Allahabad, UTTAR PRADESH:

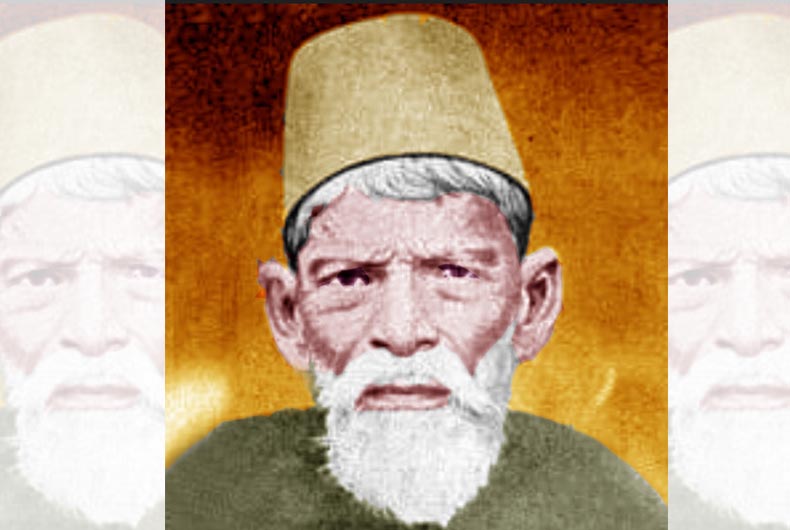

‘Akbar Allahabadi’ does not enjoy the place he deserves in the pantheon of Urdu poets.

His verse still figures in familiar poetry: “Ham aah bhi karte hain to ho jate hain badnaam..”, can be found embellishing a popular qawwali like “Jhoom barabar jhoom sharabi“, and is an optimum example of devastating use of wit and satire to deliver a social message in an era of “clash of civilisations”.

Yet, ‘Akbar Allahabadi’ does not enjoy the place he deserves in the pantheon of Urdu poets.

Called “Lisan-ul-Asr” (‘Voice of the Time’) in his heyday, he is not entirely unknown due to ghazals like “Duniya mein hoon, duniya ka talabgar nahi hoon…”, as rendered by the immortal K.L. Saigal, and “Hangama kyun barpa, thodi si jo pi li hain..”, performed by Ghulam Ali, with that line reflecting Descartes’ ‘cogito ergo sum’ (“… har saans ye kahti hai ham hai to Khuda bhi hai“), as well as many more couplets on a range of issues and themes.

Take “Falsafi ko bahs ke andar Khuda milta nahi/Dor ko suljha raha hai aur sira milta nahi“, or the rather sarcastic “Chorh ‘literature’ ko apni, ‘history’ ko bhool ja/Sheikh-o-masjid se ta’alluq tark kar ‘school’ ja/Char din ki zindagi hai koft se kya fayda/Kha ‘double-roti’, ‘clerki’ kar, khushi se phul ja”, or this “compliment” on lawyers: “Paida hua vakil to Shaitan ne kaha/Lo aaj ham bhi sahib-e-aulaad ho gaye“.

These can also serve to showcase the bundle of contradictions that Syed Akbar Hussain Rizvi ‘Akbar Allahabadi’ (1846-1921), a government servant, lawyer, and judge (rising to a district judge and in line in elevation to the high court before he resigned in 1903 on the grounds of ill-health) was in his life, thought, and poetry.

An early beneficiary of Western education himself (in the mid-1850s) and sending his son abroad to study, he deplored Indians flocking to it as a sign of their modernism, questioned and attacked colonial rule and its impact though he was part of its structure for most of his life and did admire the British, mocked lawyers though being one himself before rising to a high post in the judiciary, was deeply religious but made it one of the targets for his satire, and vouched for traditional culture but struck a new trend by using English words in Urdu poetry.

And then, he was a staunch supporter of Mahatma Gandhi, even writing the ‘Gandhi Nama’ in his support and while deeply religious, was never a fanatic and opposed all attempts to drive a wedge between Hindus and Muslims.

