NEW DELHI :

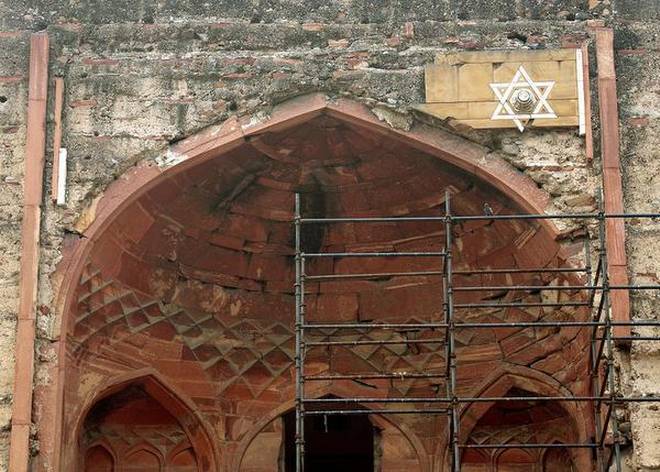

Rahim’s tomb, inspiration behind the Taj Mahal, was about to collapse when it was rescued by a conservation project

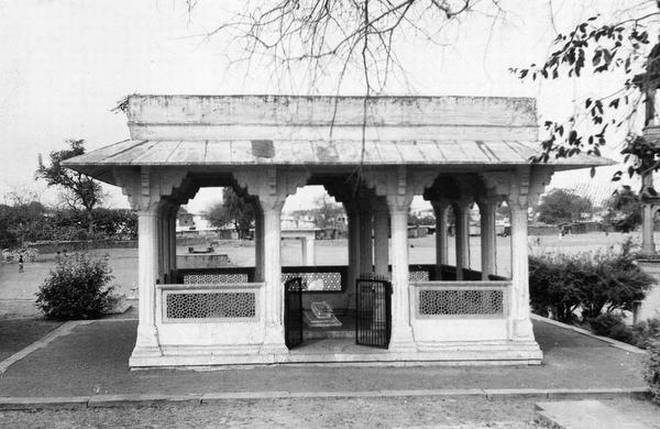

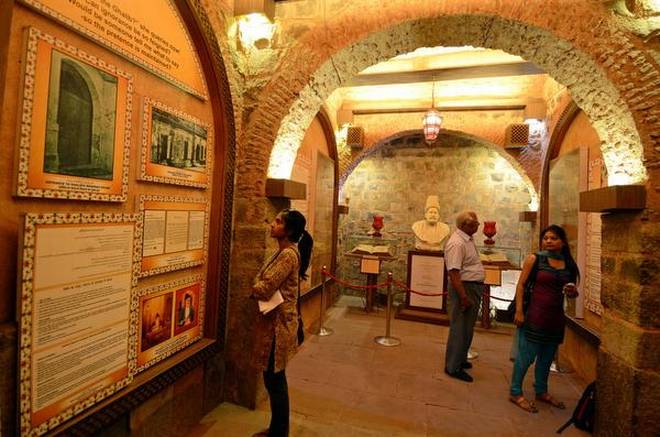

Some 50 years before that magnificent monument of love, Taj Mahal, was built, Abdur Rahim Khan-e-Khanan, a poet and diwan in Emperor Akbar’s court, built a tomb in the memory of his wife Mah Banu. It was the first Mughal tomb built for a woman.

Constructed in 1598, the tomb stands a few hundred meters south of the Humayun’s Tomb, a world heritage site, in Delhi. This location was chosen for its proximity to Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya’s Dargah — it was considered auspicious to be buried near the grave of a saint. Rahim too was eventually buried here in 1627.

Located near one of Delhi’s busiest roads, Mathura Road, Rahim’s tomb remained largely ignored for several years.

Then in 2014 the Ministry of Culture requested the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) to restore Rahim’s tomb.

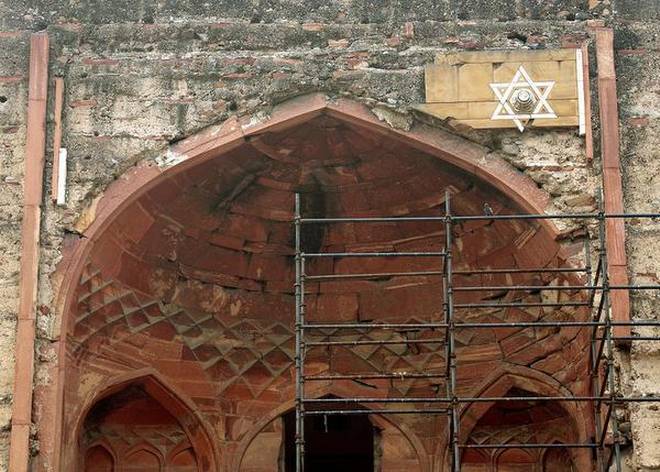

The tomb’s condition was precarious, to say the least, when the project began. “I usually don’t say this, but this building could have collapsed,” says Ratish Nanda, AKTC’s Chief Executive. It was “a very complex” project, he says. The restoration began in association with the Archaeological Survey of India and funding from InterGlobe, an Indian conglomerate.

