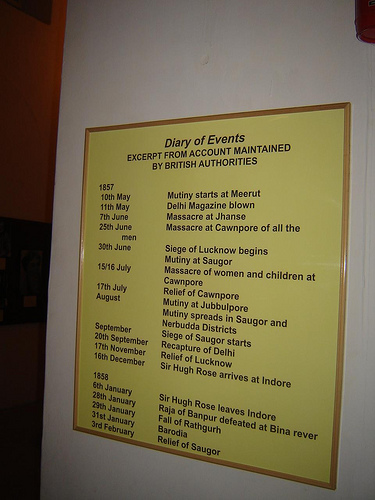

Bijnor, Rohilkhand (Mughal Empire) / BRITISH INDIA :

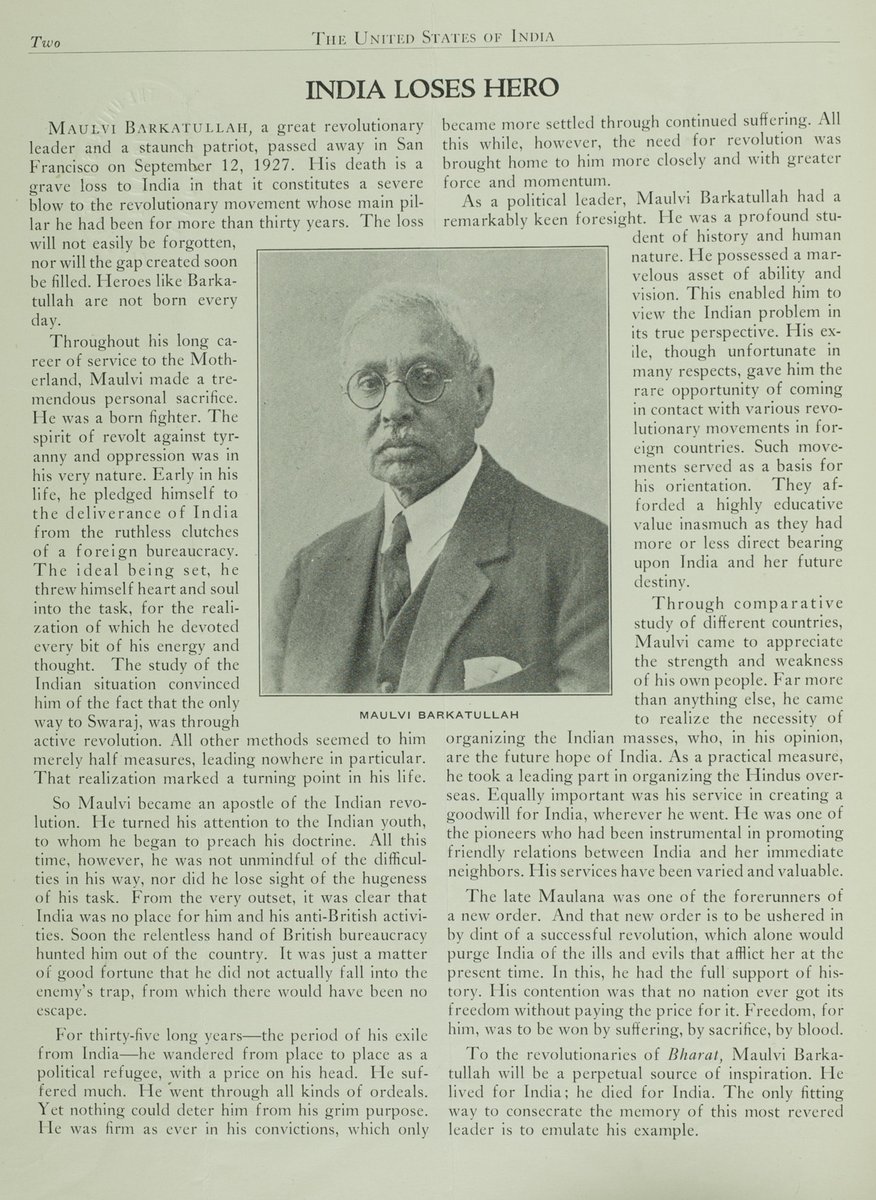

On India’s independence day we remember a forgotten hero from our history

Bakht Khan: Winner of a lost battle

Second of July 1857, a hot humid day some one hundred and fifty-five summers ago, a contingent of about 250 men in their Bareilly regiment uniforms arrives in Dilli of the time, the world renowned Red Fort to be precise. Mounted on their horses, they march past the Laal Purdah [1][entrance to the private chambers of the last Mughal King]. The General of the regiment marches too albeit without the customary bowing down of his head; much to the outrage of those present at the court. But what happens next would seem rather more sacrilegious. That unbending commander of the arriving regiment, a tall and corpulent man of Rohilla stock appears least caring about the sensation he creates and the protest that comes his way, he moves forward and ‘salaams’ the King as if he is an equal.[2] But the King, Zille Sub-haani, Khaleefatur Rehmani, Khudawand e Majaazi, Hazrat Abul Zafar Sirajuddin Bahadur Shah Zafar is helpless.

The man in the eye of this little storm was General Bakht Khan, Commander of the Neemuch brigade, of the Army of East India Company, among the true heroes of 1857, who had arrived to make a fight against the Company which till now he had served.

He was described as “a much garlanded and battle hardened veteran of Afghan wars, with huge handlebar moustache and sprouting sideburns…. Known personally to several of the British officers” [3] His reputation as an able administrator and a shrewd military strategist had reached Delhi much before his arrival.

The poor Mughal King, after much reluctance, decides to award the just landed General ,a royal sword and a buckle but Bakht Khan still refuses to present the ‘nazar’ (a mandatory monetary gift to be offered to the King) when meeting him. Soon after, this Khan then begins to give a piece of his mind to the king, he begins, “Your good for nothing princes [sons] enjoy full powers over your military. Give all the power to me as no one else but I know the norms of the English army, who knows them better than me?” This was blunt and undiplomatic at its best, but the man in question, meant business. He was duly appointed the Governor General of the army, effectively displacing Mirza Mughal the headstrong son of Zafar.

