Kolkata, WEST BENGAL :

In his autobiography, Hamid Ansari, Vice-President for two terms, brings to the fore the predicament of Indian Muslims, who still live in the shadow of Partition

The Indian republic has had 13 vice-presidents since 1952 and only two, Dr. S. Radhakrishnan and Hamid Ansari, got two terms in office. Therefore, it would be natural and tempting to focus on Ansari’s vice-presidential years, but it needs to be kept in mind that the post of Vice-President is essentially an inconsequential office in terms of power and authority; to the extent, the Vice-President also doubles up as the chairman of the Rajya Sabha does allow the incumbent some wiggle room, but that too can be misleading. Of the 13 men, only one, Bhairon Singh Shekhawat, had some political heft but he too was to discover that parliamentary conventions and politicians’ conveniences ensure that a party man gets cordoned off from the power vortex.

Civility and grace

The other hat Ansari wore for many years was that of an Indian diplomat. He was a competent, loyal foot-soldier and at his joyful best when crossing swords with Pakistani counterparts at global forums. It would perhaps be most rewarding to read the book as the reflections of a nationalist Indian Muslim.

Ansari acquaints readers with a different generation that valued civility, grace, erudition, and took pride in its love for scholarship, language and poetry.

He anchors himself firmly in the nationalist milieu; early in the book we are informed that his father spurned Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s invitation, on the eve of August 14, 1947, to all senior Muslim officers to proceed to Pakistan. The senior Ansari expressed his inability “to change my country.” The Ansari family was only one of the two at the senior level to stay back in India. A choice was made: India was home.

Modernist at heart

This confidence in the new, free India was justified when Ansari made it to the elite Indian Foreign Service. A meritocracy was at work. The new arrangements were fair, in letter and spirit, and being a Muslim attracted no discrimination nor endowed any advantage.

He locates himself unapologetically in the modernist milieu. He fell for — then married — a young “cigarette-smoking and sherry-sipping” woman. He did not defer to traditionalists and conservatives. There is not an obscurantist bone in this doubly cosmopolitan man, who is just as much at ease in any western environs as he is well-versed in the civilisational richness of the global Islamic world.

Consequently, he never allowed himself to get inveigled in the intrigues and pettiness that soon came to define the Muslim political crowd, especially when Muslim leaders and the masses got entangled with the exigencies of electoral politics. Nor was he unobservant of the unhealthy tendencies creeping upon Muslim society and its institutions.

For precisely this reason his reflections on the state of the Indian Muslims command our attention and respect.

Ansari acknowledges that from the very beginning the Indian Muslims have lived under “a shadow of physical and psychological insecurity” because they were made “to carry, unfairly, the burden of political events and compromises that resulted from the Partition.” And, as the Sachar Committee Report would record, they remain on “the margins of structures of political, economic and social relevance.”

Islam and nationalism

Given our own constitutional commitments, Ansari wants to underline “the imperative to recognise pluralism and secularism as the normative principles of politics” along with “an unflinching adherence to principles of equality and equal treatment.”

He is not reticent about reflecting on the unresolved and unsettled equation between Islam and nationalism. A ‘successful synthesis of Islam and nationalism’ is very much feasible, because, as he argues, invoking Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, “…nationality is not synonymous with religious community since the two are in the shape of concentric circles that do not collide…”

Nor, for him, is there any fundamental incompatibility between Islam and democracy in the Asian Muslim world.

Yet, as he puts it, there is global dimension to the followers of Islam. The Muslim communities all over, including India, do subscribe “to an emotional bond of ‘Muslim-ness.’ The sentiment is amorphous as well as real; it is usually taken for granted but gets evoked at times of stress when protection physical or emotional, is perceived to be required.”

Ansari also tackles the ticklish issue of the majority-minorities syndrome in a democratic society. He argues for a need to move beyond ‘assimilation’ and ‘tolerance’. Both are inadequate from the minority perspective. While ‘tolerance’ does prohibit discrimination, it does not endorse diversity, and, therefore, leaves room for the problematic ‘other.’ And, of course, ‘assimilation’ simply boils down to absorption of the minority personality in the larger, majority crowd.

He comes across as a rare breed in these vulgar times. Instead of stridency, Ansari contextualises the many ‘accidents’ of his life with subtlety and sensitivity. With enormous reasonableness he enjoins us to ponder on the matrix of ‘accommodation’ and ‘acceptance’ intersecting with temptations of majoritarian politics. Perhaps it is this very gentleness in reminding us of our obligations to the social contract inherent in the Constitution that Prime Minister Narendra Modi mocked on the occasion of Hamid Ansari’s last day as Chairman of the Rajya Sabha. Neither leopard is willing to change his spots.

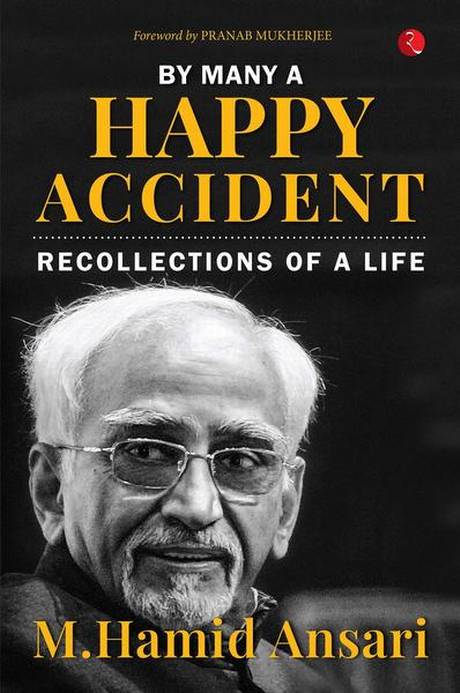

By Many a Happy Accident: Recollections of a Life; M. Hamid Ansari, Rupa, ₹595.

The reviewer is a senior journalist based in Delhi.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by Harish Khare / March 13th, 2021