There were deep cracks in the crypt, the first floor and the dome – “some so wide that you could put your arm through them.”

This needed immediate attention, and he realised it would take up to a year to fix them. Vandalism had added to the structure’s deterioration. Stones were missing, the white marble on the dome had been stripped off, water was seeping through. A flood a few years ago had also created cracks in the crypt’s vault.

Kilos of concrete

The restoration that had been attempted previously was woefully inappropriate and used modern plaster and cement, and had compounded the problem.

AKTC had faced a similar challenge during their restoration of Humayun’s Tomb, where they had to remove over a million kilos of concrete. The tomb wasn’t particularly structurally sound to begin with either, much like Humayun’s Tomb.

The team began with architectural documentation. This involved 3-D laser scanning (a technique first developed to find leaks in nuclear plants), photo archival research, historical research. Every stone was drawn up.

In 1968, the renowned British historian Percy Brown identified Humayun’s and Rahim’s tombs as structures that inspired the Taj Mahal. “But what is most significant about Rahim’s tomb,” Nanda says “is Rahim.” Rahim was just four when his father, Bairam Khan, an important military commander in the Mughal army, was assassinated. He grew up under the foster care of Emperor Akbar. He would later become one of Akbar’s nine most important ministers, the Navaratnas, and prove his own capability as a commander.

Most of us, however, know Rahim better as a poet. Apart from his famous dohas, he also wrote verses in Arabic, Sanskrit and Turkish, and translated Emperor Babur’s autobiography, Baburnama, from Turkish to Persian.

“I like the idea of this multidimensional personality. [He is] almost a renaissance figure,” says former diplomat T.C.A. Raghavan, whose curiosity about Rahim eventually led him to write a book about the man and his father, Attendant Lords (2017).

Secular symbol

Ujwala Menon, a conservation architect with AKTC, says that he was a secular figure and a patron of architecture. “The water supply system that he built in Burhanpur, with underground pipelines to every part, we can’t replicate that even today.”

Menon says that an attempt will also be made to restore the grand garden with plants that the Mughals favoured, such as citrus orchards.

A project of this scale requires several layers of work — preservation to keep the building in the state that it is found, restoration to bring the structure as close to its original condition as possible and reconstruction, which also involves a technique called ‘anastylosis’, where a ruined building or a broken object is restored using its original material. The vaults and parapet here were reconstructed using new pieces of Delhi quartzite and red sandstone respectively. Paint and lime-wash layers had to be painstakingly removed to reveal the incised geometric and floral patterns.

It will be another 16 to 20 months before the restoration of the tomb is complete, as there is major structural work to be done on the dome and facade.

But views on conservation can be subjective. There are those who criticise the work being carried out, saying that such techniques take away the narrative of age from the structure. Some believe that preservation is the only correct conservation technique.

But critics often focus on the aesthetics, not taking into account the structural integrity of the building. Nanda illustrates this with the analogy of skin. “You cannot say, ‘oh my skin is falling off, but I won’t repair it.’ Skin, besides making you look like who you are, is also fulfilling a lot of other functions.”

It is to counter such ‘mad arguments’ that Nanda says AKTC got the project extensively peer reviewed by over 50 different individuals — from architects, archaeologists and engineers, to historians, journalists and bureaucrats. These included Jaya Jaitly, Narayani Gupta, Saleem Beg, William Dalrymple, Gillian Wright and Lynn Meskell.

Nanda says that AKTC doesn’t take up a project unless the work can benefit local people. The Nizamuddin Basti Urban Renewal Initiative, of which the Rahim tomb renovation is a part, has also generated over five lakh man days of work for master craftsmen.

Earlier this year, a book, Celebrating Rahim, was published about Rahim’s life and and his artistic, political and intellectual work. AKTC and InterGlobe hope to bring out a compilation of Rahim’s written verses as well.

Nanda is appreciative about the private sector involvement in the project. “Unless there is a huge public interest in conservation, the future of heritage conservation is bleak.”

When he’s not chasing stories, the writer can be found playing Ultimate Frisbee or endless rounds of Catan.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Society> History & Culture / by Shashank Bhargava / March 17th, 2018