Reading literature about 1857 revolution became quite an obsession with me since a teenager, our shared history of the sub-continent, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A familiar heritage we possess, a common thread running through our past. History is journalism with hindsight and this special journalism about 1857 period transports us to a novel world inducing in us a sense of déjà vu. It was through these readings that I ‘discovered,/em>’ Bakht Khan. But it was not love at first sight; I must tell you, what with his being a man with a pot belly that did not make him a fine horseman! Add to it the derision he was subjected to contemptuously for the reason of his being a Wahabi. But more surprising were the contradictions that I began noticing in various descriptions about him. A few, mostly historians from the east, respected him as one of the bravest soldiers and the real hero of 1857 Ghadar while the rest seem to scorn him just for being a Wahabi. This term in itself is quite controversial, even today, just as it was in those days.

Wahabism is the name given to Islamic philosophy instituted by Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahab Najdi[1703-1792] in 7th Century Arabia; the intention was to practice Islam it in its purity just as Prophet Muhommad (peace be upon him) did. William Dalrymple elaborates General Bakht Khan‘s Wahabism thus, “Like a Wahabi ,” he says, “Bakht Khan disdained earthly rulers, whom he regarded as unIslamic, and longed instead for a properly Islamic regime.” [4] He cites his Wahabist thoughts to be a cause of his failure. Interestingly , Bakht Khan fought under a king who was the embodiment of everything a true Wahabi abhors.

What is astonishing is that in almost every account about the man, his being a Wahabi is essentially stressed, perhaps to draw attention to his real or imagined fanaticism. Some of the earlier prominent revolutionary figures like Syed Ahmed Shaheed and Shah Ismaeel Shaheed were self-proclaimed Wahabis. Let’s see what Bakht Khan‘s Wahabism was like.

