JHARKHAND :

Peter Gottschalk in his book Beyond Hindu and Muslim: Multiple identity in Narratives from Village India (2000) took a methodological leap to understand the multiple identities people carry in everyday lives. He carefully listened to the people talking about their local narratives regarding a fort; a temple dedicated to the ghost of a local Brahmin and a tomb that was probably associated with Bakhtiyar Khilji. While gathering the narratives of villagers of former Shahabad district of Western Bihar (during his fieldwork conducted in 1994-95) he tried to understand the significance of temporality and contextuality in assertion of identities.

Far beyond the monolithic religious binary of Hindus and Muslims, the identities get complicated with the presence of intertwined factors like class, caste, language, region, gender and nation. Not only that, the memory, context and existing narratives also shape the contemporary identities. For example, Gottschalk found lower caste Chamars claiming Hindu identity to establish their indigeneity against the Muslims, mostly considered as outsiders. But, similarly in the context of their exclusion from the upper caste village rituals, they assert their Chamar identity as opposed to both the religious groups.

Such assertion of identity becomes politically loaded through different means- mostly with the struggles for legitimate rights and in a few instances for establishing empathetic connection with the broader community. While working on Muslims’ presence in Jharkhand Andolon, what we encountered with is the assertion of a separate ‘Jharkhandi Muslim’ identity- sometimes it came as ‘Adivasi Muslim’, sometimes as ‘Moolvasi Muslims’. Whatever the lingual expressions be, the base of this identity assertion veers around their claims of being different from their North Indian coreligionists. Through the narratives and life sketch of different Andolonkaris, we learnt how this identity has shaped the presence of Muslims in Jharkhand Andolon. Jharkhandi Muslims in this context becomes both a constitutive and a derivative component of the broader statehood movement. To look into one without the other amounts to deliberate silencing of a politically effective assertion that had set forth the routes of the movement. This essay is thus an effort to find out the impact of this identity assertion in the Jharkhand statehood movement.

Muslims Kahan hai Jharkhand pe? – Story of A Composite Identity

Around 20 kms west from Ranchi, as we reached Simalia to meet Padmashree awardee folk singer and poet Madhu Mansoori Hasmukh, we found a place named, “Jharkhandi Muslim Hotel”. Though it didn’t come as a surprise as the complexities of Muslim identities in Jharkhand have been our companion throughout, what unfolded gradually made us literally silent. Barely we entered Madhu Mansoori’s house, we met Masi Zama, a social activist who use to come to his place for mundane cordial visits. On being asked what my research focuses on, I casually said, “It’s mostly on the Muslims in Ranchi, their silencing… participation…and…”. I was immediately stopped. His displeasure was though not reflected through his voice, the words he chose were enough to make us understand that we made a statement that we were ought not to. “Muslims? Muslims kahan hai Jharkhand pe? (Where are Muslims in Jharkhand?)”- for a moment I felt my whole research purpose, its objectives are dismantled to the core. “Ye aap logo ke tarah jo log hai uske liye yahan pe Muslims ka aaj ye haal hai (It is the people like you who are responsible for the conditions of Muslims in Jharkhand). When constituent assembly debates were going on why nobody spoke of giving Adivasi status to the Muslims of this region? Yahan pe Muslims nahi hai (There is no Muslim in this region) We are Jharkhandi Muslims, Adivasi Muslims… Moolvasi Muslims”, we were told.

