Bhopal, MADHYA PRADESH :

Bhopal, MADHYA PRADESH :

Faizabad, UTTTAR PRADESH :

Although Faizabad had acquired prominence during the reign of the early Nawabs of Awadh, it lost some of its lustre when, soon after taking over the reins of the kingdom in 1775, Nawab Asif-ud-Daula shifted the capital from Faizabad to Lucknow.

Yet, it continued to enjoy a lot of influence until the last Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was deposed and banished to Matia Burz near Calcutta (now Kolkata). It was so because of its famed Begums who wielded considerable political and financial clout. However, in the last century, a Begum of a different kind brought the town national recognition when, at the end of every gramophone recording, she would proudly announce: “Mera naam Akhtari Bai Faizabad”. For most of her performing career, Begum Akhtar was known as Akhtari Bai Faizabadi and she truly represented the refined composite culture of Faizabad that abuts the Hindu holy town of Ayodhya.

Last year, Vani Prakashan had brought out an excellent book on Lucknow that offered scholarly research along with useful touristic information. Titled ‘The Other Lucknow: An Ethnographic Portrait of a City of Undying Memories and Nostalgia’, it was edited by Nadeem Hasnain and was based on a research project sponsored and funded by the Ayodhya Shodh Sansthan (Ayodhya Research Institute), an autonomous organisation of the Uttar Pradesh government’s Department of Culture.

It’s a matter of rejoicing that this year, Vani Prakashan has published a companion volume on Faizabad with the help of the same Ayodhya Shodh Sansthan. The fact that this volume is in Hindi and it offers very detailed information about the historic town, its social and cultural life, and places of religious and cultural significance would warm the cockles of everybody’s heart. Hindi writer Yatindra Mishra, who recently won the President’s Golden Lotus award for his biography of Lata Mangeshkar, has edited this 640-page tome titled “Shaharnama Faizabad” (A Chronicle of Faizabad). A scion of the erstwhile ruling family of Ayodhya, Mishra’s love for Faizabad is evident in the care and fastidiousness with which he has performed this daunting task with the help of many experts including historians Salim Kidwai, Madhu Trivedi and Yogesh Pravin, Islamic culture scholar Mirza Shahab Shah and Kosala Museum’s Deshraj Upadhyaya, to name only a few. Mishra has not only edited the book but has also contributed a large number of detailed comments on the Faizabad region’s history and culture, making use of painstakingly done research into archival material and other sources.

The book is divided into five sections and opens with the history of Faizabad and the way its architecture and culture took shape under the Nawabs. After Nawab Saadat Khan ‘Burhan-ul-Mulk’ was awarded the Suba of Awadh by the Mughal Emperor, he built a temporary fort called Qila Mubarak near Lakshman Ghat in Ayodhya. After some time, he built a cantonment at a distance of five kms from Qila Mubarak and it was known as Bangla. During the reign of Nawab Mansur Ali Khan ‘Safdarjung’, Bangla acquired the name of Faizabad. This section also tells us a very interesting fact about the royal emblem of the Nawabs as it depicted fish (considered to be auspicious) along with the bow and arrow of Ram, the presiding deity of the adjoining Ayodhya. Detailed information about the arts, architecture, music, jewellery and ornaments, and prominent Nawabs and Begums and their Hindu and Muslim courtiers has been provided in this opening section.

The second section is one of the most interesting and valuable parts of this book as it deals with the events and heroes of the great revolt of 1857, often described as the First War of Indian independence.

Ripple effect

As is well known, the deposition of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah had also played an important role in spreading anger and anguish among the sepoys who hailed from the Awadh region in considerably large numbers. Mangal Pandey belonged to village Dugvan-Rahimpur of Tehsil Sadar in Faizabad district. We also come to know about Maulavi Ahmad Ullah Shah alias Danka Shah who, as early as in February 1857, had started condemning foreign rule in his public speeches. He was imprisoned and sentenced to death. Faizabad remained independent till January 6, 1858 and was defeated by the Nepalese army that attacked its forces and subdued them.

While the third section gives detailed descriptions of important religious places belonging to all the religions present in the region, the fourth section offers invaluable historical information about the writers, poets, courtesans, high-brow as well as folk musicians, folk art, village fairs as well as local festivals, bazaars and traditional haats, instruments and their makers, journalists, newspapers, magazines and printing presses of the region. It’s a fairly long list and offers a glimpse into the cultural richness of Faizabad.

The fifth and final section deals with prominent social workers, sportspersons, educational institutions and public libraries, thus completing a full circle. It’s not possible to discuss such a voluminous book in any detail here. Suffice it to say that those who are interested in knowing the history and culture of Awadh cannot afford to ignore this work.

source: http://www.thehindu.com / The Hindu / Home> Books / by Kuldeep Kumar / June 16th, 2017

Arcot, MADRAS (now TAMIL NADU ) / Faizabad, UTTAR PRADESH :

Faizabad

Built 200 years ago, Wesleyan Chapel, a fine specimen of British Architecture, for the British soldiers posted in Faizabad Cantonment, Church of North India is all decked up to celebrate Christmas.

