The emergence of artistic and cultural heritage of a country is a process that extends over centuries. Yet, sometimes, it can just take just a few days for it to vanish irrevocably. Care must be taken to preserve our heritage

Indian civilisation is one of the foremost in the world in terms of cultural wealth and the great works it produced. The indigenous people of India played a major role in the creation of the civilisation. However, people of diverse cultures from outside the peninsula have also doubtlessly contributed to the creation of this tremendous cultural wealth. One among such people are the Turks who led an amiable coexistence alongside the Indian people for decades.

In the first half of the 11th century, a great Turkish Sultanate was founded in northern India and subsequently Turkish influence extended further south. The foundation of this state had a notable impact on the history and culture of India. As a result of this impact, Delhi flourished to the point of competing with Baghdad, Cairo and Istanbul — the leading commercial and cultural centers of the world at that time.

Here onwards, the Turkish-Islamic influence began to shape all cultural areas from architecture and literature to arts and cuisine. Concrete examples of this impact can still be seen today. The centuries-long co-existence of both Indian and Turkish culture led to the exchange of words between the Turkish and Indian languages despite their vast structural differences. Some Turkish words were directly adopted as they were, while some words were transcribed according to their Indian pronunciations.

The most prominent aspect of the Turkish influence in India, however, is reflected in architectural works, with its myriad examples. One such example is the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque that was constructed by Qutab Ud-Din-Aibak, the founder of the Delhi Sultanate. It was the construction of this mosque that laid the foundation of the Indo-Islamic architecture in India. The famous ‘Qutb Minar’ minaret, which was constructed by Qutab Ud-Din-Aibak in 1500, is a 72.6 meter tall tower built of red sandstones, based on the Mamluk architectural style.

Following the Qutb Minar, many castles, palaces, tombs, granaries, bathhouses, ponds, mosques and even cities were built throughout India during the Mughal period. Akbar Shah’s rule was particularly marked by the mixed use of Persian style and Indian/Buddhist style architectural design, thus giving rise to a new and unique type of architecture. Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, the Fatehpur Sikri Fortress, which was declared the capital of the Mughal Empire by Akbar Shah, and Akbar’s own tomb in Agra are some of the chief examples of this style. And, of course, let us not forget the exceptionally beautiful Taj Mahal.

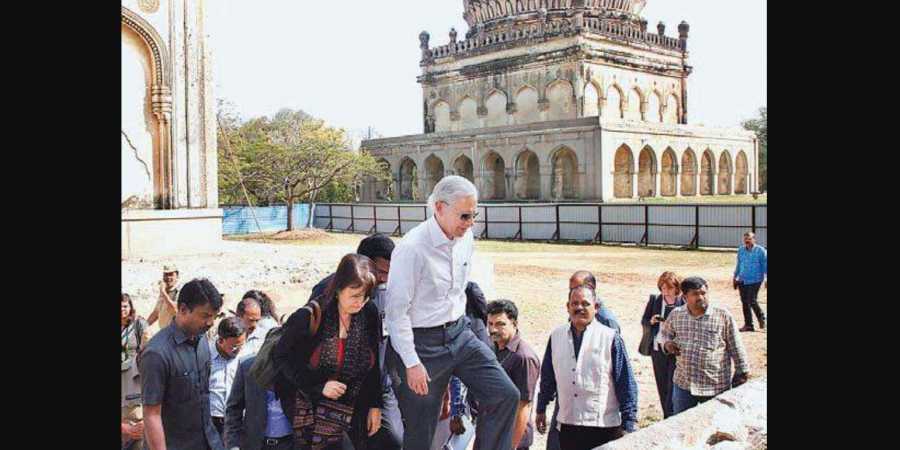

Although the Indian state is seemingly responsible for the preservation of all these great works, there are examples reflecting the importance of personal initiatives. Esra Birgen Jah, the former princess of Hyderabad, is one such example. Born as the daughter of a family from the Ottoman Dynasty, and the first wife of Barkat Jah, the Nizam of Hyderabad, Esra Birgen Jah successfully restored the Chowmahalla Palace to its former glory after lengthy efforts.

A great many people from diverse disciplines such as architect, textile specialists, conservationists and historians took part in the restoration efforts. The palace, which was turned into a museum housing historical artifacts, costumes and documents, was presented with a UNESCO award.