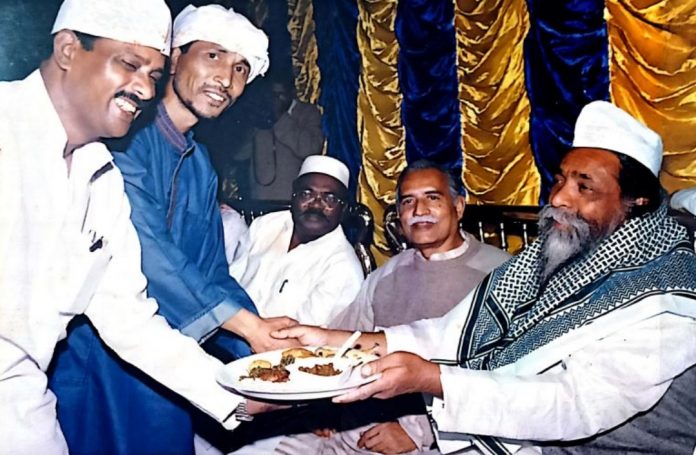

Understanding the gravity of the mistake as we were about to apologize, Madhu Mansoori, in his mid-70s entered the room. Without any ‘Salam-dua’ (Islamic ways of greetings like Assalam Aleikum Wa Rahamatullahi Wa Berakatahu) what he welcomed us with was a humble ‘Namaskar’. Already ashamed enough of our misconceptions, we greeted him back with a ‘Namaste’ and our conversation started. Madhu Mansoori claims himself as an Oraon Muslim. His ancestors, as he says perhaps got converted generations back. But it is the Oraon culture that drives his everyday lives. Throughout the interview whenever he referred to Muslims, he spoke off how the Munda-Oraon culture is intact within them. Islam has no conflict and doesn’t contradict their existing way of lives- rather it is a spiritual addition to the everyday beliefs and faiths.

These fundamental similarities rather embeddedness of faiths and practices into one another were explained to us later by Dr. Eliyas Majid, a Professor of History in Maulana Azad College, Ranchi. Explaining the Jharkhandi culture, he told us, “We have a ritual namely Madeikki Byebastha. It means helping one another in different things.” While in a capitalist set up, hiring laborers for mundane works is the norm, in Jharkhandi culture, as Dr. Majid said people come together to do neighbors’ works – whatever the nature of the work may be.

Another significant concept that Jharkhandi culture entails is of ‘Sahiya’ (friendship between any being or thing). “Koi bhi kisika Sahiya ho sakta hai. Ye zaroori nahi ke usko Insaan hona hai. Bachpan se jo aam, jamun ke paer pe hum khelte the wo bhi humara sahiya ho sakta hai. Hum logo me bahut sara ladki paer ke niche ghanto beithe rehte hai aur pooche to bolte hai Sahiya pass thi. (Anybody can become friend in our culture. It needs not to be human being. The mango, Jamun trees that we played underneath in our childhood could be our Sahiya. In our culture, women sometimes are found sitting beneath the tree for hours and on being asked where they have been- they respond- I was with my Sahiya)”, Dr. Majid continued.

The third and most interesting cultural attribute that he told us is called Gotiya’ (means brotherhood). For being brother in Jharkhandi culture, people need not to have blood relations. Any Oraon, Munda, Santhal can be Gotiya of a Muslim. All these three ideas explained to us by Dr. Majid significantly goes with the fundamentals of Islam. Helping others whereas is considered as Sunnat (Prophet’s (SWAS) way of life), the idea of recognizing every living being is in consonance with the belief of Islam that each and every being is created by Allah (SWT) and humans must behave with them in compassionate and empathetic manner. The idea of universal brotherhood (Gotiya) is also part and parcel of Islamic scriptures and commands. This comparison though is not intended to portray the similarities between Jharkhandi culture and Islamic fundamentals, rather it is just to show how Islamic fundamentals got melted into the Jharkhandi culture and paved the way for the construction of the identity known as ‘Jharkhandi Muslims’.

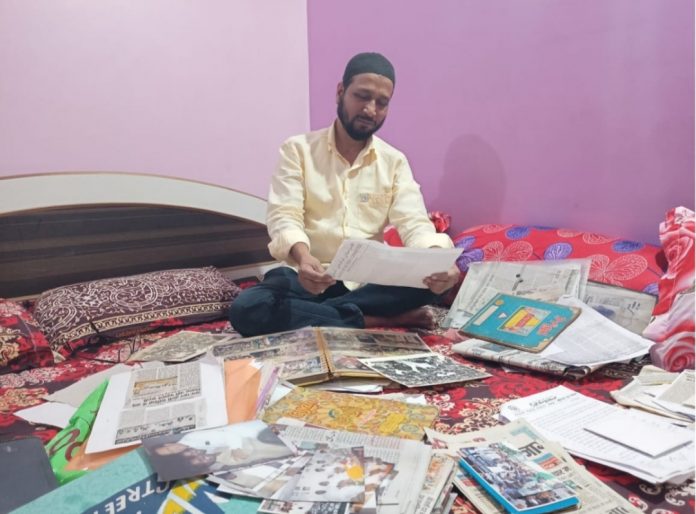

The cultural assertion of Jharkhandi Muslim identity whereas is rooted into the cultures of the land, the political assertion got its shape and voice through Jharkhand Andolon. Our encounter with Mohd. Faizi, a readymade garment seller near Upper Baazar took us through the terrains of this identity formation. Faizi made us walk in the roads where ‘Jharkhandi Manasikata (Jharkhandi Mentality)’ of Muslim foot-soldiers had to cross the paths of external political efforts and influences that were gathered to dismantle the ‘ekta’ (unity) of Jharkhandi Muslims.