Wesleyan Chapel, built in 1816, merged with Diocese of Lucknow in 1970 and then came to be known as Church of North India.

Talking to TOI, Rev Kaushalendra Solomon, pastor of the church said that special prayer service would be held at midnight on Christmas and then in the morning. Different religious activities will continue in the church till December 31and a special watch night service would be held on New Year eve.

The church committee led by secretary Chitij Charles has ensured special decoration with flowers and lighting as the Church has completed 200 years. Rev Solomon said that they get special cakes baked for Christmas celebrations at a local bakery.

“Ghulam Mohammad, a local scholar, said that Maulvi Ahmad Ullah Shah, who was leading the 1857 mutiny against Britishers from Faizabad, had instructed his soldiers not to damage the Wesleyan Chapel because it was a place of worship.”

source: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com / The Times of India / Home> Neww> City News> Lucknow News / by Arshad Afzal Khan / TNN / December 25th, 2017

Bhopal , MADHYA PRADESH :

An 18-year-old widow who declared her infant daughter queen; a wife who survived an assassination attempt and held her husband captive; a princess who abdicated the throne in favour of her mother; a ruler who served as the only woman chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University.

The erstwhile royalty of Bhopal has borne some of the bravest, most dynamic rulers in the 19th and 20th century India. These nawabs were popular, fair, reformist, and fierce; they were also women.

While several women have enjoyed power as regent mothers and influential wives throughout history, Bhopal and its royalty are unique. Between 1819 and 1926, the kingdom saw four women rule it – women who were Nawab Begums, not just Begums, who ruled through inheritance, not proxy.

The movie

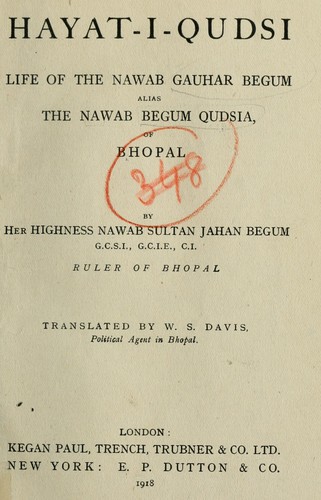

Much has been written about these women and their reign, including by the Nawab Begums themselves, documenting both the personal and the political events of their times.

The footprints they left behind have become part of Bhopal’s everyday life, informing and forming its consciousness and character. It is the exploration of this connect that has resulted in Begamon ka Bhopal, a short film, which is both an ode to the universal feeling of nostalgia, and a document of how an interaction with history can turn deeply existential and personal.

The movie has been directed by Rachita Gorowala, a 30-year-old alumna of Xavier Institute of Communications, Mumbai, and FTII, Pune, and will be available to viewers in January on filmsdivision.org.

Gorowala says she made the movie as her own experiment with truth: “A fascination with Pathan woman rulers who ruled Bhopal for over 100 years started me on Begamon ka Bhopal. A journey that may have begun on the lines of fascination with history became existential, introspective and deeper as an experiment with cinema.”

The movie speaks of a Bhopal long past, and seeks to conjure it up through a writer rooted in the city, a grandson who has preserved reels of films shot by his grandfather between 1929 and 1975, two royal descendants, a royal attendant.

The overarching emotion running through the movie is huzoon, a Persian word for powerful nostalgia, a longing for something lost but not gone. The characters speak of their own past lives, or their engagements and attempts to understand the past life of their city.

The emotion and the sense of old Bhopal is created through both audio and visual evocations – the magnificence and now the absence that marks palaces (Moti Mahal, Shaukat Mahal), the Taj-ul Masjid that is a solid link to the past and the present of the city. Music has been used powerfully – songs written and sung by Firoza Khan, one of the former royals who features in the movie – play like both a dirge and an ode.

“As a student of cinema, I learnt that a film is a medium of time and not of telling stories. Stories are meant to be heard and read. It is through juxtaposition of images and sounds that one creates an emotional journey,” says Gorowala.

Begamon Ka Bhopal is her first short film in the genre of poetic-realism, “a lyrical, musical, introspective journey”. “The movie is an ode to the times that once existed in Bhopal, through an everyday nostalgia that is lived by a writer, a film keeper and royal descendants. Each in their own way hold onto time and thus become it,” she says.

The movie has a lot of frames that show only parts, fragments – walking feet, hands busy with embroidery, dry rustling leaves – which seem to reflect the fragments in which we understand and engage with the past, the parts we hold on to, some passages, some stories that call out to us especially, and through which we try to understand the whole, through which we seek to anchor ourselves in the ocean of time.

The character Salahuddin, writer Manzoor Etheshaam, Nawabiyat descendants Firoza Khan and Meeno Ali, the royal attendant Zohra Phupo, all have important roles, the three women are symbols of the past and have survived into the present, the two men belong to the present and are trying to hold onto their connect with the past.

