Hyderabad, TELANGANA :

Abid Hassan, born in Hyderabad in 1912, hailed from a patriotic family.

Hyderabad :

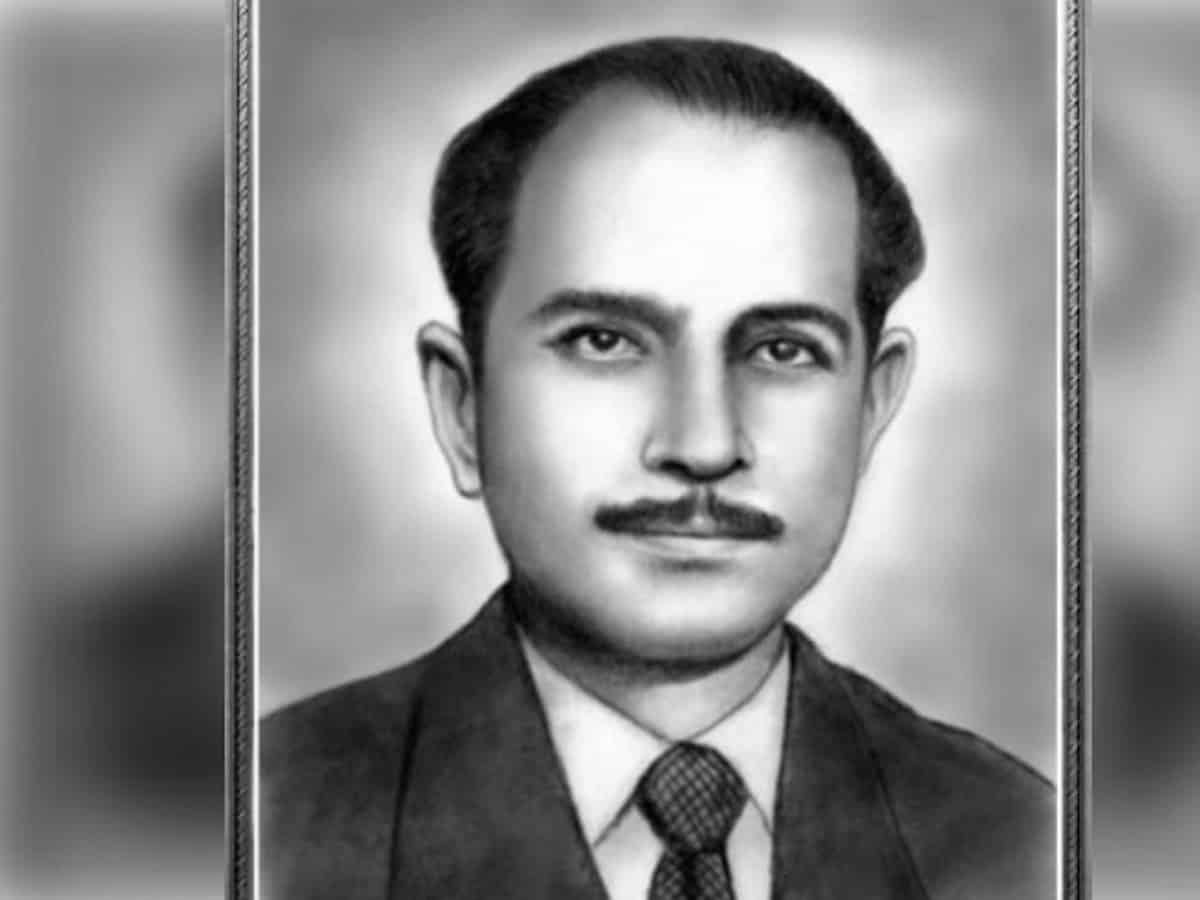

This is the story of Abid Hassan Safrani who, not many may know, was not just the trusted lieutenant of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, but the Hyderabadi who had coined the magical slogan JAI HIND.

I have had the privilege of translating into English the Telugu book on the life of Netaji Bose by the late Ch. Acharya at the behest of the Freedom Fighters Association.

The following are excerpts from the book. Kindly read on:

“JAI HIND ”. No slogan had ever cast a greater spell on the nation than this. It had welded the people of this country of diverse languages, cultures, and faiths during the freedom struggle and filled them with a strong sense of patriotism. It continues to do so even now.

The man who coined this stirring slogan was Major Abid Hassan Safrani of Hyderabad, a close aide of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose.

It was adopted as the national slogan at Free India Centre’s first meeting in Berlin in November 1941. Then, it became a popular form of address and greeting.

Safrani was with Bose when he undertook the death-defying undersea journey from Germany to the Far East. Safrani recalled how calm and composed was Bose when enemy ships rained bombs on the submarine. Unmindful, he dictated notes to Safrani on the future course of his action.