Asghar Ali Engineer in his 1991 EPW paper ‘Remaking Indian Muslim Identity’ pointed out how ‘the assertion of religious identity’ could be a method for the ‘deprived communities in a backward society to obtain a greater share of power, government jobs and economic resources’. Similarly, assertion of Jharkhandi Muslim identity in the context of Jharkhand Andolon became a path to achieve the desired goals of statehood, to secure the rights of Minorities in the newly formed state and to ensure that ‘pehchan’ (recognition) of Jharkhandi Muslims remain intact without the imposition of homogenizing laws and regulations.

Personal is Political- Jharkhandi Manashikata & Instilled Mijaj

Mohd. Faizi was born in March, 1966 at Rain Mohalla, Tewari Street near Ranchi Main Road. Since childhood besides poverty another constant feature of Faizi’s life has been instilled ‘Jharkhandi Manasikta’ (Jharkhandi Mentality). Faizi’s father had a small (5ft/10ft) ‘Kapde ka gumti’ (an apparel stall) at footpath near Urdu Library. His childhood was filled with the stories of Jharkhand Andolon. Shared by his uncles, these stories instilled the dreams of separate Jharkhand in little Faizi’s mind. One of the stories was of an old woman who used to stay behind the Gel church (Evangelical) during the British Raj. Every day, ignoring the scorching heat, unbearable rain and all other obstacles she marched through the main road alone with a flag raising the slogan of ‘Jai Jharkhand, Jharkhand Prant Alag Karo’. The flag was nothing but a stick wrapped in a green cloth that became the bearer of Jharkhandi identity. She marched up to the Commissioner’s office and spending some time used to come back. Though there was no crowd behind her, the visual of her intermittent desire to have a separate state got reverberated through all those like Faizi’s uncles who later joined the movement in numbers.As people mocked at her, Faizi’s grandfather told them- “Yaad rakho ye mang jayes hai, aur ye aaj akeli nazar aarahai hai lekin ek waqt ayega jab iske peeche jan sailab hoge” (Keep it in mind that her claims her legit. Today, she is alone but day will come when hundreds will join her for the demands). Faizi not only witnessed the ‘Jan Sailab’ (Public uprising), rather he led it from the front and embraced it as a ‘farz’ (duty, mostly used for religious obligations) against all the odds coming in between him and his pledge to the separate state.

In his early age only, Faizi saw his uncles Tako Ansari, Mohd. Farooq joining the statehood struggle through N E Horo’s Jharkhand Party. In Faizi’s words, ‘Mijaj to thaa hi (Mood was always there). Along with that the devotion of family members to the cause of Jharkhand made these aspirations grow”.

Faizi had few friends like Shamim and Saajid with whom he started attending the meetings of Sadan Vikas Parishad (SVP). At that time, Prof. Shahid Hasan was the general secretary of SVP. It was very early stage of his engagement into the movement. However, two specific incidents changed the way he looked into the world thereafter. Due to his father’s deteriorating health condition he had to leave his education at an early stage. Still, in 1985, he appeared for the board exam. Though he scored good numbers in subjects like English, Arabi and Farsi, his marks in science and mathematics didn’t let him qualify the boards. He got only 2 marks less than required to pass the exams. There were other students as well with whom similar things happened and they decided to go to Patna Examination Board office.

The reality of blatant discrimination had hit him in an inexplicable way. While he and his ‘Jharkhandi saathis’ (friends from Jharkhand) were told that nothing could be done and they started preparing for the next year, students from Bihar started filling the forms of colleges. Faizi then got to know that his ‘Bihari Saathis’ (Friends from Bihar) were told by the officials to apply for reviewing their copies and got the required grace marks whereas they were told, “Yahan pe kuch nahi ho sakta (Nothing can be done here)’. This instance not only made huge impact on Faizi’s mind rather it made him further believe that ‘Ye maang Jaees hai, aur inse in Bihario se chutkara milna chahiye’ (The claims of statehood are legitimate and we must get rid of Bihari officials).