There is a powerful scene of Firoza fingering dolls as she talks of her own moulding into a member of a royal family post her marriage in 1961; she talks as she dresses up, her begum-ness coming alive with each addition of earrings, kangan, kaajal.

The Begums

For her movie, Gorowala had rich material to draw on. Bhopal’s famous Begums had a lot of variety among them in terms of personality and traits – the first, Qudsia, defied her court’s nobles and conventions to declare her infant daughter King in 1819.

Qudsia ruled as proxy for her daughter for 18 years, defending her kingdom against the battering armies of the mighty Marathas – Scindias, Holkars, Gaekwads – and her daughter’s inheritance against internal opposition.

However, some nobles managed to convince the British that a woman ruler was un-Islamic. Thus began a period of daughters inheriting the kingdom and their husbands ruling it. Qudsia’s daughter, Sikander, was married to her cousin Jahangeer. Jahangeer proved unpopular. He even tried to kill his pregnant wife, but she escaped, took refuge in another fort, and subsequently managed to imprison him inside the fort.

Jahangeer died at 26, and once again, his six-year-old daughter Shahjahan was declared king, with power to pass on to her husband when she would get married.

However, Qudsia argued and harangued the British till this clause was removed. Thus, Sikander, and then Shahjahan, both ruled Bhopal as kings who inherited the kingdom. After Shahjahan’s death in 1901, her daughter Sultan Jahan ascended the throne.

While Qudsia was brought up illiterate and in purdah, she rose to the occasion when the need befell her. Sikander was raised to be king. Shahjahan was the most feminine and the least austere of the four, and wrote several books. Sultan Jahan went back to observing purdah, and was the first chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University.

After Sultan Jahan, the throne went to a man, her son Mohammad Hamidullah Khan. However, after Hamidullah died in1960 and his eldest daughter Abida Sultan migrated to Pakistan, his younger daughter, Sajida Sultan, came to power. Sajida’s husband was Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi, the grandfather of Saif Ali Khan.

Incidentally, Abida Sultan’s son Shaharyar M Khan, Pakistan’s former foreign secretary, authored the book, The Begums of Bhopal, on his path-breaking ancestors.

source: http://www.dailyo.com / Daily O / Home> Art & Culture / by Yashee @ yasheesingh / December 24th, 2017

Bombay (now Mumbai), MAHARASHTRA :

India’s fight against colonial rule was a long drawn out battle that gained momentum in several phases since it started in the early 20th century. Examples of these phases are the Non-Cooperation movement of 1920-22 and the Civil Disobedience movement of 1930-32. However, the one rallying call that gave the country its ultimate push towards complete independence was “Quit India”.

By far the strongest and most vociferous appeal made by the Indian National Congress (INC), “Quit India” asked the British, loud and clear, to leave India once and for all. Interestingly, contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t Mahatma Gandhi who coined this iconic slogan.

The son of a well-to-do businessman, Yusuf Meherally was born in Bombay on September 3, 1903. Fifty years earlier, his great-grandfather had established one of Bombay’s first textile mills and the family had prospered ever since.

As a young boy, Meherally was curious about the nationalist movements developing around him. While he was in high school, he would spend much time reading about the revolutionary movements of the different nations and the role youth had played in them. Having witnessed his family’s upper class prejudices all his life, the sensitive boy was also deeply affected by the struggles of the working class.

Having soon become a staunch supporter of the freedom struggle, young Yusuf was looked upon as an embarrassing renegade by his pro-British family. Unaffected by their disapproval, he joined the movement immediately after finishing his schooling from Bharda High School.

After earning a B.A. in History and Economics from Elphinstone college, he was studying law at the Government Law College in February 1928 when Simon Commission reached Bombay. A group of seven British Members of Parliament, the Simon Commission had arrived in India to suggest constitutional reforms but didn’t have a single Indian member. This unfair and insulting decision had led to much anger and disappointment among Indians.

Having founded the Bombay Youth League the very same year, Meherally immediately organised a protest against the Simon Commision. He had initially planned an ambitious expedition on boats to meet the members at sea itself, but the plan was leaked and the police took stringent steps to prevent it from happening.

Undaunted, Meherally and other young men dressed up as coolies to get access to the Bombay port where they greeted the members of the commission with black flags and the slogan “Simon Go Back”. The resolute demonstrators were lathi-charged thrice but they did not budge an inch. As the news of the demonstration spread like wildfire, establishments across the city began observing spontaneous hartals.

Overnight, Meherally’s courage and slogan were on everyone’s lips, including Mahatma Gandhi’s. Not only had he dared to shout his slogan to the face of a powerful British politician, he had also defied the directions of his political seniors who counselled inaction.

Threatened by his growing popularity and radical views, the British debarred him from practising law to the consternation of his family. The rarity of this action can be seen from the fact that though several nationalist leaders were lawyers, none of them had been barred from practising law.

