MYSORE :

If the sultan of Mysore had had a bit more luck, George Washington might be known as the Haider Ali of North America

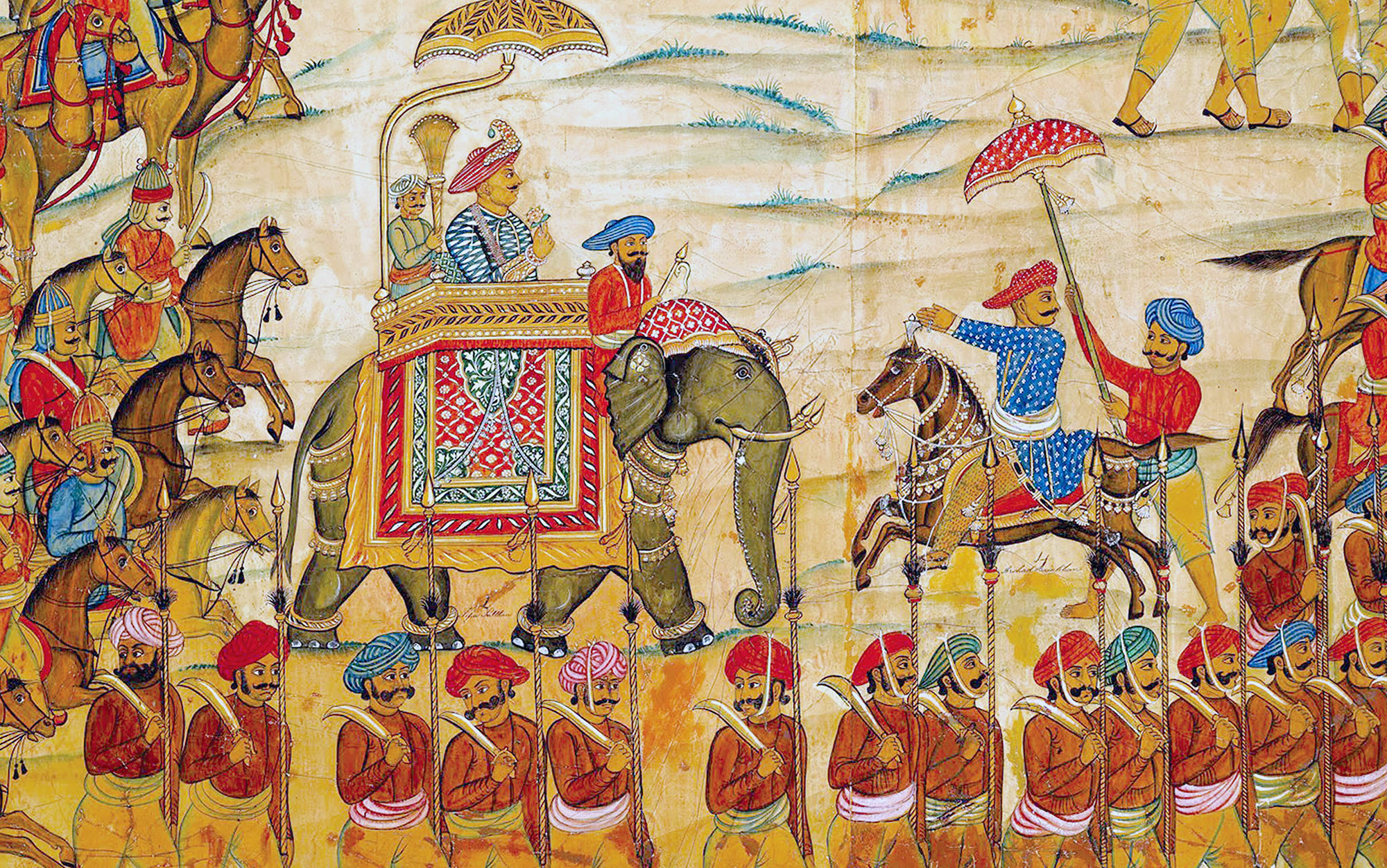

If the sultan of Mysore had had a bit more luck, George Washington might be known as the Haider Ali of North America. As the ruler of Mysore, a kingdom in what is now southwestern India, Haider fought a series of wars with Great Britain in the latter half of the 18th century, at the onset of the Age of Revolution. While Haider was fighting his last battles against the British, Washington was leading the forces of the nascent United States from the harsh winter at Valley Forge to the final victory at Yorktown.