His Wahabism was said to have been inspired by his spiritual mentor, Moulvi Srafaraz Ali, a master teacher of Algebra and Geometry and with a thorough knowledge of Tafseer[Quranic interpretations] and Hadeeth [Prophet Muhammad‘s sayings]. Moulvi Sarfaraz Ali was entitled as Imam of Mujahideen and his orations exhorted people to join this revolution. It was he who had motivated his initially reluctant disciple Bakht Khan to join this momentous struggle. In the pre- revolution time, Moulvi Sarfaraz Ali was regarded as one of the brightest jewels in Delhi’s intellectual crown, by no less than Sir Sayyed Ahmad Khan himself. So it was Moulvi Sarfaraz Ali who urged Bakht Khan to fight against the infidel Christians for the honor of his country. Interestingly this ‘accusation’ of his being a Wahabi also betrays probable renaissance Islamic nature of the revolution of 1857.

Being a Wahabi, Bakht Khan was against the veneration of Sufi shrines, which was/is quite a rampant practice among a large section of the Indian Muslims. The Wahabis disapprove of it as being nearer to idol worship and a tendency picked up from their Hindu brothers. What is important to be noted and not to be overlooked is; this Wahabism of Bakht Khan and his mentor Moulvi Sarfaraz Ali was borrowed not from Abdul Wahab Najdi of Saudi Arab but from Shah Waliullah Muhaddith Dehalvi [1703-1762], the father of Islamic reform movement in India. This reform movement aimed at eliminating all non-Islamic innovations and practices from the religion and restoring a strict Islamic monotheism, among Indian Muslims. Shah Waliullah, was the first one to translate Quran into Persian and anticipated many modern, social, economic and political thoughts, such as social reform, equal rights, labour protection, and welfare entitlement of all.

My attempt here is to present a brief sketch of this Great General as a figure who, till his last struggled for the dream of a Free and Unified India where harmony among the different ethnic groups was his top priority.

His Origins:

Bakht Khan was of Rohilla [Afghan] stock. His grandfather Ghulam Qadir Khan came to Lucknow to make a living. His father Abdullah Khan, said to be a very handsome man, was married to an Awadh Princess. Bakht Khan was formerly a Subedar in the 8th Foot Artillery at Bareilly and had served the British for over forty years and fought bravely in Afghan wars. He had progressed quite rapidly and was appointed in a high-ranking position there. Interesting to note, is his close friendship with many British officers, under whom he had served and imbibed the art of war. Colonel George Bourcheir was educated in Persian by him, and who describes his tutor as, “very fond of English society …..[and] a most intelligent character.”[9] But quite a few disagreed and called him, a fat guy, socially ambitious and an incompetent horseman, probably the worst insult for a soldier, in those times. His commanding officer, Captain Waddy [BHA], describes him thus, “ He is sixty years of age and is said to have served the Company for forty years; his height 5 feet 10 inches; 44 inches round the chest ; a very bad rider owing to a large stomach and thick thighs but clever and a good drill” [10] When the revolution began he was already in his native town of Bareilly and his fame as a fine administrator and a brave and especially able army commander had spread in the country. He had arrived in Delhi with a huge contingent of 7000 [according to another source, 14000] cavalry and hundreds of infantry and a treasure from Bareilly.

Bakht Khan as an Administrator:

It is indeed quite fascinating to know Bakht Khan’s efforts in trying to enforce some kind of sense and sensibility, onto the madness of loot, plunder and sheer chaos of the Delhi of 1857 uprising. He tried every trick in the book to restore law and order amid that disturbing pandemonium .Munshi Jeevan Lal, [11] the overweight Mir Munshi [Chief Assistant] of Resident of Delhi, Sir Thomas Metcalfe [who was working as a British spy, describes how General Bakht Khan went about restoring order amidst that unprecedented anarchy spread after the arrival of the rebels, in the capital. It’s a human thing to love admiration; but when it comes from the enemy, it becomes doubly significant.