Two years later, when the Civil Disobedience movement was launched, Meherally and his band of young volunteers worked tirelessly to keep the morale of the public up in face of the severe repressive measures that the British unleashed.

As INC’s prominent leaders courted imprisonment and went to jail during the Salt Satyagraha, Meherally kept the movement running till he himself was arrested in 1930 and sentenced to four month’s imprisonment.

In 1932, Meherally was again arrested for conspiracy and sentenced to a two-year term in the Nasik prison. It was here that he met and interacted with the radical socialist leaders of the freedom struggle.

After his release in 1934, he joined hands with Jayaprakash Narayan, Asok Mehta, Narendra Dev, Achyut Patwadhan, Minoo Masani and others to found the Congress Socialist Party. The organisation hoped to transcend communal divisions through class solidarity and bring about economic empowerment through decentralized socialism (i.e farmer co-operatives and trade unions).

In 1938, Meherally led the Indian delegation to the World Youth Congress in New York before attending the World Cultural Conference taking place in Mexico. Here, he was struck by the lack of literature on contemporary issues in India when compared to the West. Determined to fill this gap, he authored a series of books titled ‘Leaders of India‘ that focused on current topics and translated them to Gujarati, Hindi and Urdu.

Here is an excerpt from the foreword he wrote:

“The rise of the pamphlet and the booklet as a powerful weapon for the spread of ideas has been truly remarkable. During my visits to these continents (US and Europe) I was greatly impressed by the part that such brochures play in moulding public opinion. In Europe and America there exists a wealth of topical literature that is in striking contrast to its scantiness in India.

The Current Topics Series of Padma Publications is an attempt to meet this need. The idea is to publish every few months a booklet on a subject of topical or special interest having regard to present-day controversies and their bearing on the future. The series will not be restricted to political questions only. Every title will be published in a pleasing format, at a price within the reach of all.”

In the next few years, Meherally was arrested several times for defying prohibitory orders and participating in Individual Satyagraha (launched by Gandhi to affirm one’s right of speech and oppose the British decision to involve India in World War II without the consent of its people).

In 1942, he was still in Lahore Jail when he was nominated by INC for the election to Bombay Mayoralty.This nomination was personally backed by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel who knew that Meherally belonged to that rare breed of leaders for whom personal gratification meant ensuring the well-being of fellow countrymen.

Released from prison to participate in the elections, Meherally won comfortably, becoming the youngest Mayor in the history of Bombay’s municipal corporation. During his tenure, he became immensely popular among the public due to his dedication towards ensuring effective civic service.

One of Meherally’s first steps as a mayor was to introduce a quick dispatch system for files and deal with slacking officials with an iron hand. Other than personally attending to citizens’ complaints on civic issues, he took the unprecedented decision of refusing to pay municipal money for the British Government’s Air Raid Precautions (ARP) scheme.

The ARP scheme was a programme initiated for the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. It included the organisation of ARP wardens, messengers, ambulance drivers and rescue parties who would liaison with police and fire brigades in case of an air raid.

Earlier, Bombay’s municipal corporation used to pay Rs 24 lakh to the British government for the ARP scheme but an adamant Meherally argued that the defense of the city should be in the hands of those who would remain on the scene no matter what and not the British who would probably withdraw in case of an attack (just like they had done in Malaya and Burma).

This led to the organisation of the People’s Volunteer Brigade in Bombay and the city became the only one in India where the municipal corporation was allowed to run the ARP scheme.

All this while, he continued being involved in the country’s fight for freedom. On July 14, 1942, INC’s working committee had met at Wardha and demanded complete independence, failing which a massive civil disobedience movement would be launched.

Soon after, at a meeting in Bombay, Gandhi conferred with his closest associates on the best slogan for the movement. C Rajagopalachari suggested ‘Retreat’ or ‘Withdraw’ but it didn’t find much favour with the leader. It was Meherally who then came up with the succinct phrase — ‘Quit India’ — that got Gandhi’s approval.

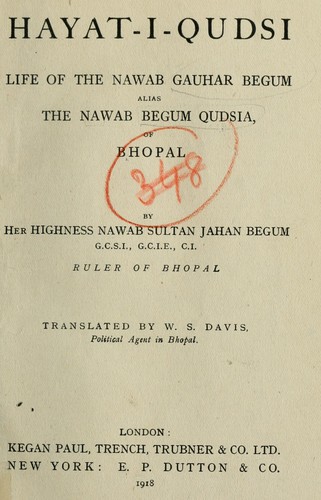

In preparation for the nationwide movement, Meherally published a booklet titled Quit India (that sold out in a matter of weeks) and got over a thousand ‘Quit India’ badges printed to popularise the slogan. On August 8, 1942, Gandhi delivered his powerful Quit India speech at Mumbai’s Gowalia Tank Maidan. The next day, he was arrested along with practically the entire INC leadership.

Realising that these arrests had created a vacuum in the communication between the leadership and the masses, Meherally immediately mobilized his socialist colleagues – Aruna Asaf Ali, Ram Manohar Lohia and Achyut Patwardhan – to take charge of the Quit India movement while hiding underground, just before he himself was caught and put in prison.

