UTTAR PRADESH :

He is truly a forgotten warrior of the freedom movement. Few know about him and fewer are familiar with his name but delve into the pages of history and you realise that he deserves a better place.

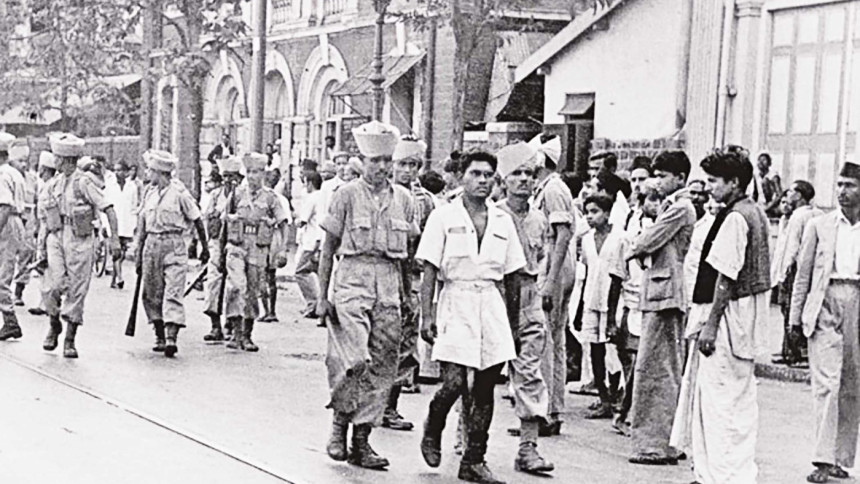

He participated in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 in the Battle of Shamli between the British and the anti-colonialist ulema. The scholars were ultimately defeated at that battle.

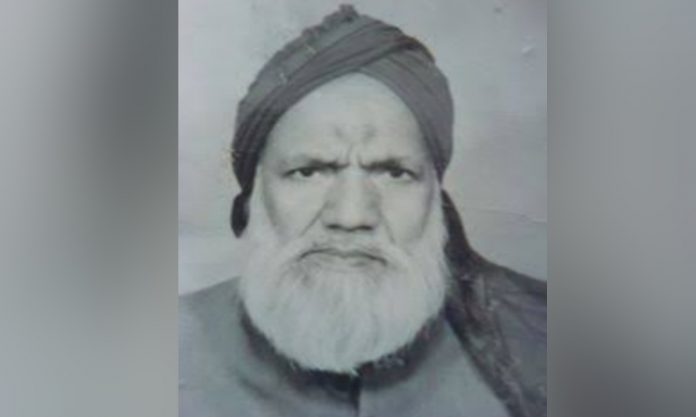

He was Mohammad Qasim Nanautawi.

Nanautawi was born in 1832 into the Siddiqui family of Nanauta, a town near Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh.

He was schooled at Nanauta, where he memorised the Quran and learned calligraphy.

At the age of nine, Nanautawi moved to Deoband where he studied at the madrasa of Karamat Hussain. The teacher at this madrasa was Mehtab Ali, the uncle of Mahmud Hasan Deobandi.

On the instruction of Mehtab Ali, Nanautawi completed the primary books of Arabic grammar and syntax.

Thereafter, his mother sent him to Saharanpur, where his maternal grandfather Wajihuddin Wakil, who was a poet of Urdu and Persian, lived.

Wakil enrolled his grandson in the Persian class of Muhammad Nawaz Saharanpuri, under whom, Nanautawi, then aged twelve, completed Persian studies.

In 1844, Nanautawi joined the Delhi College. Although was enrolled in the college, he would take private classes at his teachers’ home, instead of the college.

Nanautawi stayed in Delhi for around five or six years and graduated, at the age of 17.

After the completion of his education, Nanautawi became the editor of the press at Matbah-e-Ahmadi.

During this period, he wrote a scholium on the last few portions of Sahihul Bukhari.

Before the establishment of Darul Uloom Deoband, he taught for some time at the Chhatta Masjid. His lectures were delivered at the printing press. His teaching produced a group of accomplished Ulama, the example of which had not been seen since Shah Abdul Ghani’s time.

In 1860, he performed Haj and, on his return, he accepted a profession of collating books at Matbah-e-Mujtaba in Meerut. Nanautavi remained attached to this press until 1868.

In May 1876, a Fair for God-Consciousness was held at Chandapur village, near Shahjahanpur.

Christians, Hindus, and Muslims were invited through posters to attend and prove the truthfulness of their respective religions.

All prominent Ulama delivered speeches at the fair. Nanautawi repudiated the Doctrine of the Trinity, speaking in support of the Islamic conception of God.

Christians did not reply to the objections raised by the followers of Islam, while the Muslims replied to the Christians word by word and won.