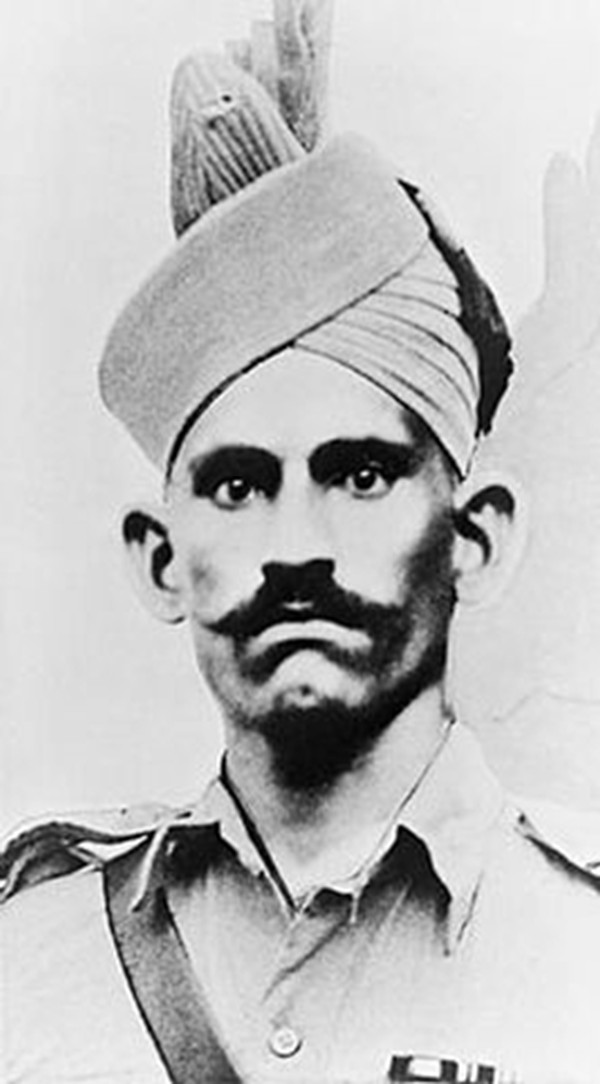

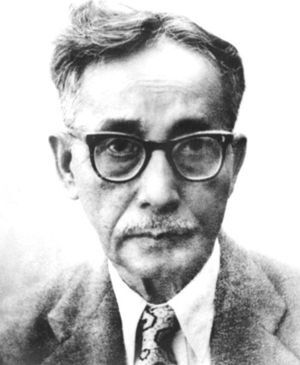

The circumstances of Haider’s childhood did not seem to mark the young man out for greatness. Born around 1720, Haider soon lost his father, a mercenary officer who died on campaign. Haider followed his father’s path, becoming an officer for the Wodeyar dynasty that ruled Mysore. After many years of service, he grew indispensable to the ruling family, sidelining it entirely by the 1760s. It was a dangerous time to come to power in South Asia. The British East India Company was expanding its power throughout the Subcontinent, at the expense of rulers from Bengal in the east to Haider’s neighbours in the south. Allied with France, however, Haider held off the British advance for another two decades, dying in 1782, just a year before the US triumphed in its own rebellion against Britain.

Haider and Washington never communicated directly with one another, but they fought against a common enemy, and shared a common ally. Like the Mysoreans, the American rebels were members of a global coalition funded by the French government, which saw both uprisings as a chance to humble Britain. In the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), Britain had ended nearly a century of conflict with its imperial rival in North America by seizing France’s vast territories in Canada and the Mississippi River Valley. Some French observers tried to minimise the extent of the defeat. Voltaire dismissed loss of North America as ‘a few acres of snow’. Yet French policymakers were well aware that Britain had greatly increased its power. Too weak to confront it again on its own, the French government wove a network of alliances, playing on resentments against Britain’s growing control of global trade and rapidly expanding empire. Beginning in the mid-1770s, it sent money and military advisors to both Mysore and the US, aiming to avenge its defeat by stoking colonial rebellions against Britain.