Munshi Jiwan Lal in the notes to his British Masters appreciates measures taken by Bakht Khan. There were to be no taxes on salt and sugar, looting [by the just arrived rebel soldiers]had to be stopped else their plundering hands would be cut off, shopkeepers were to be given full protection and even encouraged to use weapons[if they had none, then would be duly provided from the state armory], soldiers were to be removed from the Dilli bazaars as it created difficulties for the general public and relocated in camps outside Delhi gate, their salaries were to be restored and promises of jagirs were made to them in return of their services to the army. He further informs that the General’s men had also killed three spies working for the British [M.Baqar Ali, father of Muhammad Husain Azad, the famous Urdu writer, too, had complained in his first report that, he is followed by the spies of Bakht Khan wherever he goes,[12]

The Metcalfe’s Munshi tells his masters that General Bakht Khan was soft spoken to his men but also remained firm that, they should not cross their line of duty even in the smallest measure. Impressive army parades were conducted by him from Delhi Gate to Ajmeri Gate. Many important petitions from various kings, Nawabs, Rajas, and officials of courts, were forwarded to the King and replies were received through the office of Governor General Bakht Khan; chief among them were, Qudratulla Khan, Risaldar of Awadh, Khan Bahdur Khan, Rao Tula Ram. A ruqqah was also addressed to the Patiala Rajah, conveying pardon of the King for his faults, many other such instances of accessing the King through the General can be found in different accounts of history. [13] Here he was playing the role of a keen diplomat. His honest and sincere attempts at running the administrative affairs efficiently at court and his diplomacy with the men of importance are discernible from these accounts. The steps he took to restore a sense of sanity in those insane times are evidently commendable but somehow go unnoticed by his critics.

Bakht Khan as a military strategist:

The General was a shrewd military strategist. What he achieved at the battle field of Delhi becomes more significant considering the dire circumstances he worked in. He had little support from his own army factions and was constantly attacked and maligned by some hostile elements from within. His strategies on the battle field, his trying to sabotage the passages that took supplies to their camp, invention of rota system and his playing the mind games with the enemy, all are indeed splendid. Richard Barter gives tribute to this great man thus: “Thanks to the system organized by Bakht Khan…..We were scarcely able to stand….” [14] He was speaking, worn out at the battle ground along with his soldiers, thanks to the new General’s machinations. Their frustration grew to the extent that some of the British soldiers seeing no sign of relief wanted to kill themselves on purpose, and some even did.

Be it propelling a contingent to Alipore or setting up a new rota system intended to engage the British forces on a daily basis, and which meant leaving them no respite from the combat, General Bakht Khan always worked on new strategies to defeat his enemy. Soon after his arrival, on the ninth of July he made a massive attempt to destroy the British forces and one of his strategies was to clothe his men in British white uniforms. This took the opponents by surprise and a deep access was gained into their camp. Such regular expeditions by Bakht Khan frustrated the enemy to the extent that, they began losing all hope of capturing Delhi again. He succeeded as he knew the British tactics inside out .His long service to them had at last, paid off.

Bakht Khan informed the king that Prince Khizar and others were stashing away the taxes collected from the city traders and due to this salaries of the army could not be paid. Prince Khizar was asked to return the booty. The commoners were pleased with him while the Mughal princes vowed vengeance. Undoubtedly Bakht Khan was a man of the world but he was not at all, worldly. He frequently failed to decipher his detractor’s nasty plans and eventually became a victim to their malice.

The Neemuch brigade-his force- was well-known for its valor; but the two of its generals Ghaus Khan and General Sidhari Singh [supporter of Mirza Mughal] parted ways, from Bakht Khan, as they couldn’t digest the fact that, an officer of the similar rank as theirs should get so much importance from the King. During the battles he was left alone to fend for himself. A most ridiculous charge of his being a British spy also came along. All this put him under great pressure and he had to issue a statement denying all these charges. Whether it was failure to capture the army bastions at Alipur, Manali Bridges and the Ridge and almost all the failures were wrongly attributed to the General. Zafar too now was infected with doubt and the devious designs of his foes resulted in Bakht Khan’s removal as Governor General by the end of July. A Court of Administration was established to run the affairs of the Mughal Darbar. The General and his Bareilly brigade kept their distance from it but their assaults grew weaker and the tremendous pressure that he was able to put on the British began to diminish. Dalrymple remarks, “…the end of Bakht Khan’s military system brought instant relief to the British on the ridge”. [16]. It is indeed saddening that such lowly games of selfishness and rivalry did the good General in and ultimately caused the struggle for freedom, a catastrophic damage, giving a boost to the enemy. Richard Barter joyously announced that, “And so, when we were scarcely able to stand, the attacks ceased, as if by a dispensation of Providence, and gave our force the repose they so much needed.”[17]. The one man who possessed the potential for defeating the enemy was thus, rendered impotent.