While referring to the second incident Faizi was red in rage. Sipping a bit of water from the glass that was kept near his bed, he continued- “It was 1987. For the first time, anti-encroachment drive was going on in Ranchi. Police forces and officers came to our small Gumti and asked us to immediately vacate it. They threatened us that if we don’t move, they would trample it on and would even charge fine. We didn’t have money- so we started dismantling out only source of earning. And as I was putting down the asbestos, a small piece of brick fell near an Officer’s feet. It didn’t touch him at all but he started abusing me with ‘Maa ki gaali’ (Slangs referring to mother). I felt like immediately hitting them. But no, I couldn’t. My ailing father was standing there along with my little brothers. I silently listened to them but pledged that I would take revenge. If not from them at least from their viradari (their kind). It was our time to get rid of all these brutal Bihari officers and polices- We had to achieve statehood- We must- for the sake of our existence- for the sake of having a dignified life”- Faizi was trembling- silence clouded the moment- tears were visible with the determination that led him to become one of the most committed soldiers of Jharkhand Andolon.

During this phase, he led a group of 10-15 youths who participated in different social works. Meanwhile All Jharkhand Students’ Union (AJSU) had already been formed and movement got its required momentum. One day, when they were sitting near Urdu library, Ranchi Main Road, Zubair Ahmed (then the Ranchi town secretary of AJSU) came and asked them to join AJSU. Zubair even brought the founder president Prabhakar Tirkey and arranged a meeting with Faizi and his friends.

Within days, for his oratory skills and determination, he became very close to Tirkey and other CC members of the party. “Kyun ki itne sare adviasio me ek Muslim chehra, upar se accha bakta (Among so many Adivasis, a Muslim figure with good oratory skills)” made people like him and Zubair stand apart. Along with Zubair and other Muslim leaders/members they started gathering Muslim support for the movement. Though Muslims’ presence had always been there since the very early days of Jharkhand Andolon, its further expansion and visibility became their objective.

Political Assertion of Identity- Jharkhandi Muslims and Foundation of JMC

Since then, what drive Faizi throughout was his desire to achieve statehood and the recognition of ‘Jharkhandi Muslim’ identity. The assertion of this ‘Jharkhandi Muslim Identity’ led people like Faizi or Zubair to invest their lives for the cause of separate statehood where they would be considered in same manner as their ‘Adivasi saathis’, instead of their religious brethren of the other states.

