BRITISH INDIA :

Skull of soldier, executed by the East India Company for rebellion in 1857, found its way to London pub; it’s now with historian Kim Wagner

Headhunting is usually associated with primitive tribes and contemporary terrorists, but the colonial rulers of India also collected heads of Indian soldiers as war trophies.

A 160-year-old skull of sepoy Alam Beg, now in the possession of a historian in London, is proof that colonial rulers who brought many modern practices to India were also at times inhuman.

In 1857, Alam Beg, also known as Alum Bheg, was a soldier with the 46th Bengal Native Infantry, an arm of the East India Company.

The Mutiny that year, after having covered the north Indian heartland, spread to Sialkot (now in Pakistan), where Alam Beg and his companions tried to follow their fellow soldiers and attacked the Europeans posted there. On July 9, 1857, they killed seven Europeans, including an entire Scottish family.

Alam Beg, along with his comrades, left Sialkot and trekked all the way to the Tibetan frontier only to be turned away by the guards on the Tibetan side. He was reportedly arrested from Madhopur, a scenic town on the northern part of the Indian Punjab and taken back to Sialkot. A year later, he was tried for the brutal killing of the Scottish family and blown up from the mouth of a cannon. The Mutiny ended soon after. Alam Beg’s tragic story surfaced more than a century later thanks to an Irish captain Arthur Robert George Costello, who was present at his execution.

Present at execution

The Irishman was a captain in the 7th Dragoon Guards, dispatched to India after the Mutiny had shaken the bonds between the East India Company and the native soldiers. Costello had not seen any episodes of the Mutiny but was present at the execution, said historian Kim Wagner, who possesses the skull now.

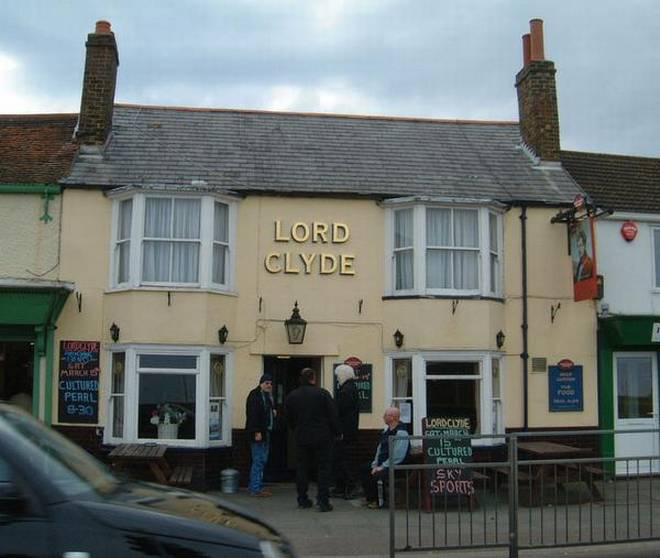

Costello picked up the skull and returned to London with it. In 1963, the skull was discovered in a store room of The Lord Clyde pub of London, after it had changed hands. The new owners were less than happy to find this war ‘trophy’ from 1857, but treated it as a solemn object from a disturbing past of British history in the subcontinent. The owners of the pub learnt from a note left in an eye socket that it belonged to Alam Beg, who played a leading role in the mutiny of sepoys in Sialkot. They desired to repatriate the skull to the soldier’s family. For years, they tried but failed. It is not known how the skull of Alam Beg ended up in the Victorian-era pub. But it is possible that the Irish captain who witnessed the execution of the leader of the mutinous soldiers visited the pub or someone deposited it there, given the fact that it had links with the history of the Indian Mutiny. In fact the pub was named after Collin Thomson, also known as Lord Clyde, who was a military commander and played a role in crushing the mutiny in north and northwest India. So it is possible that soldiers after their Indian stint would visit the pub.

In 2014, the owners of the pub contacted Kim Wagner who has been writing about South Asian history for years. They urged him to take the skull and return it to the descendants of Alam Beg. Mr. Wagner brought it home and the skull finally added to his research on South Asia which was published late last year as “The Skull of Alum Bheg: The Life and Death of a Rebel of 1857.” The historian believed that only by making people aware of the skull that Alam Beg can be returned to his motherland.

His research showed that most of the soldiers of the 46th Bengal Native Infantry were from modern states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar and Havildar Alam Beg most probably hailed from Uttar Pradesh. Though he wanted to return him to a dignified family grave yard of Beg’s family, it was not possible as the East India Company left no records of the soldiers of the 46th Bengal Native Infantry.

“There are no longer any records for sepoys of the Bengal Army – the best I could do was locate the area where the 46th regiment recruited from,” Mr. Wagner said.

The Mutiny of 1857 was crushed mercilessly and many gruesome incidents of that era find mention in official records. In 2014, around the time when Mr. Wagner began writing his book on Alam Beg, Ajnala in Punjab’s Amritsar hit the headlines when authorities discovered skeletons of 282 soldiers who were executed after the Mutiny. They apparently had surrendered hoping for a fair trial, but the Deputy Commissioner of the district Frederick Henry Cooper ordered execution of the rebels. They were buried with medals and even money of the East India Company that many of them had in their pockets. The grisly discovery is yet to receive a closure as the family members of those soldiers remain untraced.

Similar is the condition of Alam Beg as his journey back home remains incomplete but Mr. Wagner believed that his only physical remain should find a proper peaceful burial. Mr. Wagner is aware that the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been vocal about honouring the fallen soldiers of India in various colonial era battles. He says that something similar can be done in case of Alam Beg as well.

“After all these years, it is high time for Alum Bheg to return home…he was probably born in what is today India, he was executed in what is now Pakistan,” Mr. Wagner wrote in his book proposing that a burial for Alam Beg near the India-Pakistan border would be the most suitable tribute to his sacrifice.

The historian said that in the absence of the descendants of such soldiers, it is the Indian government that should bring back Alam Beg to his motherland.

Headhunting by colonial rulers from Europe was a rampant practice in the 19th century and activists worldwide have been vocal in demanding human remains from Western museums and collectors should be returned to their countries of origin. Such a movement is yet to begin in India whose soldiers from the colonial past in many instances continue to remain anonymous and abroad.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> News> National / by Kallol Bhattacharjee / New Delhi – February 04th, 2018