As no intelligence about the success of the good General’s methods reached the court and Delhites, it led to huge misgivings about his military forays. Resentments, against this good soldier soon began to build up. As mentioned earlier, he was accused of being a British stooge himself. His own colleague from the Neemuch Brigade Sidhari Singh accused him thus. Other former co-workers too were not far behind. Gauri Shankar [who was himself a British spy] and Talyar Khan, on 20th August, arranged for a Sikh to proclaim that Bakht Khan provides all information about the court happenings to the enemy. But the truth was found out and the witness was rejected for his false claims. The General himself issued a public statement denying this in the presence of Mirza Mughal and other army generals.

The ever eternal quintessential factors of jealousy envy and contempt did this great warrior in. Quite perceptibly his disenchantment began to grow. He became more cautious but continued to be at the forefront of the war and the biggest headache for the British. He marched towards Najaf Garh separate from the Neemuch brigade as his own soldiers refused to take orders from him (and resultantly was smashed by their rivals). Like before, the General was unjustly blamed for this fiasco, as well. Nevertheless Bakht Khan still remained defiant. He was unrelenting and rejected Zafar’s suggestion of opening the gates of Delhi, if the British could not be defeated. He elaborated on some new strategies and it was quickly reported by the spies present at the court to the Gora Sahibs. Needless to add this rendered his plans useless. His failures thus began mounting up. Yet he succeeded in defeating the opponents at the Delhi Gate even in those final hours, and kept a strong vigil at the Ajmeri Gate till the last moments of the war.

Despite his failures, more due to the non co-operation of his team than his own faults, what he did achieve was the delay in recapturing of Delhi by the British, as long as he could. The erstwhile Dilli would have been rounded up, quite early in the day, had it not been for the efforts of General Bakht Khan Rohilla.

Memorial for British soldiers at Delhi Ridge. No memorial for Indian soldiers though.

His military achievements despite the hostilities he faced were amazing; be it capturing three hundreds of British horses taking supplies to their masters, or one of his final determined attacks with his Bareilly and Neemuch troops, which forced the British to make a hasty retreat, from Hindu Rao’s house. Bakht Khan’s advance up to the house of Hindu Rao was no mean achievement; it threatened to cut off the British troops from their camp.[18] Had he been supported efficiently by his own people at the time, his success rate would have been much higher. Miyan Muhommad Shafi , in his famous work, Pehli Jang-e-Azadi-Waaqeyaat wa Haqaayeq, blames this sorry state of affairs on the conspiracies hatched against Bakht Khan by the unfortunate and unreasonable Mughal Princes, who conspired against him, unaware of their approaching terrible end. He says, “The courtiers created havoc each and every time and put blame on him for everything going wrong, without providing him with any kind of general support. All this and the corruption at the court and among the army rank and noncompliance of the troops, disheartened this most able of the fighters, Bakht Khan and after being relieved from his various significant positions , he got reduced to taking care of his own original regiments alone. This turn of events and colossal difference of opinions, among the different elements at the court, led eventually to the downfall of Delhi, the arrest of Zafar and slaughtering of his sons, not to mention hundreds and thousands of Delhites being butchered and displaced, forever.”[19] But in the mayhem of 1857 mutiny what was more tragic perhaps, was the ruin of Shehar e Dilli and its uniquely rich Ganga –Jamuni Tehzeeb. It died forever.

