JAMMU & KASHMIR:

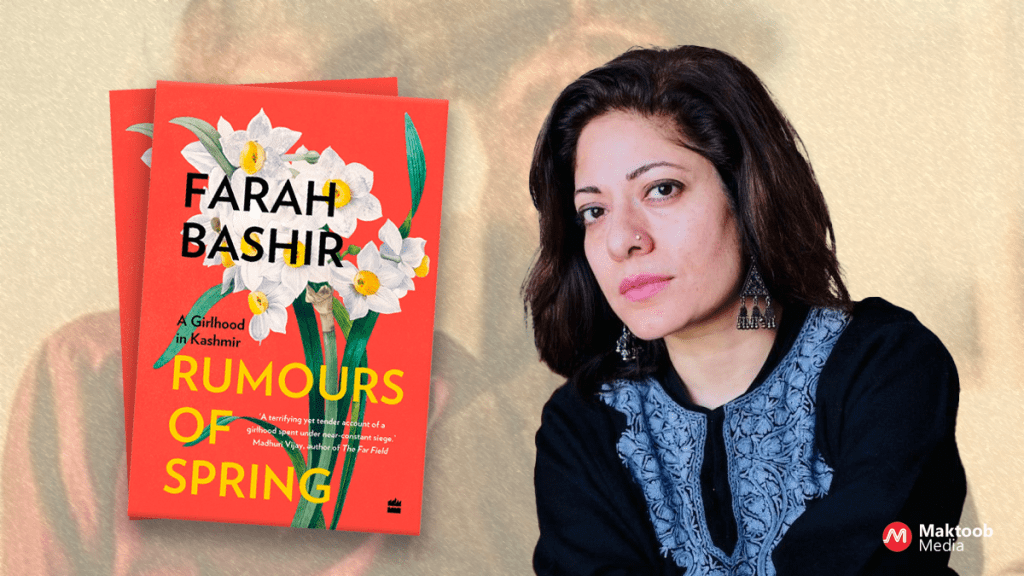

Erstwhile Reuters photojournalist, Farah Bashir’s memoir is a timely and crucial intervention in South-Asian studies. As the title of the book suggests, it is the true story of a girlhood spent in the midst of military occupation and militancy. Launched almost two years after the abrogation of Article 370 by the Indian state, which gave Kashmir a special status in terms of autonomy, followed by an undemocratic lockdown of the state along with house arrest of eminent Kashmiri politicians and communications blackout.

This coming-of-age memoir uncovers the truth about the everyday struggles of Kashmiris in the aftermath of the 1980s, in the land of curfews, gunfights and surveillance.

This memoir also offers a peek into the lives after the abrogation of Kashmir’s special status, which has often been compared to the 1980s Kashmir (Rafiq, 2019). Amidst all the information and knowledge available about Kashmir, Bashir’s novel stands out as one of a kind that puts forth the complexities of a girlhood spent in a conflict zone.

As a memoir, the style of the novel is compelling, to say the least. Although written primarily in English, the book through its usage of Kashmiri language in various interactions between the characters is rooted in the Kashmiri culture, language and traditions. The title of the book is also attributed to famous Kashmiri poet Agha Shahid Ali’s poetry, which she acknowledges as “a place of refuge for years”. (Bashir, 2021)

The book begins with Bashir, as an eighteen-year-old girl, preparing for her beloved Bobeh’s (grandmother’s) funeral procession as she is remembering the previous night she spent with her Bobeh and how she would have been “more polite” (Bashir, 2021) to her had she known it was their “last one together.” (Bashir, 2021) The present, throughout the novel, mingles with the past as Bashir reminisces both poignant and cheerful times of her adolescence spent amidst conflict.

Bashir’s memories take the readers to the Eid of 1989 when she was stuck in a market because of a sudden announcement of curfew. She ends the chapter by disclosing a habit she developed after the incident – pulling out her own hair, which is later reviled to be a consequence of PTSD. Bashir’s memoir reveals many such incidents that not only discuss the violent sounds of gunfire, the cruel silence of curfew or the horrifying cordon searches, but also the perpetual talks of death and murder that form a part of everyday realities in Kashmir.