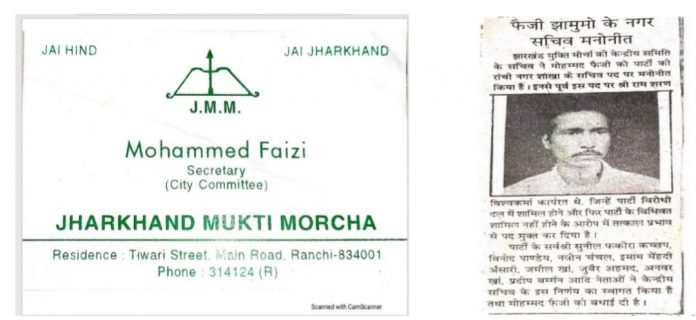

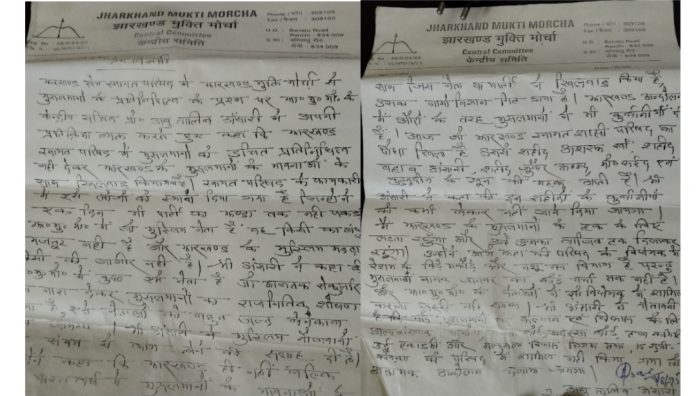

As soon as Faizi joined Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) in 1992 after a meeting with Prabhakar Tirkey and other leaders of AJSU (Tirkey faction) at Suleiman hotel, Lake Road, Ranchi, he got the chance to further work both for the statehood movement and the cause of separate Jharkhandi Muslim identity. The very next year in 1993, with the objectives of working for the social causes he founded Muslim Youth Forum. The organization though was not politically active, it could be called a social reform wing of the broader struggles for the Muslims in the state.Already Jharkhand Minority Front of Jharkhand Party was formed in 1988 and consequently in the next year Jharkhand Quami Tehrique (JQT) was founded. The founder president of All Jharkhand Students’ Union Prabhakar Tirkey in one of his articles in Prabhat Khabar titled ‘Jharkhandi Pehchan KeL iye Sanjida Rahe Musalman’ talked about the enormous participations of Muslims in the statehood struggle. His article even reflects what Mohd. Faizi has to say- “Jaise aapko pata hai Musalman bahut pehle se ye andolon me hai. lekin Musalman jo jude, kisi na kisi party se jude, aapna identity le kar ken ahi aye…Ab musalman ye tahriue ko aapne haat me bhi lenge aur tehrique chalayenge. (As you know Muslims have been part of this movement since very initial days. However, Muslims joined different parties and never came with their own identity. Now, it was the time for Muslims to lead the movement, to play the role of leaders not only the participants).On being questioned that why the Muslim identity became important at that stage, Faizi was more clear and vocal- “We have seen what has been the role of Muslims in Indian Independence. Even after that today Muslims are called ‘Gaddar’. Our histories have been deliberately eliminated. If we don’t create our own identity in this statehood struggle, people in coming days would definitely say that we had no role in the movement. We apprehended that in very early stage”. This was the reason why they not only fought rather as Faizi said, “We kept the documents as the evidence to prove that Muslims were no less in this movement and we made ‘barabar ki qurbani’ (equivalent sacrifices) like other communities”. Referring to ‘shahadat’ (martyrdom) of several Muslim leaders who died for the movement including Abdul Wahab Ansari, Qutubuddin Ansari, Murtuza Ansari, Mohd Zubair, Mohd Sayeed and Ashraf Khan, he implied, “Ye cheese Tarikh me jaana chahiye. Logo ko pata hona chahiye ki Musalman ye alag rajya ke liye kya kiye hai (It must be written in pages of histories. People must know what Muslims have done for the separate state).A Dr. Eliyas Majid had even mentioned in his book “Jharkhand Andolon aur Jharkhand Gomke Horo Saheb” that Muslims in the late 80’s needed their identities to be reflected on the grounds of the movements. On May 25, 1988 while presenting the working paper in the foundational Conference of Jharkhand Muslim Front (JMF), Dr. Majid said despite their participation and martyrdom, “Muslims utna hi cchipa hua hai, jitna Jharkhand Andolon ubhra hua hai” (Muslims are as much silenced as much the movement is vocal). His address majorly focused on two parts- firstly, the individual identity of Muslims and the political indifference toward their demands and secondly, the separate identity of Jharkhandi Muslims that share more cultural values with the Adivasi ‘saathis’ than their North Indian coreligionists. In words of Dr. Majid, “Jharkhand humara andolon hai, Jharkhand humare wajood se jura sawala hai” (Jharkhand is our movement, it is connected to our Entirety- our Entity).Even after this eternal connection with the movement, as Faizi says that Muslims were denied proper position in the histories of the struggle. “While writing the history of AJSU, people would talk about Suraj Singh Besra, Prabhakar Tirkey, Lalit Mahato, Mangal Singh Bobonga but nobody would mention Nazm Ansari, Farooq Azam, Zubair Ahmed or Mohd. Faizi. When JMM’s history would be drafted people would remember Shibu Soren, Suraj Mandal and Sailander Mahato but Prof. Abu Talib Ansari or Hazi Hussain Ansari would not be named”. His concerns later proved to be right as most of the accounts of Jharkhand movement hardly spoke of Muslim participation. They understood the fact that if only they would come up with separate organizations for Jharkhandi Muslims, it would be recorded in the pages of history.It was in early 1995 that the decision regarding the formation of Jharkhand Area Autonomous Council (JAAC) was taken. On the eve of it, Muslims of different Jharkhand ‘naamdhari’ (Jharkhand-named) parties came together to plan the formation of a specifically Jharkhandi Muslim platform that would talk about the condition of Muslims- that would ensure the constitutional rights of the community in the newly proposed state. During this period Qazi Mujahidul Islam of Imrat-e-Shariya was about to come to Ranchi. Hussain Qasim Kacchi, who used to be a keen patron of the movement asked Mohd. Faizi and his friends to meet Mujahidul Sahab. They planned a seminar on June 11, 1995 at Anjuman Plaza Hall, Ranchi Main Road to welcome Qazi Sahab. As there was no properly functioning Muslim front, they decided to use the banner of Qazi Sahab’s organization All India Milli Council.In Faizi’s words, “Banner didn’t matter to us, we had to do something to bring Jharkhandi Muslims together”. The title of the seminar was ‘Jharkhand Andolon aur Musalman’ (Jharkhand Movement and Muslims). Qazi Sahab while was the chief guest of the seminar, Prof. Abu Talib Ansari had presided over it. It was for the first time in the history of Jharkhand andolon that discussions happened in a public forum on participation of Muslims. Qazi Mujahidul Islam referred to the anti-racial movement in South Africa where Muslims stood by the colored people. This anecdote further worked as a spark as it not only echoes the ideals of Jharkhandi Muslims, rather it speaks directly to the fundamental tenets of Islam that commands its followers to join hands with the oppressed people of the world. He also called for an ‘umbrella’ organization that would accommodate all Jharkhandi Muslims.