It was during this last tenure in prison that Meherally suffered a debilitating heart attack. The prison authorities offered to shift him to St George Hospital for special treatment but the principled man demanded that two other ailing freedom fighters should also get the same facilities. When the authorities refused, he chose to remain in prison.

Over the following few months, freedom fighters across India responded with waves of civic rebellion despite the violent backlash from the British authorities. While the Quit India Movement did not result in immediate attainment of freedom, it did indeed create the massive pressure that resulted in India bidding farewell to the British just three years later.

By the time he was released in 1943, Meherally’s health had deteriorated sharply but he continued to contribute to the cause of Indian independence. The selfless leader was over the moon when his beloved motherland finally unshackled the chains of colonialism and awoke to freedom on August 15, 1947.

However, the years of struggle had taken its toll, rendering him weak and bed-ridden, though only physically and not in spirit. Even from his hospital bed, he continued to work to highlight India’s vibrant diversity and rich heritage.

In October 1949, Meherally organised a one-of-its-kind exhibition that displayed more than 200 pictures and paintings that traced the evolution of India’s freedom struggle since 1857. He also organised several cultural and literary events at Bombay’s famed Kala Ghoda, inviting Indian personalities who were legends in their respective fields.

On July 2, 1950, Yusuf Meherally passed away at the age of 47, his death rousing the same passion in the public as his slogans. Shocked at the loss of their beloved leader, all of Bombay was in collective mourning. The next day, as the clock struck noon, buses, trams and trains across the city stopped for a few minutes.

Almost all schools, colleges, shops, factories and mills remained shut. The Bombay Stock Exchange, an iconic symbol of the city’s financial strength, witnessed no trading though officially open for business. The city that never stopped, Bombay stood still in the memory of the man who had literally given his lifeblood for the city’s well-being and the country’s cause.

source: http://www.thebetterindia.com / The Better India / Home> Freedom Fighter> History> Lede / by Sanchari Pai / September 28th, 2017

Bombay (Mumbai), MAHARASHTRA :

IN 1942, a daughter was born to Fathema Ismail, the sister of cotton king and Congress financier Umar Sobhani, and Mohammad Hasham Ismail, a government of India trade commissioner posted in Mombasa. She was fondly named Usha – after the Goddess of dawn – in the expectation of a new dawn as the city and the country was immersed in the Quit India movement. Fathema Ismail was closely involved with Kulsum Sayani (the mother of Ameen Sayani) in women’s education and the establishment of All India Village Industries Association. When Usha turned three the family discovered that she had polio.

“Amma was dejected with the news, but at the same time she was determined to get the best treatment for me,” recalls Usha Cunningham who is now based in New York. She recalls the turbulent years where India fought and finally achieved freedom from the British, which ran parallel to her own fight with polio. Patel Manzil at Nepean Sea Road, where Usha grew up was a safe haven for underground activists. “Aruna khaala (Aruna Asaf Ali) and other leaders would live under assumed names in our house. My mother’s nationalist leanings were well-known but as my father was a trade commissioner, we escaped scrutiny.”

In her search for a doctor, Fathema was referred to Dr M G Kini, an orthopaedic surgeon based in Madras. “Dr Kini was a crusty, old man who first declined to accept my case. Amma would literally sit outside his residence and accost him in the morning, afternoon and evening when he would travel between his house and clinic. He ultimately agreed and we stayed in Madras for around eight months,” recalls Cunningham. Under Dr Kini’s guidance Usha showed tremendous improvement.

The Madras visit also marked the beginning of Fathema’s discovery about the lack of facilities for children afflicted with polio. Soon her husband Mohammad was transferred to Iran from Mombasa, but she stayed in India. After Madras, the next stop was Pune, where, Fathema had gathered, there were some facilities for rehabilitating injured soldiers at the British Army Hospital. “There were three British physiotherapists who would treat the injured soldiers with the help of a few trained Indian assistants. Amma requested similar training and after some reluctance was allowed access,” remembers Cunningham.

What worked in her favour was the fact that Fathema had gone to Vienna to study medicine in 1920 after finishing her schooling, but had to return due to a financial crisis in the family. For three years she had stayed alone in Vienna absorbed in her studies. Decades later, those three years of study helped facilitate a better understanding of the process of rehabilitation. More than two years of treatment and therapy changed Cunningham’s life. From “totally paralysed”, she regained remarkable mobility in her right leg. Little did she know that she would soon become an exemplar of how patients with polio need not be confined within the walls of their house – ignored and neglected.

Fathema was now determined to start a facility for the countless poliostricken children and their parents. Her experience and observation in Madras and Pune gave her the confidence to start a clinic in Bombay (as it was known then). But finding a suitable space amidst a financial crunch plus low awareness of the disease were formidable hurdles. She also had to ensure she had enough medical equipment to attend to the children. The war had ended and the imminent departure of the British meant that the Army hospital in Pune faced an uncertain future.