It was but for Bakht Khan‘s efforts that the rebel forces cold hold on for a longer period. It is an irony that they all blamed him; his enemies could be found easily on both sides of the divide. When the scene grew bleaker and the British forces entered the city gates, he continued persuading Zafar to join him in the inevitable retreat as the area outside Delhi was still under the rebel control and help could be at hand. The former Subedar in his last ditch attempt, insisted to Zafar, that, the name and status of Mughal King would surely bring victory to the Indians. Never say die spirit of Bakht Khan is here for all of us to see. The fragile eighty year old King Zafar, last descendant of the Timuri lineage had even agreed initially. But schemers like Hakeem Ahsanullah Khan, the court physician and Mirza Ilahi Bakhsh, father in law of Zafar’s deceased heir Mirza Fakhru, superseded the Khan one more time, eventually leading the last Timur to be a hapless royal British prisoner.

At this juncture, Bakht Khan speculated on the reasons of their defeat. He explicated that, their choosing of Delhi as their bastion of the battle was erroneous from the day one. He also faulted the princes and especially Mirza Mughal who’s imprudent handling of the affairs at the battle field did greater damage to the cause. This Prince was the one who possessed no experience of any war and had taken up the cudgels only for bragging about his bravery.[20]

Bakht Khan’s administrative skills added to his superb military zeal had proved to be a deadly combination for the enemy. Alas, his spirit was broken by his own men and he had to retreat and disappeared. There are different theories about his departure. It is said he went to Awadh and fought against the British, one more time. A few others opine that he was killed in a battle and a few more say he escaped to Nepal, never to be seen again. This last version seems more authentic.

The Hindu-Muslim equation of the time and Bakht Khan’s role in it:

In his legendary fight at Delhi of 1857, Bakht Khan’s zealous efforts at maintaining Hindu-Muslim unity are outstanding. More so as he is accused of being a Wahabi; this becomes doubly significant.

A general peace had always prevailed among the Hindus and Muslims of Delhi. Turmoil seemed to brew when Hindu sepoys killed five butchers for slaughtering some cows. The fear of inter-communal clashes strengthened the already existing general disillusionment among the Delhi masses [especially among the Ashraaf or high class people] about the rebellion and the uncouth rebels, popularly called, Purabiya or Tilanga. The British were sitting with their fingers crossed, hoping for a bloody game to begin on the day of approaching Baqrid. They expected violence, as Muslims would slaughter the cow which would anger Hindus as it is deemed holy in their religion. But to the disappointment of the British, Bahadur Shah Zafar himself assured a group of Hindu generals about his intention of banning the practice of sacrificing a cow, with immediate effect. Bakht Khan through his order of 30th July saw to it that this order was strictly implemented. He thundered that whoever was found guilty of slaughtering cow, ox, or buffalo, would be considered an enemy of the state and of the king respectively, and would be punished with death![21]

He didn’t stop at that. He sent out a written proclamation to Delhi’s Kotwal on 31st July and 2nd of August 1857 to the effect that, every morning and evening, it should be announced to the people that this order against cow slaughter should be strictly followed, and anyone found guilty would be severely punished. He also saw to it that an alleged fanatic Moulvi Muhammad Sayyed found enticing people for jihad was reined in. The restraining of the fanatic elements and banning cow slaughter were big steps towards restoring communal peace and harmony, at the time and proved a great boost to restoring trust. Hindu Muslim enmity had to be avoided at any cost, so as not to allow the enemy to make a profit out of it. Bakht Khan made it the central point of his fight and this is admirable.

However the Good General is also blamed for drawing together Delhi ulemas [supposedly against the wishes of King Zafar ]and making them sign a fatwa to urge the Muslims to fight against the British, taking it to be their religious duty. But it must be noted that, it was a call for a mutual struggle, for the honor of the motherland. Barun De makes a valid point, when he articulates, “All listened to the call of dharma or deen. In this sense, Christianity was the symbol of intrusive colonialism, seen as a bourgeois crusade for market globalization, much as it is being seen by neoconservatives today [22) This was something quite remarkable about the 1857 revolution. We can call it a golden period of proverbial Hindu-Muslim harmony.