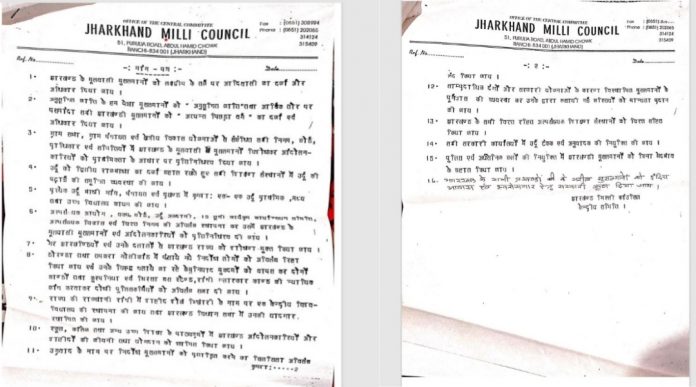

Following Qazi Sahab’s advice Muslim leaders of different Jharkhandi Parties called for a meeting on June 27, 1995 at Mohd. Faizi’s place. Around 252 representatives of different panchayats, social organizations and political parties attended the meeting and formed the Jharkhand Milli Council (JMC). As per the reports of Prabhat Khabar June 28, 1995, most of the leaders agreed to the contention that despite huge presence of Muslims in different Jharkhandi parties, they were not given due importance in decision making amounting to political silencing of Jharkhandi Muslims. So, the major objectives of JMC were to gain the recognition of Jharkhandi Muslim Identity (Moolvasi Muslim) along with claiming the legitimate political, economic, social and educational rights. To avoid the risk of catapulting another cult figure that the Jharkhandi parties had been the overwhelmed with, JMC decided to form a presidential council. Prof. Abu Talib Ansari whereas was declared the chief of the council, Farooq Alam, Mumtaz Khan, Prof. Khalik Ahmed and Salik Ahmed were the elected members. Nazm Ansari was projected as the Chief Secretary of the party and Mohd. Faizi, Sarfaraz Ahmed, Rafat Hussain, Abdul Moin Rizvi, Jameel Khan, Samnur Ansari, Mustaq Alam and Prof. Amin Ahmed became members of the secretariat. JMC pledged to not have any relation with the All India Milli Council, rather it decided to become a frontal organization for the Jharkhandi Muslims. Formation of JAAC- ‘Yahan Pe Muslim naam ka janwaar ka koi zikr nahi hai’Meanwhile, on July 30, 1995, Jharkhand Area Autonomous Council (JAAC) was formed and Shibu Soren became the chairman of the council. As anticipated earlier, almost negligible representations of Muslims in JAAC clearly made the fears of elimination legitimate. Protesting against the deliberate omissions of both Muslims and their causes Prof. Abu Talib Ansari wrote a press release on August 9, 1995. The release, however, could not see the light of the publication as Mohd. Faizi and other comrades restrained him from sending it to the press. As per Faizi, this declaration would have been considered as resignation of Prof. Ansari from JAAC leaving not even a single member in the council to voice the concerns of the Muslims. In the press release (collected from Mohd. Faizi) what we found was acute disgruntlement of Jharkhandi Muslims regarding the formation of JAAC. Prof. Ansari (then the Central Committee Secretary, JMM & Chief of Presidential Council, JMC) in the release said, “JAAC has played with the emotions of Jharkhandi Muslims by not giving them proportionate representations. There are few people in the council who didn’t even hold the party flag ever”.

Mentioning that the Muslim leaders of JMM are not ‘kisi ka bandhua mazdoor’ (bonded laborers), he continued, “Jharkhand is nobody’s paternal property. There are leaders in JMM who have used the slogans of secularism to undermine the cause of Muslims. JAAC is the by-products of martyrdoms of leaders like Ashraf Khan, Wahab Ansari, Zubair Ahmed, Mohd. Sayeed and Qutubuddin. These ‘shahadat’ should not be forgotten if an inclusive Jharkhand state is to be imagined.