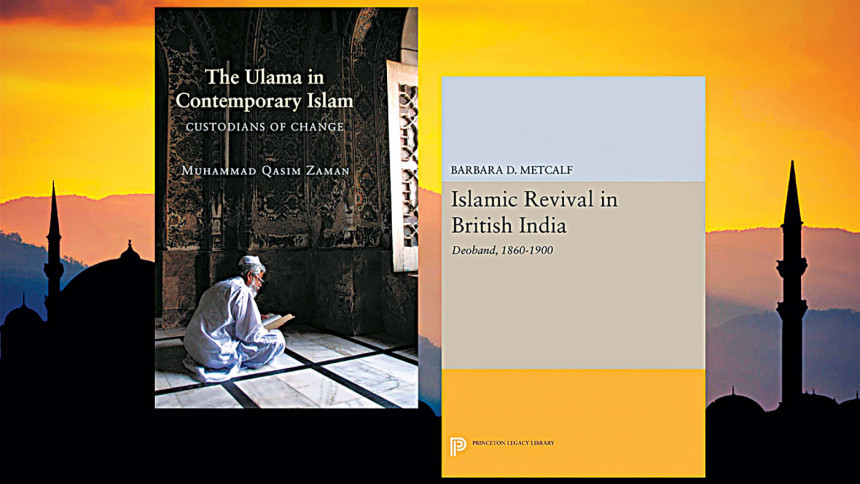

Mohammad Qasim Nanautawi established the Darul Uloom Deoband in 1866 with the financial help and funding of the Muslim states within India and the rich individuals of the Muslim Indian community.

He conformed to the Sharia and worked to motivate other people to do so. It was through his work that a prominent madrasa was established in Deoband and a mosque was built in 1868. Through his efforts, Islamic schools were established at various other locations as well.

His greatest achievement was the revival of an educational movement for the renaissance of religious sciences in India and the creation of guiding principles for the madaris (schools).

Under his attention and supervision, madaris were established in several areas.

Under Muhammad Qasim Nanautvi’s guidance, these religious schools, at least in the beginning, remained distant from politics and devoted their services to providing only religious education to Muslim children.

Nanautawi died on 15 April 1880 at the age of 47. His grave is to the north of the Darul-Uloom.

Since Qasim Nanautawi is buried there, the place is known as Qabrastan-e-Qasimi, where countless Deobandi scholars, students, and others are buried.

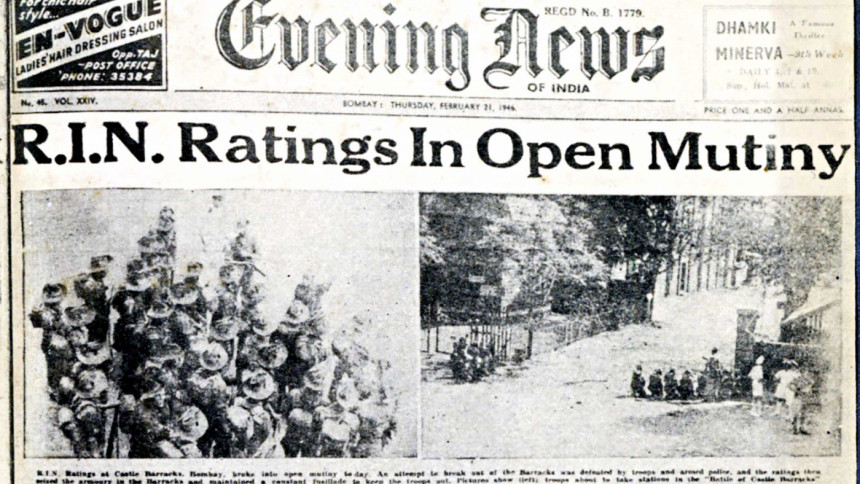

Significantly, the elders of Deoband took more and more part in the struggle for the independence of the country.

After the establishment of Darul-Uloom, the period of participation in national politics began.

Darul-Uloom, Deoband, was a centre of revolution and political, training. It nurtured such a body of such a body of self-sacrificing soldiers of Islam and sympathisers of the community who themselves wept in the grief of the community and also made others weep; who themselves tossed about restlessly for the restitution of the Muslims’ dignity and caused others also to toss about.

They shattered the Muslims’ intellectual stagnation, they broke up the spell of the British imperialism, and, grappling with the contemporary tyrannical powers, dispelled fear and anxiety from the minds of the country.

They also kindled the candle of freedom in the political wilderness.

It is a historical fact that the political awakening in the beginning of the twentieth century was indebted to Deoband and some other revolutionary movements in the country, and the revolutionary freedom-lovers who rose up there were the products of the grace from the spring of thought of Deoband.

Then, after the establishment of Pakistan, the Indian leaders of Deoband guided the Indian Muslims in utterly adverse circumstances and helped keep up their spirits high. — IANS

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home / by Amita Verma / July 31st, 2022