In 1946 she had established the Society for the Rehabilitation of Crippled Children (SRCC) but despite her pleadings, the hospital was not willing to share or sell the equipment. She then convinced two of the Indian assistants to get the various equipment and kits transferred to Bombay while the hospital was winding up. “She promised them jobs and convinced them of the immense good this would do for the poor patients,” recalls Cunningham, the excitement in her voice palpable as she recounted her mother’s exploits.” Not many people know that six truckloads of machinery were taken out from Pune,” she says.

These surreptitiously transported kits formed the base for a polio clinic that was opened in May 1947 in the empty Chowpatti premises offered by Dr A V Baliga, who was going to the United States on a study tour. After few months the Bombay government gave space in the empty barracks at Marine Drive as the clinic’s immense popularity led to a waiting list. In the wake of Independence, Bombay and India, had woken up to the need of rehabilitating the differentlyabled. Medical journals and international aid organisations took note of Fathema Ismail’s enterprise.

In 1951, she visited the United States on the state department’s invitation for a four-month tour of various hospitals, and the same year went to Europe to attend international conferences. She was now determined to open a full-fledged hospital. “She caused quite a headache to Prime Minister Nehru as she demanded a plot near the race course at Haji Ali. It was a prime location and Nehru would say ‘Fati, why only that plot? I can request the Bombay government to give some other place’. But Amma was insistent. The racecourse was frequented by the rich and the famous and one of the reasons for the request was that she wanted larger society to be fully aware and responsive to the problem of polio.”

The result was a children’s orthopaedic hospital, which opened in 1952 and was inaugurated by Nehru, which continues to operate to this day. After roughly 30 surgeries and years of therapy, Cunningham who is now 75 years old, has no regrets. “I have climbed mountains, ran a business in Delhi, shifted to America, got married, have a caring husband and daughter. This is what Amma wanted. Similarly she convinced several industrialists to offer training for the handicapped at her centres so that they could get employment.” In 2011, India announced that it had eradicated polio but the foundation stone for this incredible campaign was laid by a lady who had the grit and determination to envision a polio-free society over 70 years ago.

source: http://www.ahmedabadmirror.indiatimes.com / Ahmedabad Mirror / Home> Others> Sunday Read / by Danish Khan, Ahmedabad Mirror / August 20th, 2017

Bhopal, MADHYA PRADESH :

Bhopal :

Centered on the life of freedom fighter Maulana Barkatullah Bhopali, a play ‘Baghi Banjara’ was staged at Shaheed Bhawan on Friday. Scripted and directed by Waseem Khan, the play was staged for the first time in the country.

Abdul Hafiz Mohamed Barakatullah, known with his honorific Maulana Barkatullah (7 July, 1854-20 September 1927), was an anti-British Indian revolutionary with sympathy for the Pan-Islamic movement.

The whole journey from birth to death of the great freedom fighter was beautifully shown in the one-hour-twenty-minute-long play. Barkatullah was born on 7 July 1854 at Itwara in Bhopal.

He fought from outside India, with fiery speeches and revolutionary writings in leading newspapers, for the independence of India. In 1988, Bhopal University was renamed Barkatullah University in his honour. He was educated from primary to college level at Bhopal.

Later he went to Bombay and London for his higher education. He was a meritorious scholar and mastered seven languages: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Turkish, English, German, and Japanese. Despite a poor background he topped the list of successful candidates in most of the examinations for which he appeared, both in India and England. He became the Quondam Professor of Urdu at the Tokyo University Japan.

He was one of the founders of the “Ghadar” (Rebellion) Party in 1913 at San Francisco. Later he became the prime minister of the Provisional Government of India established on 1 December 1915 in Kabul with Raja Mahendra Pratap as its president. He died in 1927 at San Francisco.

The play was presented by mainly young cast of Swabhiman Shikshan Samiti. Suggestive sets, costumes and lights were used.

A patriotic song ‘rang de basanti chola…,’ of movie ‘Shaheed’ (1965) was used in the play. Gaurav Jaat as Maulana Barkatullah, Badra Wasti as Tarik Nigar, Shakeel Chand as Kadar and others were in lead role.

“For the first time, the play centered on the great freedom fighter is being staged for the first time in India. I don’t know why no play was staged on the tenacious fighter. I wrote the play at the instance of Shriram Tiwari, former director of culture. The writing took one year and the rehearsals lasted for one-and-a-half- months,” said Waseem Khan.

source: http://www.freepressjournal.in / The Free Press Journal / Home> Bhopal / by A Staff Reporter / January 28th, 2017

SINGAPORE :

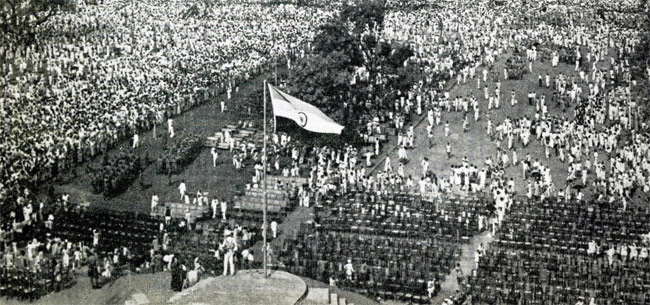

On August 4, 1914, the British Empire declared war on Germany, making WWI a truly global war. As Britain observes the centenary of the war on Monday, TOI takes a look at one episode of 1915 that rattled Britain and her empire.