While Kashmir is largely seen through a political, military or diplomatic angle, what Bashir does through her novel is, she portrays how even simple daily life activities in Kashmir are laden with terror. The chapter titled, The Country with a Burnt Post Office, talks about the heart-wrenching love story that tragically burns along with the only possible way of communication- the Post Office. She plaintively calls her break-up with her lover “neither painful nor acrimonious” (Bashir, 2021) but “a romance that was cut by fire” (Bashir, 2021).

Young girl’s school life also faces upheavals that not only torment her everyday life at school but also her dreams. Bashir dreams about absent girls in school which “sometimes presented the reality as it were” (Bashir, 2021).

Familial relationships are explored with utmost honesty in this 228-paged memoir. Bashir’s keen eye even as a young girl never missed the perturbing face of her mother as she makes little knots in her scarf, awaiting the unusually late father, the lecherous gaze of troops stationed in every nook and corner, her bobeh’s deteriorating wheezing, or her father’s ever worrisome face.

Bashir writes the memoir in the way memoirs are supposed to be honest. She further mentions her love for music as a young girl and her quest to save the music system from frustrated troops as they cordoned their house. Bashir’s memoir is a reminder that things as fundamental as music are under scrutiny in military occupation, that listening to music in itself forms a part of everyday resistance in war-torn zones.

Rumours of Spring takes us through the games that she sees her neighbours play- in the chapter titled “Games our children play” Bashir very smoothly walks us through one of the most harrowing effects of occupation – the echoes of brutal realities in children’s games, Bashir delineates the incident with Omar and Ahmad – where Omar along with his friends pretends to be a kidnapper and abducts studious Ahmad while he is on his way back home and later mocks him for his delayed reaction by calling Ahmad a “Proper Coward” (Bashir, 2021, p. 198).

As young Bashir watches and listens to Omar’s recital, she can’t help but imagine what must Ahmad have thought to have such a delayed reaction to his brother’s prank – “vice-chancellor Mushir-ul-Haq’s kidnapping and killing?” (Bashir, 2021, p. 199). She further looks back on the games they used to play before 1989 and how they disappeared with imposed evening curfews.

Bashir’s memoir is, thus, not just her own, it is the memoir of her people, a whole generation of Kashmiris and another generation of Kashmiris too, who have faced communications blackout, curfew and surveillance as long as they can remember. In many ways, the memoir transcends the space and time it is set in, it’s also crucial to note that Bashir’s memoir is in no way implying a universal experience, but through its individuality, it maintains the essence of humanity. Through her painful yet simplistic descriptions of PTSD and anxiety, Bashir gives us a glimpse into one of the most ignored, yet most prevalent issues among children in a conflict zone.

Bashir’s honest tackling of such a sensitive issue is bound to make readers take a look at the rising number of mental health issues, widespread in children as well as adults of conflict zones.

In this 228-paged memoir, Bashir is able to write her own story, while also representing her fellow Kashmiris. The ubiquitous simplicity, the sincere descriptions, the bitter-sweet moments and the familial relationships in this memoir, is what makes it stand out.

The cobwebs of lies perpetrated by State machinery about Kashmiri women being mere victims at the hands of militants and State- security forces being their saviours, is coherently and comprehensively shut down. This memoir is a resistance in itself, it is a crucial read for anyone interested in South Asian politics and also for those interested in the myriad vastness of human experiences.

Bashir’s memoir is a reminder to humankind, its timely release is a strong plea to the world to take a look at the ever-worsening situation of Kashmir. Rumours of Spring makes its place amidst countless memoirs, fiction and non-fiction that form a part of Kashmiri literature and show the truth against the barefaced lies produced by those in power. Farah Bashir’s memoir is an epistemic resistance to the epistemic violence perpetrated by the State-backed, Machiavellian and megalomaniac modus-operandi of the modes of knowledge productions on Kashmir.

Bibliography

Bashir, F. (2021). Rumours of Spring. Thomson Press, India.

Rafiq, A. (2019, August 29). In Afghanistan and Kashmir, It’s the 1980s All Over Again. Foreign Policy Insider. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/29/in-afghanistan-and-kashmir-its-the-1980s-all-over-again/

Shambhavi Siddhi completed her master’s degree in French and francophone literature from JNU. She is currently pursuing a PG Diploma in Women’s and Gender Studies from IGNOU.

source: http://www.maktoobmedia.com / Maktoob Media / Home> Bookshelf / by Shambhavi Siddhi / November 25th, 2021