The alliance with France proved critical to the survival of the fledgling US. The memory of French aid, and particularly of the dashing Marquis de Lafayette’s assistance to Washington, has for more than two centuries served as a symbolic origins story of close Franco-American relations. During the Revolutionary War, however, Americans saw themselves not just as allies of France, but as part of a coalition that included Mysore.

Even after the US made peace with Britain in 1783, the American fascination with Haider and his son and successor, Tipu Sultan (1750-1799) lived on. Mysore’s rulers became familiar references in American newspapers, poems and everyday conversation. Yet, within a generation, Americans lost their sense of solidarity with the Indian Subcontinent. Mysore remained under British control, written out of the story of the American Revolution. The US turned its attention to the interior of North America, and to becoming an imperial power in its own right.

Even before the Revolutionary War, American interest in South Asia was lively. In fact, Americans’ rebellion against Britain in part grew out of the connections between America and the Subcontinent. Before the 1770s, Americans were cheerleaders, rather than critics, of British imperialism. The Philadelphia-born poet Nathaniel Evans (1742-1767) commemorated the victory of the East India Company at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, in which Robert Clive had seized control of Bengal:

The world to British valour yields

How has bold Clive, with martial toil

O’er India born his conqu’ring lance?

Sharing in Britain’s glory in this way seemed natural to Americans, who were proud to be part of the British Empire. The East India Company’s growing influence in Bengal enabled it to export large quantities of South Asian goods, particularly textiles, to American ports such as Boston and Charleston. Colonial elites displayed them in their homes with pride, signs that they were part of a global British empire growing rich from the spoils of the Subcontinent.

While Americans were free to purchase these imperial commodities, they were not free to join British merchants in South Asia. Britain’s colonies served to provide the motherland with raw materials. They were not supposed to have direct economic relations with each other, but rather to send their exports to the great trading centre of London. New England merchants in particular resented being pushed to the side of the mercantile system. Following military victories by the East India Company in South Asia, the company’s economic power within the British Empire, including North America, grew even greater, and so too did New England merchants’ resentment.

In 1773, the British government issued the Tea Act, a bill in effect subsidising the East India Company so it could sell tea to North America more cheaply than any other company. The Tea Act was meant to save the Company’s struggling finances, which were sinking under the cost of its expensive wars. By allowing the Company to sell its tea without paying the heavy taxes normally due on tea exports to the colonies, British officials thought they could help the Company while also keeping Americans happy. Because of the taxes levied on it, tea was expensive in the colonies, and tea-loving New Englanders often resorted to buying theirs on the black market. If the Company no longer had to pay these taxes, it could pass the savings on to thirsty American consumers.

Seeing themselves as victims of Britain’s imperial oppression, Americans sympathised with the empire’s other victims: South Asians

The colonists, however, did not respond as the British expected. By granting the East India Company an exemption from the tax, Parliament had confirmed that the tax on tea, passed without Americans’ consent, was there to stay for all other merchants. And the smugglers that the British government hoped to cut out of the tea business were influential members of New England society. On 16 December 1773, economic self-interest combined with principled opposition to taxation inspired a group of protestors to attack a Company shipment of tea, dumping its contents into the ocean.

The Boston Tea Party marked Americans’ growing opposition to British rule, and the beginning of a new perspective on South Asia. The British government retaliated by stripping Massachusetts of its right to self-government. Outraged colonists met in 1774 to form the First Continental Congress. The following year, armed conflict between colonial militias and British soldiers broke out at Lexington and Concord, and the American Revolution was underway. Americans started to see themselves as victims of Britain’s imperial oppression. They were soon sympathising with the empire’s other victims, particularly South Asians.

