Surat , GUJARAT / Bombay (now Mumbai) MAHARASHTRA / London, ENGLAND :

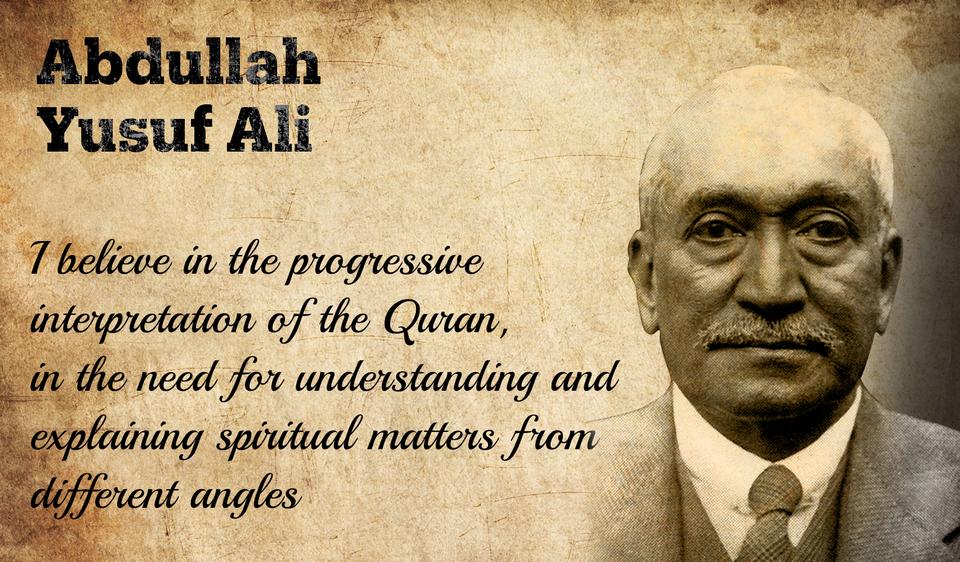

Abdullah Yusuf Ali wrote perhaps the most famous translation of the Quran but he also supported the British against the Ottomans and died a lonely man.

On a frigid December morning in 1953, a policeman found a half-conscious old man slumped on a street bench in the Westminster area of London. He was in a delirious state and died a day later on December 10. Ali

That man was Abdullah Yusuf Ali, the famous 20th-century translator of the Quran. He died alone, homeless, and with no one by his side. When the news reached Pakistan’s embassy in London, it dispatched someone to pay for his last rites.

“It pains me to think that so able and eminent a gentleman should have met with so pathetic an end,” Mirza Abul Hassan Ispahani, Pakistan’s High Commissioner in London, wrote in a letter to his prime minister two days later.

Generations of Muslims in English-speaking countries have grown up reading Yusuf Ali’s interpretation of the Quran. More than 200 editions of it have been published so far, making it perhaps the most read commentary in any non-Arabic language.

“Ask any English-speaking Muslim what translation and commentary of the Quran they originally studied, and the chances are that it was the one by Abdullah Yusuf Ali,” writes a commentator.

Yusuf Ali’s work and affiliations solidify his place as a giant of his time. He was one of the most senior Muslim civil servants during the British Raj, rubbed shoulders with the likes of Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the Aga Khan, inaugurated the first mosque in Canada, represented India at the Paris Peace Talks in 1919, was a trustee of London’s oldest mosque, and a known educationist. He was also a prolific writer on Islam.

But how did a prominent Muslim like him meet such a terrible end? Why was he forgotten so quickly?

A child of his time

In 1915, during World War I, the British faced a dilemma. Nearly half a million soldiers were Muslims from the Indian Subcontinent — modern-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh — which was then under colonial rule. Some refused to fight the Turkish Ottoman soldiers who had joined the war against the allied army.

A mutiny broke out in November of that year in Singapore where Indian Muslim soldiers turned their guns on officers and took control of the island. The uprising was quickly crushed and 70 Muslim men were lined up against a wall and executed.

The events shook British officials. Many Muslims considered the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed Reshad as their Caliph. Their personal affinity and strong connection led to the Khilafat Movement in India that called for boycotting the British.

Abdullah Yusuf Ali thought otherwise.

“Fight ye glorious soldiers, Gurkha, Sikh or Muslim, Rajput or Brahman!” he said in a November 1914 speech at a London event in front of top British military officials. “You have comrades in the British army whose fellowship and lead are a priceless possession to you.”

In his talks and articles throughout the war, he urged fellow Muslims to side with the British, at times doing it so effusively that his rhetoric appeared jingoistic.