Though there were references to Silk, Animal Husbandry and other departments in the JAAC bill, there was no mention of Muslims (Yahan pe Muslim naam ka janwaar ka koi zikr nahi hai). Prof. Ansari categorically warned that if Minority Welfare & Development Council, Minority Commission, Waqf Board, Haj Committee, Madrassa Board, Urdu Academy and implementation of 15 points program are not considered in the council, there would be parallel movement of Jharkhandi Muslims across the territories of JAAC.

Claiming Adivasi Status- Kohl Jolha Bhai Bhai

While JMC’s movements, processions and meetings across the territory of the proposed state continued with vigor, the major step of claiming their separate identity of Jharkhandi Muslims came on October 24, 1998 when the party leaders reached Delhi to submit petition to the then Prime Minister Atal Vihari Bajpayee. At Tal Katora stadium, New Delhi, JMC gave a protest call and was presided by Prof. Abu Talib Ansari. After the demonstrations, they submitted the petition containing the following key points-

1. The Moolvasi Muslims of Jharkhand must be given the Adivasi status and rights as available in Lakshadweep (As per Article 342 of Indian Constitution)

2. Like the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes, Pasmanda Jharkhandi Muslims must be given Economic and Political Rights

3. Jharkhandi/ Moolvasi Muslims and specifically those who have been part of Jharkhand Andolon must be given priorities in Gram Sabha, Gram Panchayats and any other developmental commissions and boards

4. Urdu must be retained as the second language and all of the educational institutions must have Urdu in its curriculum

5. In villages and towns Urdu schools must be opened for the development and retention of the language

6. Minority Welfare Commission, Waqf Board, Madrassa board, Haj committee, Urdu Academy need to be formed and Andolonkaris should be prioritized in these committees

7. Jharkhand should be free from the coercion of Non-Jharkhandis

8. A University under the name of revolutionary Sheikh Bhikhari must be founded in Ranchi. Jharkhand Legislative assembly also must have memorials of Bhikhari

9. In school curriculum, the lives and sacrifices of Jharkhand Andolonaris must be included

10. The trials of Muslim youths in the name of terrorism must be stopped

11. Places where the Muslim families had to resettle due to communal disturbances and riots must be given residential legitimacy

12. All the Government offices must recruit Urdu translators

13. Jharkhandi Muslims must be recruited in Security and Police forces without any discrimination

14. All the poor Jharkhandi Muslims should be given residential facilities through Indira Awas Yojana.

These claims clearly indicate the significance of ‘Moolvasi Muslim identity’. On one hand, it claims the status of Adivasis, on the other it demands to secure the rights of Minorities enshrined in the constitution. During our conversation, several times we found Faizi referring to incidents that show how Jharkhandi Muslims had been treated by Muslims of the other states. While being asked what was the positions of Muslims of other states (Northern India) vis-à-vis their struggles, Faizi lamented, “Koi samarthan nahi- birodh, birodh. Ye log nafrat kiya karte thee. Ye log yehi bat failaya karte the ki sara jo ye log Kohl ho geya hai. Ye log bolte the ki ye julus jalsa karke hariya daru kha ke so jaya karte hai. In logo ka hukumat karne ka mijaj ban gaya thaa. Aaj bhi ye log Jahan pe basenge chahenge ki wahan ki hakim hum ban jaye. (They never supported us. They told us that we have become Kohls. They have the perception that after Processions and meetings, we take hariya [a specific form of alcoholic drink made out of rice] and sleep. They got used to rule over us. Even now wherever they settle in, they want to become the owner of the place)”.

‘Arab ke sarjameen pe jaye toh hum jaye humari Jharkhandi Pehchan se’

Such emotion was reflected in actions of JMC even after the state of Jharkhand was formed. The demand of separate Haj Committee as mentioned earlier though was there since the formation of different Muslim Forums during Jharkhand Andolon, several Ulemas from Bihar said that for the first year (i.e. 2001) let the Jharkhandis be sent through Bihar Haj committee. Faizi and his comrades were not ready under any circumstances to have some compromises. “Itne jaddo-jehad ke baad jab alag rajya mila tabhi bhi hum jaye Haj karne Bihari pehchan se? Nahi! Hum chahte hai ki hum jab Arab ke sarjameen pe jaye toh hum jaye humara Jharkhandi Pehchan se (After so many struggles and fights we have got the separate state and still are we expected to go for Haj with Bihari identity? No! Never! We want when we will touch the land of Arab, we will have our Jharkhandi identity)”, Faizi’s words were reverberating in the room- the only thing that we could hear was the aspiration for separate Jharkhandi Muslim identity- even in the holy land of Islam where all other identities are subsumed by the broader identity of ‘ummat’.