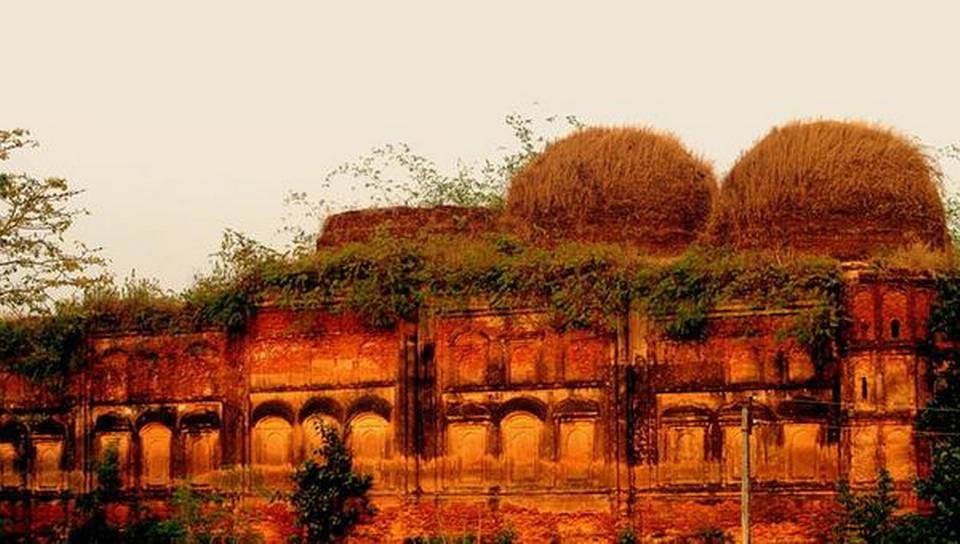

Whether their origins date back to Turkish or other cultures, all historical monuments in India should be recognised as ‘cultural heritage,’ and provided with the protection they deserve. For this reason, the great works in India, which have seen the rise and fall of the civilisations of the past, witnessed countless major events and developments in the history of humankind, and stood as a testament to ‘history’ itself, needs to be restored and conversed so that the human history can be preserved and passed down to the next generations.

Today, the Turkish heritage on the Indian peninsula is considered India’s own property. Their preservation should be viewed as a key factor that will help reinforce Turkish-Indian relations and friendship, and Turkey should provide the necessary support to the Indian Government in this regard.

The emergence of the artistic and cultural heritage of a country is a process that extends over the course of centuries yet sometimes, it can take just a few days for this cultural heritage to vanish irrevocably. Be it Indian or Turkish, all nations should take good care of the historical works within their domains and consider them as the common heritage of humankind.

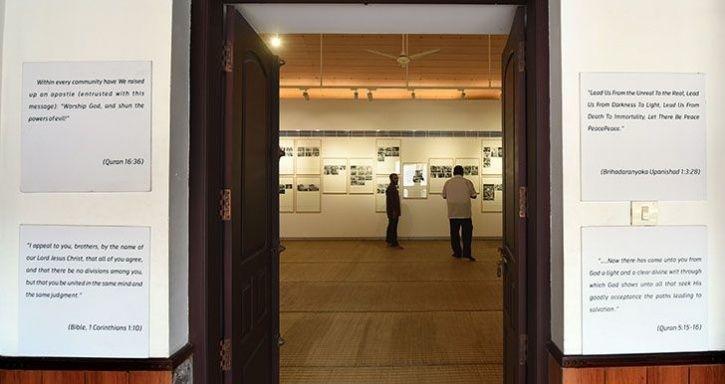

Wherever this common heritage may be located in the world, it should be preserved to the utmost from ethnic and religious conflicts, exploitation, negligence and, of course, the destructive forces of time. This will awaken interest in different cultures among nations and render peace. In this way, the Indian and Turkish people, already linked by a historically strong bond of brotherhood, can usher in a new era that will recapture and consolidate the spirit of fraternity.

(The writer is a Turkish author)

source: http://www.dailypioneer.com / The Pioneer / Home> Columnists> OpEd / by Harun Yahya / April 02nd, 2018