The American revolt against Britain quickly took on international dimensions. In 1776, the Continental Congress declared independence, transforming the former British colonies into the United States of America. American agents were soon busy seeking international recognition and goodwill from countries including Morocco, the Netherlands and, most importantly, France, Britain’s imperial rival. Within a year, the French government began sending aid to the fledgling US. A year later, in 1778, France and the US officially became allies.

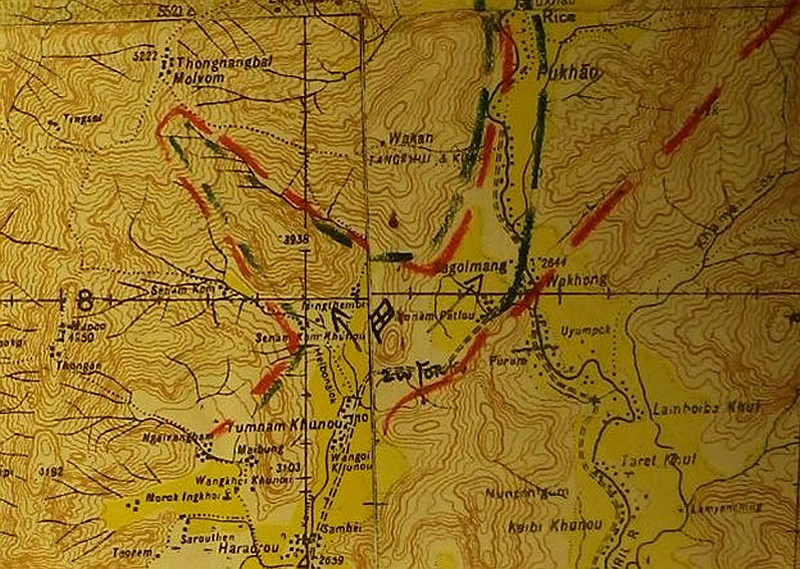

The Continental Congress recognised that it was not France’s only partner against Britain, and looked for ways to cooperate with Mysore, France’s South Asian ally. In 1777, on the advice of Thomas Conway, an Irish-born French military advisor, the American patriots contemplated sending troops to join the French military expedition to the Subcontinent. The provisional American government lacked the resources for such a scheme, so instead it encouraged American privateers to attack the East India Company’s shipping to weaken Britain’s economic grasp on South Asia.

Different state governments also made friendly gestures toward Mysore. In 1781, the Pennsylvania legislature commissioned a warship named theHyder-Ally, an eccentrically spelled tribute to the Sultan of Mysore. This ship sailed the North Atlantic only, far from the Indian Ocean. Its existence, however, demonstrated the affinity American elites felt for Mysore’s cause. Philip Freneau, an ally of Thomas Jefferson and one of the country’s leading poets, wrote a poem in honour of the Hyder-Ally and its namesake, the sultan of Mysore:

From an Eastern prince she takes her name,

Who, smit with freedom’s sacred flame

Usurping Britons brought to shame,

His country’s wrongs avenging.

Clearly, nothing prevented these 18th-century Americans from seeing faraway Asian peoples as exemplars of liberty.

Despite Freneau’s optimistic vision, freedom’s sacred flame did not save South Asia. By the early 1780s, it was becoming clear that Britain would lose the war. Many Americans happily imagined a post-war world in which the East India Company would no longer be a significant force. Britain, however, managed to hold on to its territory in the Subcontinent, resisting the combined forces of Mysore and France.

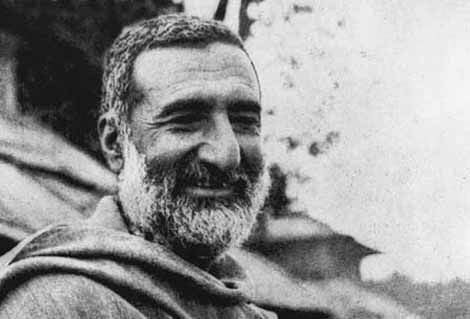

France’s military support for Mysore and the US helped drive it into crippling debt and push French society toward its own, more radical revolution. Meanwhile, Britain’s finances survived the conflict intact, allowing it to continue an aggressive policy in the Subcontinent after 1783. The cash-strapped French, however, could maintain only a token military presence in the region. The situation left Mysore’s new ruler, Tipu Sultan, to his own devices. He resisted mounting pressure from the British for nearly two decades, succumbing only in 1799. He died beneath the walls of his citadel as he fought a last-ditch battle against the East India Company.