In an article on the poet, author and literary critic Shamsur Rehman Farooqui opines that it is possible that ‘Akbar’ was conscious of the contradiction, and “perhaps this sense of duality” made his “denunciatory voice so much more vehement, his disavowal of Western and British mores and systems so much more passionate.

Certainly, he knew that no one could really swim against the current, but the tragedy according to him was that those who swam with the current too were drowned”.

The general tenor has been to represent ‘Akbar’ as a reactionary holdout against progress and moderrnism, conservative in social mores and customs, especially on the issues of ‘parda’ and female education (“Be parda kal jo aai nazar chand bibiyan/’Akbar’ zameen mein ghairat-e-qaumi se gadh gaya/Pucha jo main ne aap ka parda voh kya huya/Kehne lage ki aql pe mardon ke padh gaya”) and then terming his unique style — satire, verging on sarcasm — as a “non-serious” and “dated” poetry.

But, this is rather unjustified. ‘Akbar’ was no reactionary but rather conscious of how the slavish and blind imitation of Western mores, habits, and education was going to sit only superficially on most Indians — with current times proving his case. He was not opposed to progress — but plumped for a more independent and reasoned adoption of attitudes and world-view of the modern, enlightened world, represented by the British.

And then, ‘Akbar’ plumped for Indians not to hanker for jobs in the colonial structure but instead, go in for business and trade so the country could rise. As he wrote: “Europe mein go hai jang ki quwwat badhi huyi/Lekin fuzun hai is se tijarat badhi huyi/Mumkin nahi laga sake do tope har jagah/Dekho magar ‘Pears’ ka hai ‘soap’ har jagah.

Let’s see more of his poetry, where he displays himself as a master wordsmith, be it being playfully romantic: “Jo kaha maine ki pyar aata hai mujh to tum par/Hans ke kehne laga aur aap ko aata kya hai”, mock heroic: “‘Akbar’ dabe nahi kisi Sultan ke fauj se/Lekin shaheed ho gaye biwi ke nauj se”, or trenchantly satirical: “Qadardano ki tabiyat ka ajab rang hain aaj/Bulbolon koi huyi hasrat ki woh ullu na huye”.

Then, take the master ‘deconstructions’ of the tropes of separation or union from the beloved: “Vasl ho ya firaq ho ‘Akbar’/Jagna raat bhar musibat hai”, or “Aai hogi kisi ko hijr mein maut/Mujh ko to neend bhi nahi aati”.

There is the tongue-in-cheek look at relationships: “Ta’alluq ashiq-o-mashuq ka to lutf rakhta hai/Mazze ab woh kahan baaqi rahe biwi-miyam ho kar”, and on ‘modern’ life: “Mai bhi hotel mein piyo chanda bhi do masjid mein/Sheikh bhi khush rahe Shaitan bhi bezar na ho”.

Like lawyers, he complimented the modern medical profession too:

“Inko kya kaam hai muravvat se apni rukh se yeh munh na morhenge/Jaan shyad farishte chorh bhi den doctor fees ko na chorhenge”.

There was a brilliant evocation of the slowness of British moves to home rule: “Reform ka shor hai, magar asar uska hain gayab/Plateon ka sadaa sunta hoon, magar khaana nahi aata”, or of electoral politics:

“Rahman ke farishte go hai bahut muqaddas/Shaitan ki jaanib lekin majority hai”.

And then, there is advice:

“Jab gham huya charha li do bottalen ikatthi/Mullah ki daurh masjid ‘Akbar’ ki daurh bhatti” and homage to his hometown: “Kuch Allahabad mein samaan nahi bahbud ke/Yaan dhara kya hai baa-juz ‘Akbar’ ke aur amrud ke”.

‘Akbar’ can be accused of many things, but never of being boring!

source: http://www.ummid.com / Ummid.com / Home> Life & Style / by Vikas Datta, IANS / April 01st, 2023