On February 15, 1915, the 5th Light Infantry Regiment of the Indian Army was getting ready to embark on a voyage to Hong Kong from Singapore. A little after 3pm, one sepoy Ismail Khan of C company fired at an ammunition lorry from the quarter guard near Alexandra Barracks. Soon, sepoys and VCOs (viceroy’s commissioned officers) of four predominantly Muslim Rajput companies (there were some Jats and Lohias too from Haryana and Punjab) of the eight-company strong regiment mutinied, starting a week of chaos and bloodshed that has come to be known in history as the Singapore Mutiny.

A lot has been written about the mutiny ever since, but very few have been works of scholarship. Fewer still are the official histories of the event. But in India, there’s a great deal of mystique surrounding this episode, which nationalists, historians and others, have linked to the freedom movement. They see some commonality between the 1857 Uprising and this one, and glorify this mutiny, without, of course, considering what the main actors of the event, the rebel sepoys, said in their testimonies to the courts of inquiry.

They gave ambivalent statements, turned coats, played victims, and testified against men already dead in the mutiny or executed by firing squads. They did all this to exonerate themselves and men of their own caste/village from swift colonial justice. Even those sepoys who were identified as mutineers by others spun convincing tales to fool the court.

The Times of India had extensively reported the mutiny in 1915, calling it the Singapore Emeute. On March 2 that year, when the mutiny had already been put down and the inquiry was on, the first news of the mutiny had reached India. This paper had reported then: “A serious emeute has occurred among the 5th Light Infantry. One wing mutinied and killed Europeans on the road. The situation is now in hand. A large number of the other wing are coming and offering assistance.”

The mutineers belonged to the right wing of the regiment. The left was primarily composed of Pathans (the sepoys, though, called themselves Hindustani Pathans) who also came from the same regions as the Muslim Rajputs—Punjab and Haryana, including areas that form part of Delhi NCR today. These men didn’t join the mutineers, but ran helter-skelter in the melee and shut themselves in bathrooms/toilets and shops, with many escaping to the forest.

It was a deja vu moment for the regiment, which, in its previous avatar as the 42nd Bengal Native Infantry regiment, had seen exactly four companies rebel during the 1857 Uprising and the rest staying loyal. That was the reason why the regiment wasn’t disbanded after the Uprising was quelled. In 1915, too, the regiment would escape disbandment because of this reason, and would “honourably discharge its duty and salvage its lost reputation” in East Africa where they would fight the Germans.

But in the week that the mutiny lasted, the rebels killed 12 British officers and 14 European civilians, liberated German prisoners held in a jail (of whom 17 joined them and the rest stayed neutral), and got on board by persuasion or intimidation some men of the Malay States Guides.

On March 3, 1915, The Times of India had a clearer picture of the mutiny. “Further facts regarding the outbreak at Singapore have now come to hand which leave no doubt as to its serious character. The reasons for the disturbance are still somewhat obscure, but the trouble would seem to have originated in some discontent aroused in the 5th Light Infantry by certain promotions among the Indian ranks. This appears to have engendered the spirit of disaffection which was brought to a head by the impending departure of the regiment for Hong Kong. It is satisfactory to be able to record that even not more than half of the 5th Light Infantry, a regiment with a distinguished record of loyal service, were implicated,” TOI had reported.

That obscurity, as stated in the TOI report, has remained till date. The mutiny was quelled by the British by February 22 with Franco-Russo-Japanese help. After that, it was the time for conspiracy theories. Though there was little evidence on ground, the mutiny was linked to the Ghadar Conspiracy—efforts by the Ghadar Party to foment rebellion among Indian troops stationed abroad. The Ghadarites themselves took credit for it, though they got news of the mutiny only on March 2—the same day TOI carried the report—after the mutiny was suppressed. And they thought until April that Singapore was under rebel control.

Then there was the German conspiracy theory. At least one German prisoner took credit for inciting the Indian soldiers to mutiny. Plus the sepoys are believed to have received letters from their comrades fighting in Europe that the German king had converted to Islam and that it was not right to fight the forces of a Muslim king.

Then there was the more convincing theory of the sepoys rebelling due to their unwillingness to fight the forces of the Ottoman Sultan, the caliph of Islam.

But the real factor may have been a combination of terrible lapse in communication and leadership on the part of the British (the CO of the regiment was particularly unpopular among the troops and officers, both Indian and British. After the mutiny, he was dismissed from his post and retired from the Army) and a greater desire among the Indian troops to escape the horrors of European war—the latter observation also made by Japanese historian Sho Kuwajima.