The American government adjusted to the new realities of South Asian politics. New England merchants eagerly sought to trade directly with the Subcontinent. In the first years after the end of the Revolutionary War, they relied on the French colony of Pondicherry on the southeastern coast of the Subcontinent as a port. They soon realised however that they could not enter the region’s most lucrative markets without the permission of the British East India Company. They lobbied for the establishment of American consulates to foster goodwill for American interests. Responding to their pressure, the US government created its first consulate in South Asia in 1792, in Calcutta. Two years later, in Madras, they added another. American consuls in the region were responsible only for relations with the Company. They had no contacts with independent South Asian states such as Mysore, which the American government, like the French, left to fend for itself.

Only recently an enemy of the British empire, America had won independence and become Britain’s junior partner in empire

On a state level, American interest in Mysore disappeared. But many Americans remained fascinated by Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan. When Tipu sent a team of ambassadors to Paris in 1788, in an unsuccessful attempt to restore the Franco-Mysorean alliance, Jefferson, then the American minister to France, reported on the event with keen interest. Like Jefferson, a wide range of Americans were eager to learn more about Mysore. American newspapers of the 1780s and ’90s reported on the country’s desperate struggle with Britain. American textbooks, including Jedidiah Morse’s influential The American Universal Geography (1793), included sections on Mysore. Haider and Tipu seem to have approached the status of household names. In Williams vs Cabarrus (1793), a lawsuit brought before a circuit court in North Carolina, the two parties disputed a wager made on a horse race. One of the horses was named ‘Hyder Ali’ in tribute to Mysore’s former ruler.

Even in the wake of Tipu’s final defeat, in 1799, his struggle for an independent Mysore continued to echo in the imagination of Americans. In his sermon on 4 July 1800, John Russell, a Baptist minister in Providence, warned his audience about the dangers of British imperialism. While many Americans, such as Alexander Hamilton, advocated for closer ties to Britain, Russell insisted that Britain could not be trusted. The ultimate example of British injustice, he argued, was its conquest of Mysore. Deeply moved by what he saw as Tipu’s heroic resistance, Russell told his congregation of Tipu’s death at the hands of British soldiers: ‘here the full heart must have vent… [Tipu Sultan] defended his power with a spirit which showed he deserved it. His death was worthy of a king.’

For Russell, Tipu’s end ought to warn America about the mortal dangers of empire. By the early 19th century, however, America had embarked on its own imperial project. American missionaries fanned out across North America, travelled to the Levant, and poured into South Asia, writing glowing reports back home on the work that the British were doing to ‘civilise’ the world, including the Subcontinent. Only recently an enemy of the British empire, America had won independence and become Britain’s junior partner in empire.

American diplomats, merchants and missionaries in South Asia accepted Britain’s empire in South Asia, working alongside it to profit from local trade or proselytise to potential converts. Over the following decades, foreign policy officials, commercial interests and religious groups pushed for the US to acquire a colonial empire of its own. Just like the British empire Americans had once rebelled against, the US became an imperial power, with colonies stretching from Puerto Rico and Guantánamo in the Caribbean to the Philippines in the Pacific.

Today, with military bases in more than 70 countries across the globe, the US remains an empire. Yet, the generation of Americans who fought for independence from Britain and laid the foundations of America’s identity saw the US as an anti-imperial cause and nation. The founding generation and the children of the founders were fascinated with Mysore and its leaders because they thought Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan embodied American values of resistance to empire and aspiration to freedom. If later generations of Americans had continued to see Haider and Tipu as heroes, had continued to identify with underdogs and anti-imperial causes, then the US, and indeed the world, might look quite different today.

source: http://www.aeon.com / Aeon / Home> Essays / by Blake Smith / Edited by Sam Haselby / December 07th, 2016

___________