On April 28, 2001, JMC submitted memorandum to then Minority Welfare Minister of Jharkhand Arjun Munda and asked him to form separate Haj Committee immediately. Under pressure the newly formed Jharkhand Government on July 2 declared the formation of separate Haj Committee in Jharkhand and Arjun Munda was made the president of 14 members’ council.

Faizi referred to another meeting of Momin Conference in late 90s in Irba where he further understood how Muslims of other states looked down upon them. The chief guest was from Bihar who not only continued comparing Jharkhandi Muslims with Kohl tribes rather he continued saying that Muslims in this state didn’t have manners of clothing and speaking. Only after the ‘Yalgar’ (attack) from the people of Bihar that they started learning the Islamic ethos. This savior complex of North Indian Muslims is what the Jharkhandi Muslims fought against.

Their opposition to the Ulemas from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh got reflected in the meeting of JMC on October 11, 2001. Under the chairmanship of Haji Akhtar Ansari, district president, JMC, this meeting unanimously took the decision of not letting the Muslim leaders of North to divide the unified Jharkhandi Muslim community. Such idea of united Jharkhandi Muslim identity though stands in contrast to the caste panchayats working at the mohalla level, it came several times in the words of Mohd. Faizi, Zubair Ahmed and other leaders as well that without the external interventions such ‘firqahs (sects and divisions)’ wouldn’t have much fodder to grow.

JMC continued its struggle for the rights of Jharkhandi Muslims and emphasized on the proper upholding of Article 29 & 30 of the Indian constitution. On one hand, the fight was against any sort of discrimination, on the other it was for gaining the recognition of a separate identity. Considering the backwardness of Muslims in terms of economic and educational qualifications, JMC submitted its petition to Arjun Munda, then the Minority Welfare Commission, on June 5, 2001 to provide the Jharkhandi Muslims with 20% reservation. JMC used the analogy of Karnataka’s Muslims as in late 90s they used to have 6% reservation within the cap of OBCs. However, the reservation of Muslims in Karnataka has different historical trajectories. Qazi Arshad Ali in his book ‘Karnataka Muslims & Electoral Politics’ mentioned that Muslims were given reservation as backward class back in 1921, according to the recommendations of Justice Miller committee that was appointed by Maharaja of Mysore. The context of Jharkhand was though totally different, the analogy of Karnataka was a point for them to show the possibility of using Other Backward Classes quota for overall development of Jharkhandi Muslims.

Against the Grains of Homogeneity

Till the date, though in an overwhelmingly communally polarizing situation, JMC is still working for the rights of the Jharkhandi Muslims. The lynching of Tabrez Ansari was the latest that made them sit together further to contemplate for what actually they devoted their lives- Is it the Jharkhand they hoped for? While we were about to wrap up the interview, Faizi asked his daughters to meet us. At a glance, we recognized Shireen Faizi who was one of the leading women faces during Anti-CAA movement in Ranchi. Faizi smiled at us- “Humara pura khandan hi Andolon se juda hua hai… Abhi bhi Jharkhandi Muslims ka koi bhi issue me pehla insaan jo raste pe ayega wo mere ghar se hi niklega…(My whole family is connected to movements. Still now, whenever Jharkhandi Muslims will fight for anything, the first person to come out of the house will be from our place)”- there was reflection of just pride that still helps him to sustain the struggles for existence.

At a time when Hinduization of Adivasis has become one of the major propagandas of the ruling Hindu rights, the nuanced ‘Adivasi Muslim’ identity must be further interrogated. Against the grain of religious homogenization where Muslims and Hindus, Muslims and Adivasis, Muslims and Dalits are pitted against each other as singular blocks, the assertion of ‘Jharkhandi Muslim’ identity becomes imperative at least to reclaim the Adivasi-Muslim unity in Jharkhand. For the survival of Indian democracy perhaps what we need the most is the recognition of heterogenous identities that have not been products of some decade-old propagated conflicts, rather have history of century old collaborations and bonhomie.

Authors:

Abhik Bhattacharya is a Doctoral Research Fellow, School of Liberal Studies, Ambedkar University, Delhi. He works on Silencing and Spatial segregation of Muslims in Ranchi

Arshad Raza Khan is the admin of Facebook page Muslims of Ranchi. He is also currently pursuing his M. Tech from Central University of Jharkhand

Ayan Tanweer is a Freelance photographer based in Ranchi. He is pursuing his M.B.A from ISB&M, Pune

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home> Must Read / by Abhik Bhattacharya, Arshad Raza Khan & Ayan Tasveer / October 28th, 2021