Aonia,Bareilly / Aligarh – UTTAR PRADESH :

Why a flag-bearer of modern Urdu poetry chose to be moderate

In 1936, Munshi Premchand made a seminal speech, Sahitya ka Uddeshya(‘The Aim of Literature’), to the Progressive Writers’ Association. While asserting that literature is meant to critique society, the novelist said it can never regress into propaganda. The point applies to the work of Shahryar, who was born, reportedly, in the same year. For, while being a self-avowed Marxist, he refused to be bracketed into the categories of ‘modernism’ or ‘progressivism’. Finding his voice in the post-Nehruvian period of disillusionment in the 1960s, he turned his gaze inward, into the inner struggles of an individual, while not remaining oblivious of the external environment.

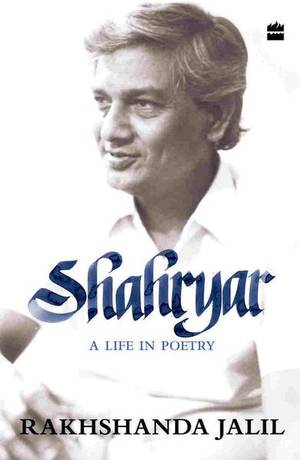

Rakhshanda Jalil stresses in Shahryar: A Life in Poetry that his tone was one of moderation. The poet, who was among the flag-bearers of the jadeed (modern) shayari, did not declaim, he whispered into the reader’s ears his thoughts on social issues. One example is Ek Siyasi Nazm (A Political Poem), where he gently chides a neighbour who has passed on his communal hatred to his children.

Some of the leitmotifs that occupied the poet’s imagination were sleep, dreams and night. His most famous collection, Khwab ke Dar Band Hain (The Doorway to Dreams is Closed), paid tribute to his favourite theme, khwab (dream). In its title nazm, he presents the night as freeing the eyes of the protagonist not only of all ‘sins’ but also of dreams, an act that he calls a punishment.

The poet, among the four Urdu writers to have been given the Jnanpith, is remembered outside Urdu literary circles, and especially among cinephiles, for his association with filmmaker Muzaffar Ali. The partnership resulted in Gaman, Umrao Jaan, Anjuman and the incomplete Daman and Zooni. It is when Jalil delves into this side of Shahryar that her arguments become a bit problematic, especially when she says that there exists a dichotomy between film lyrics and poetry.

Here, Sahir Ludhianvi’s write-up to his fellow poets is instructive. While Ludhianvi acknowledged that a nagma nigar (lyricist) doesn’t have the freedom of an adabi shayar (poet), as he is constrained by the film’s screenplay and characters, he added that his own attempt was to elevate film lyrics to the status of high art. It is when a film’s lyrics rise above its mere narrative that they take the form of art. What Jalil ignores is that a poetry lover would use such lyrics as a trigger to delve deeper into a poet’s corpus. An appreciation of Seene Mein Jalan won’t stop at listening to the song; it would progress to a reading of Ism-e-Azam, the collection from where the ghazal was taken.

Shahryar: A Life in Poetry; Rakhshanda Jalil, HarperCollins, ₹599.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books> Reviews / by Hari Narayan / October 13th, 2018