib came home with a man carrying a basket full of wine bottles, bought with his first pay. Umrao Begum asked him why he had spent all the money on liquor, to which his reply was that God had promised to feed everyone but had not made any provision for drink, for which one had to make one’s own arrangements.

At another time he entered the courtyard of the house with his shoes on his head. To the Begum’s query, he replied that as she had made the whole haveli a masjid by her piety he had no other option. Umrao Begum died in 1870, a year after Ghalib, when Mahatma Gandhi was only a few months old and was buried according to her wish next to the poet.

Unfortunately, the Ghalib memorial built 85 years later became a barrier between the two graves, both of which should have come within its ambit. But it’s never too late to make amends for an oversight — if need be with Government help.

Her love for Ghalib was intense or he wouldn’t have been able to lead the carefree life he did. She was the one who took care of the house despite the poet’s love for gambling and dance girls, one of whom took undue advantage of him. Despite mischievous gossip by mohalla women, Umrao Begum was unruffled because she was convinced of her husband’s goodness of heart. Even when there was paucity of funds, she managed to see it to that Ghalib and nephew Arif got three square meals a day.

After the death of her children, she was the one who comforted her Mian Nausha so that the misfortune did not affect his mental equilibrium, without which his wit would not have continued to flow like the sparkling Thames.

Facing the music

Ghalib spent most of his time outside the haveli, except when he was writing poetry, having his meals or resting. So it was Umrao Begum who faced the creditors as she was the one who responded to the knock on the door in the absence of a regular maid. When the fat Kotwal of Delhi tried to bully Ghalib, as he disliked the poet because of their love for the same tawwaif and considered him a potential rival (as he always stole the limelight at the kotha), his wife was the one who confronted the Kotwal’s importunate minions at the haveli’s entrance and sent them away with the proverbial flea in the ear.

When Arif was grooming Alexander Heatherley “Azad” as a shair, despite his Anglo-Indian antecedents, Umrao Begum took it upon herself to see to it that they were not disturbed and had some refreshments too during the long hours of coaching. Ghalib who had earlier imbibed the love for shairi in Arif, also fawned on him and when he died an untimely death, poured out his grief in a heartfelt elegy (quoted from memory) that is among his best poems: “Jatey huey kehtey ho qayamat ko milenge kya khoob, qayamat ka goya din hai koi aur!” (While departing you say will meet on the Last Day of Judgement, what an excuse on the pretext of a reunion on a vague day in Eternity).

Reading the elegy Umrao Begum burst into tears and told Ghalib not to rub salt into her raw wounds, according to Arif’s pupil, Alexander Heatherley’s descendant, George Heatherley who died in Perth a few years ago. Umrao Begum’s grave close to Ghalib’s is testimony enough, if one were needed indeed, of the emotional link between the two. Then why deny her the courtesy of an epitaph to seal the bond for the benefit of future generations? No matter how distant may be Arif’s final place of repose.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> Down Memory Lane – History & Culture / by R.V. Smith / November 27th, 2017