“The Ottoman Caliph announces Jihad against the British and what does Yusuf Ali do? He goes around European countries asking Muslims to fight for the British,” Humayun Ansari, a professor of Islam at the University of London, told TRT World.

“He was consistently loyal to the British and considered the British Empire to be a blessing. In his understanding of Islam he was very liberal. He wanted a reconciliation between the Muslim and Western philosophy.”

Yusuf Ali was born in 1871 in Surat, western India, during a period of great introspection for the Muslims of India as their rule over the region for centuries came to an end and they were at the mercy of the English and a more politically organised Hindu majority.

Among the Muslims there was a realisation that they would have to study English, attain a modern education and learn British ways to get government jobs and regain their lost social status.

Yusuf Ali, who came from a middle-class family, proved to be an exceptional student throughout his school years and after matriculating from a missionary school, he won a scholarship to study at Cambridge University in London. The scholarship was given to only nine Indian students each year.

“We have to look at him in the context of his times. That was a generation when the British claimed superiority over the natives. And then you have somebody who can emerge and beat them at their own game,” says Jamil Sherif, who wrote Yusuf Ali’s biography titled Searching for Solace.

“Yusuf Ali’s approach was to show through his writing that Islam had made major contributions through the ages. But I think his compromise was that he saw religion mainly in spiritual terms and he saw socio-political dimensions of Islam as not really relevant in the days of empire,” he told TRT World.

At Cambridge, Yusuf Ali excelled in English composition, Arabic and other subjects. He also cleared the intensely competitive exam for the elite Indian Civil Service (ICS). In subsequent years, he rose to become perhaps the highest-ranking Muslim civil servant in India when he worked under Cabinet’s member of finance.

He was a devout Muslim, making sure he offered daily prayers, attended religious congregations and led prayers at the Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking, a town near London.

At the same time, he was against political Islam and insisted that Muslims could do better under British rule and that they should focus on educating themselves as opposed to agitating for independence.

Over the years, he remained affiliated with different institutions and also served as the principal of Lahore’s Islamia College – he was invited to take the position by the venerated poet Allama Muhammad Iqbal.

But behind the veneer of his intellect, busy schedule and scholarly importance, he was a man suffering from internal conflicts.

When the east meets west

Yusuf Ali was a troubled man. He married twice and both relationships ended bitterly.

In 1900, just a few years into his role as a civil servant, he married Teresa Mary Shalders, in a ceremony at the St. Peter’s Church in England.

“It was a bold and uninhibited act by the young couple, who may have looked at the dawn of the new century and thought everything possible – including the harmony of races, religions, and continents,” Sherif, who uses M.A. Sherif as his pen name, writes in his book.

But any hope of making a statement with this marriage of two different cultures faded in a few short years. They had four kids over the years but Yusuf Ali spent most of this time in India as a government officer while Shalders, who was in England, fell in love with another man.

Their divorce in 1911 was particularly painful for Yusuf Ali and he might have hinted at that period in the preface of his Quranic commentary when he wrote: “A man’s life is subject to inner storms…which nearly unseated my reason and made life meaningless.”

He won custody of their children but became estranged from them over time.

“These children by their continued ill-will towards me have alienated my affection for them, so much that I confer no benefit on them by this will,” Yusuf Ali later wrote in his will.

As an ICS officer, he rose swiftly from an assistant magistrate to more important positions, and the British government increasingly relied on him as its key propagandist.

Yusuf Ali was not entirely oblivious to the systematic discrimination that Muslims faced under British rule.

“He wrote about how Britain was using Indian revenue in the Great War. That’s a very subtle way of criticism. He also made references to discrimination suffered [by locals] on the basis of colour,” says Sherif.

In the early 1920s, Yusuf Ali married Gertrude Anne Mawbey, who he liked to call Masuma (innocent). That marriage didn’t work out either.

It was during this personal crisis that Ali began the monumental work of writing an English translation of the Quran, often working on solitary ocean liner journeys which he took at the behest of the British government.

“Yusuf Ali’s bond with the Quran was forged in these times of anguish when searching for solace,” writes Sherif.

Prominent scholars such as Marmaduke Picktall and others had already done a lot to introduce the West to Islam’s holiest book but Yusuf Ali did it with humility and open-mindedness which set his work apart.

“His interpretation is very balanced. It doesn’t force you to any particular corner, it can be read by all the schools of thought. It’s a very broadminded, compassionate approach to studying religion,” Sherif tells TRT World.

Yusuf Ali was a Dawoodi Bohra, a strain of Shia Islam, but he garnered enough respect across the spectrum to lead congregations at Sunni mosques.