Sisir Kumar, the nephew of Bose, gave more details of the adventure in his book, ‘INA in India Today’.

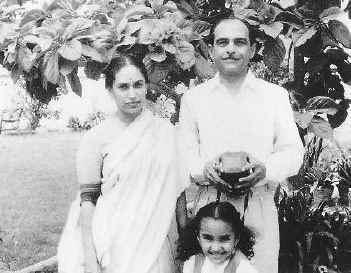

Abid Hassan, born in Hyderabad in 1912, hailed from a patriotic family. After graduating in engineering with distinction, he went to Berlin for higher studies.

Attracted by Bose’s freedom movement, he joined the Indian National Army. Recognising his leadership qualities, Bose gave Safrani ample scope to grow to his full potential.

Safrani could fluently speak several languages like English, German, French, Arabic, Persian, Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu, Telugu, and Punjabi. This enabled him to build excellent rapport with officers and men of the INA. Major Safrani headed the Gandhi Brigade in the INA. It consisted of men of exceptional courage and valour.

When they eventually surrendered to the British army at Imphal in North East India, top British officers could not help marvel at the bravery of Safrani and his men. He was imprisoned and put in solitary confinement with not even a window to allow light.

He mentioned this in a letter to his mother, Hassans had firm roots in nationalism. Abid’s father, Jaffer Hassan, was dean in Osmania University , and mother, Begum Amir Hassan, a staunch Gandhian. They inculcated patriotic feelings in their sons, Badrul Hassan and Abid Hassan, at a tender age.

All of them were very close to Mahatma Gandhi and used to visit his Sabarmati ashram. Fanatics threatened to kill them and throw their bodies into the Musi. Gandhi would send his secretary, Pyarelal, to railway station whenever the Hassans visited him. Badrul Hassan edited Gandhi’s “Young India” in 1925.

He remained a true Gandhian until his death in 1973. He wore khadi and led a spartan life in a small room.

Abid Hassan Safrani also imbibed these traits.

Begum Safrani was a unique personality who lived a full life(1870-1970). She gave away everything for the freedom of the country, including her paternal property. She was a close friend of Sarojini Naidu and was affectionately called ‘amma Jaan’ by Gandhi, Nehru, Netaji and Abul Kalam Azad.

“Abid Manzil”, their residence in Troop Bazaar, stands as mute testimony to the burning of foreign cloth in 1920 at the behest of Gandhi. In his book, Sisir Kumar Bose gave a graphic account of the escapades of Subhash Chandra Bose and Abid Hassan Safrani such as the submarine journey from Germany to Asia and the INA’s triumphal march through the forests of Imphal.

After the Second World War, Safrani was jailed for six years. Begum Amir Hassan, who did not expect anything in return for the services of the family, was much worried that her son might be sentenced to death in the Red Fort trial. Several INA men were shot dead for participating in the liberation movement. She met Gandhi, Nehru and Sarojini Naidu to plead for her son’s life.

Safrani got a last-minute reprieve after Prime Minister Nehru and Governor-General, Lord Mountbatten, intervened. Nehru had earlier visited a prison in Singapore where INA members were lodged. He spotted a man sitting aloof and asked if he was Safrani from Hyderabad . The man greeted him with “Jai Hind” and nodded ‘yes’.

After his release, an ailing Safrani returned to his “Dhoop Chaon” residence in Banjara Hills, Hyderabad and recuperated under the care of his loving mother and friends like Bankat Chandra, Elizabeth, and C.S. Vasu. He took up radio sales for a living, but with little success. He wrote a civil services examination and qualified for foreign service. He was personally interviewed by Jawaharlal Nehru .

He had served in Indian missions in a number of countries like Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, Senegal, Zambia, Ivory Coast. Safrani was Indian Ambassador to Iraq when Jordan King Hashmath-e-Faizal, was killed in an army coup in 1957. The government drew heavy flak in Parliament for his absence in Baghdad at the crucial movement. Nehru defended Safrani. Safrani loved agriculture and raised a horticultural farm in Golconda . It was his practice to visit Netaji’s hometown, Calcutta, in January every year carrying fruit grown on his farm.

That was his way of remembering his mentor, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. He used to recall with moist eyes those memorable years with Bose. He died in 1984 but immortalized himself with the soul-stirring slogan he coined: Jai Hind. It would keep the Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and others together for centuries and strengthen national integration. He was an ideal Shia and a noble Sufi saint.

Safrani memorial school in Golconda, run by his wife, Suraya, seeks to instill in the minds of young pupils the lofty ideals, values and principles dear to her husband.

Dasu Kesava Rao is a senior journalist who worked for The Hindu, among other newspapers

source: http://www.siasat.com / The Siasat Daily / Home> Featured News / by Safoora / January 26th, 2020