1857, Ghadar

Here in lies an amazing story of the people, fighting an enemy hundred times stronger than them. These people were the poor, the workers, the weavers, the peasants; all joined hands together to resist the injustice they were subjected to, since last hundred years or so. More admirable is the fact that, despite huge caste disparities, clan conflicts, geo-ethnic varieties and most of all those bona fide religious differences, Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs became united for the cause of India/Hindostan. Esteemed historian Irfan Habib finds this assimilation exceptional. The astonishing fact, he says is that, “…on many occasions largely Hindu contingents elected Muslim officers and, similarly, contingents with a largely Muslim composition chose Hindus as their officers. The fact that this was not anywhere done consciously makes it a particularly notable example of inter-religious solidarity among the Bengal Army sepoys.” [23]

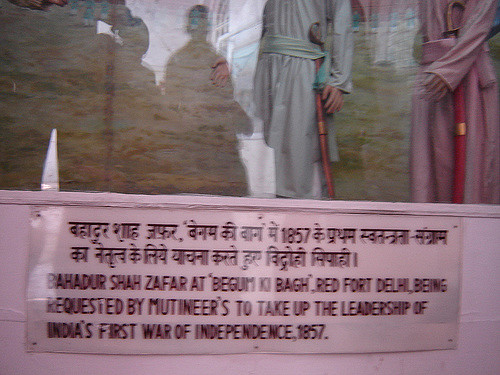

This message of unity in diversity is indeed the most outstanding lesson; we get to learn from 1857 uprising. The little armies from all over India grouping in Delhi to fight under the leadership of a Muslim King, is a grand testimonial in itself. This Muslim King had been a titular figurehead of the erstwhile India, for quite some time, but still thought to be a figure of authority. It was a matter of belief, of faith, for the Indians. They still believed or wished to believe in Bhadur Shah Zafar being Baadshah-e-Hindostan.

At the risk of digression, allow me to drift and explore this phenomenon a bit more. It was a fact that all army contingents, from all over the erstwhile British Raj territories, moved towards Delhi and gathered at the Lal Qilaa to win blessings from a Muslim king. Today this may seem beyond belief but back then, in 1857; it came most naturally to the Indians of the time. William Dalrymple astutely remarks that, “The rip in the closely woven fabric of Delhi’s composite culture, opened in 1857, slowly widened into a great gash, and at Partition in 1947 finally broke into two. As the Indian Muslim elite emigrated en masse to Pakistan, the time would soon come when it would be almost impossible to imagine that Hindu sepoys could ever have rallied to the Red Fort and the standard of a Muslim emperor, joining with their Muslim brothers in an attempt to revive the Mughal Empire.” [24]

It was due to the unmistakable aura that surrounded the Mughal Empire. Bahadur Shah Zafar possessed that unique trait of being a Benevolent Baadshaah who alone had the power of rendering a sense of strong unity among the varied regions and natives of India.

Now coming back to our General, he proved to be a perfect foil to Bahadur Shah Zafar. H.L.O.Garret, keeper of the records of the government of Punjab, in his 1933 account of the rebellion enlightens us that Bahadur Shah Zafar was only a nominal ruler of a dying Delhi; he duly informs, “The actual military operations were directed by Bakht Khan, on whom a royal decree conferred the title of Commander-in –Chief.” [25] C.T. Metcalfe notes that despite Bakht Khan’s removal from his post at the Delhi Durbar, King Zafar trusted him all along and used to urge him to put up a brave fight as before.[26] Bakht Khan’s endeavors in executing the commands of his king at putting up a unified frontagainst the colonizers, is something fascinating. But strangely enough we do not find many mentions to him in our history books.