On July 5, 1915, TOI carried the government’s explanation: “In view of the misrepresentations that have been made regarding the mutiny, we are authorized by the governor to state that no report whatever had reached His Excellency or the general officer commanding prior to the mutiny regarding any seditious tendencies in the 5th Native Light Infantry … No charge of disloyalty had ever been made to the government against the 5th Light Infantry … on the other hand, Government had received most positive assurances as to the loyalty of the regiment.”

Yet the sepoys were only loyal to one another in their regiments, battalions and companies as in the case of the Singapore mutineers. They gave no call for freedom or anything of that nature.

Nevertheless, in the immediate aftermath, there was disturbing talk about the loyalty of Indian troops, and the wisdom of trusting the security of big colonial possessions like Singapore to Indians was questioned too. But in a strange coincidence, exactly 27 years after the Singapore Mutiny, on February 15, 1942, 80,000 British-led Allied troops surrendered at Singapore to the Japanese of whom 40,000 were men of the Indian Army. Nearly 30,000 of them would eventually join (either voluntarily or under duress) the Indian National Army.

Buried in history

· 47 sepoys, NCOs and VCOs were executed after a general court martial

· The ringleaders were identified as Subedar Dunde Khan, Jemadar Chisti Khan, Havildar Rahmat Ali, Sepoy Hakim Ali and Havildar Abdul Ghani; Dunde Khan and Chisti Khan were shot first on February 21

· 64 others were sentenced to transportation for life or ‘sazaa-e-kalapani’

· No memorial or plaque whatsoever to the mutineers exist anywhere

· Mutineers till today are unfairly vilified in Western accounts

· Since most sepoys on trial and during court of inquiry clammed up, the full truth about the causes of the mutiny are not known till today

(Write to the author at manimugdha.sharma@timesgroup.com)

source: http://www.timesofindia.inditimes.com / The Times of India / News Home> India / by Manimugdha S. Sharma / TNN / August 03rd, 2014

Dipatoli (Ranchi), JHARKHAND :

Jharkhand’s “stepmotherly attitude” towards the mausoleum of Sir Ali Imam, one of Bihar’s prime architects, has prompted the knight’s grandson to resurrect his decade-old heritage status demand for the site that rightly deserves conservation.

In 2005, a memorandum had been signed between the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach) and Birla Institute of Technology (BIT), Mesra, to develop the mausoleum on NH-33 near Dipatoli, Ranchi, into an art and culture centre. But, like most other projects in the state, it sank into oblivion.

In 2012-13, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) listed some monuments for protection, including the Jami Masjid and Baradwari Masjid in Rajmahal, Khekparta temple in Lohardaga and Buddhist ruins in Benisagar, West Singhbhum, but the mausoleum was again given the pass.

Such “monumental neglect” has now prompted Askari Imam, the grandson of Sir Ali Imam, and other members of the Sir Ali Imam Trust like grandnephew Bullu Imam to request the Raghubar Das government for a heritage tag.

Justin Imam, the great grandson of the knight, said they were pursuing the matter with the department of art and culture (archaeology) so that a pending report advocating conservation rights for the mausoleum was given active consideration. “A year ago, we had submitted the report to the department. It is obvious no one took interest. We will push the matter again tomorrow (Tuesday),” Justin said.

Former state convener of Intach Shree Deo Singh conceded that Askari Imam had approached him with a conservation request five years ago. “The Trust was then formed for its maintenance. However, after my term as convener ended, the tomb was subjected to utter neglect,” Singh said.

Bullu Imam pointed out that the monument existed in a capital city and yet most people of Jharkhand were unaware of it. “This is so unfortunate,” he said.

“Once the mausoleum is declared a protected site, it will attract tourists from the state and outside,” added voluntary caretaker Chetan who also runs a shop nearby.

State art and culture secretary Vandana Dadel said members of Sir Ali Imam Trust had met her last week and she had assured them that she would look into the matter. “I will send a team to the site so that we can initiate talks with the ASI,” she promised.

Ali Imam, a judge at Patna High Court in 1917, was a law member of the British Imperial Council and was conferred knighthood by the British government. Sir Ali Imam, who played an important part in the constitution of Bihar, died in 1932 after which the mausoleum was built.

_____________________________________________

Correction:

I would like you to make amendment in one of the paragraph. Where you mentioned that Justin Imam the great grandson to Sir Syed Ali Imam. In fact Justin Imam is the great grandson to Sir Hasan Imam who was the younger brother to Sir Syed Ali Imam Saheb.

Sir Ali Imam Saheb great grandchildren are from Late Justice Jafer Imam, Reza Imam and Naqi. Kindly amend the paragraph in your article.

Many thanks

Amina Imam Ahmad / 05th April 2018

__________________________________________

source: http://www.telegraphindia.com / The Telegraph, Calcutta,India / Front Page> Jharkhand> Story / by Arti S. Sahuliyar / March 10th, 2015