“In his translation of the Quran, published between 1934 and 1937, Yusuf Ali expounded the spiritual side of Islam more than its worldly view,” writes A R Kidwai, a prominent researcher.

His excellent command over the English language lends a poetic touch to the thousands of footnotes and he didn’t shy away from using English poets such as Longfellow and Milton to explain the word of God.

Besides dealing with his matrimonial failures, he had a hard time coming to terms with what happened to Arab Muslims after World War I.

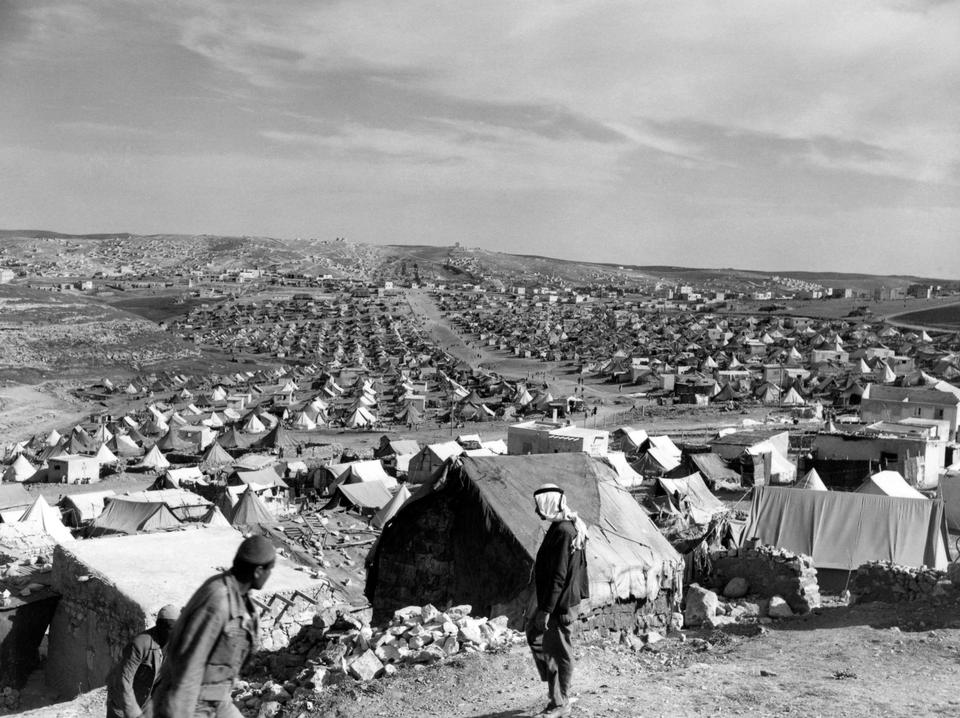

“Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not criticise the League of Nations when it dismembered the Ottoman empire,” says Sherif. “But what really shook him was the proposal to partition Palestine.”

For someone groomed to believe that the English people were true to their word, the haphazard division of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of Israel was unsettling for Yusuf Ali.

In 1937 he attended many meetings and conferences fighting the case of Palestinians and warned Western powers about creation of a Jewish state on Muslim land.

“One way alone can bring thee peace:

That ancient rights be not suppressed,

That aliens from encroachments cease,

And Quds be given its rightful rest,” he wrote in the poem Palestine published in January 1938.

However, Palestine’s tragedy wasn’t enough to deter his loyalty to the British as he travelled to India at the urging of England’s Ministry of Information to rally Muslim support after it declared war on Germany in 1939.

In Delhi, he met Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan and spoke to students about the need for India’s support for the British. That was a time of turmoil in India as both Muslims and Hindus had begun rallying for independence.

Upon his return, he wrote articles and gave speeches, asking Indians to unite in defence of the empire and drop their demand for political reforms. But his appearance as an important player in international events quickly faded after the war ended in 1944.

We might never know what broke him in the end. But as the British pulled out of the subcontinent in the days of its waning global status, so did Yusuf Ali slowly recede from the newspapers, his powerful friends no longer found a use for him.

Yusuf Ali spent his last years living in the National Liberal Club on a monthly pension that he received against his government job.

“How did the British treat him? There’s certainly a question mark there. They didn’t recognise his contribution as much as he probably expected,” says Humayun Ansari.

His powerful friends in the Muslim community including Pakistan’s then ambassador Ispahani had also lost track of Ali’s whereabouts, not bothering to check on him.

“That is an indictment of the Muslim society that we were not able to honour and care for someone of his stature,” says Jamil Sherif.