The year 1857 strikes a resonance in our hearts even after one hundred and fifty five years. We identify with this first war of independence. The Mughal authority had eroded long before this date; but many critics say, what died in 1857 was hope; hope for freedom, for unity. After 1857, India could never be the same again. The unique aura of Mughal Mystique died too in September of 1857. This aura symbolized a most beautiful land, varied and various in so many ways yet presenting an amalgamation so unique so endearingly rich that the world still fails to offer another such prototype. Bahadur Shah Zafar was an unwilling and hesitant hero standing at complete disparity with the General. The General believed in action. It is this action that makes General Bakht Khan Rohilla a True Hero and those among us who wish to dismiss him as just a sundry character, for them let me quote T.S.Eliot here,

They know and do not know, what it is to act or suffer,

They know and do not know, that action is suffering,

And suffering is action.

It is action, our striving for it and the resultant suffering that teaches us the ways of surviving/winning life. It is our action, our Karma that makes our destiny.

In this regard Bakht Khan became a winner of the war, despite losing the battle.

—

Asma Anjum Khan is Assistant Professor of English in Maharashtra

Bibliography:

1-Lal Purdah- the Red colored curtain at the doorway to the Mughal king’s private chambers.

2-Memoirs of Hakeem Ahsanullah Khan-p.8

From:The Last Mughal- William Dalrymple, 284

3-Bourchier, Eight Months,44n],from: The Last Mughal, William Dalrymple,285

4-Ibid-286

5-ibid-285

6-Inquilab 1857, P.C.Joshi, Urdu Translation, pub: Taraqqi Urdu Taraqqi Urdu Bureau ,secondedition1983,105[References]

7-Irfan Habib, History from Below- Frontline, issue dated, June 29,2007,pg.16

8-Baun De ,Frontline issue dated ,June 29,2007,Pg 9 (Scholars Iqbal Husain and Rajat Kanta Roy too endorse his views.)

9-Bourchier-Eight Months,44,[quoted in Last Mughal,285]

10- H.L.O. Garret, The Trial of Bahdur Shah Zafar,King by Committee,8[ quoted in Gimlette’s post script to the Indian Mutiny]

11–Metcalfe,Two Native Narratives, Narrative of Munshi Jeevan Lal

12-William.Dalrymple,The Last Mughal,302

13-H.L.O.Garret, The Trial of Bhadur Shah Zafar, The Physician’s Testimony ,[Hakeem Ahsanullah Khan was the royal physician]

14-Barter Richard, The Siege of Delhi,36, The Last Mughal.

15-William Dalrymple-The Last Mughal,292

16-Ibid,294

17- Barter Richard, The Siege of Delhi ,[from:William.Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, 294]

18-William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal,357

19-Miyan Muhommad Shafi,Pehli Jang e Azadi –Waqyaat wa Haqaayeq,Urdu,288-89, edition,2007

20- Ameer Ahmad Alavi,Bahadur Shah Zafar,[Urdu]Lucknow, 1955,138-9,[ through [P.C.Joshi, Inquilab 1857-112-114,Urdu , ed.1983,Taraqqi Urdu Bureau ]

21-Press List of Mutiny Papers, no.120/143, 7 Zilhaj,21-RY,29 July 1857

and

Press List of Mutiny Papers, no.111,[c] 332,8 Zilhajj 21 –RY,30 July,Spear,pg.207 [from Iqbal Husain]

22-Barun De, The Call of 1857,Frontline ,issue dated, June 29,2007,pg.8-9

23-Irfan Habib, History from below ,Frontline issue dated June 29,2007,pg.14

24-William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, 484

25-H.L.O.Garret, the Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar, King by Committee, 7

26-C.T.Metcalfe, Two Native Narratives of the Mutiny in Delhi,[1974] 213

The following books helped too in making of this essay:

1-1857 ke chashm e deed Halaat[Almaroof Daastaan e Ghadar]-Syed Zaheeruddin Dehalvi.ed:2006

2-The Other Side of Medal by Edward Thompson, translated by Shaikh Hassamuddin, first edition,1982,Urdu Academy New Delhi Publication

3-Bakht Khan [Marathi]–by Iqbal Husain,2008, National Book Trust ,edition 2010]

source: http://www.twocircles.net / TwoCircles.net / Home> Articles / by Asma Khan for TwoCircles.net / August 15th, 2012