INDIA :

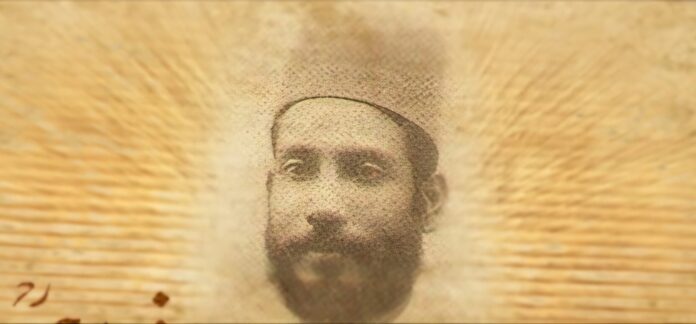

There are three ways of connecting with the greats, as they themselves tell us. First, dangle by their bootlaces and go just a little further than they did. Second, stand on their shoulders and see farther. Third, use their shoulders as a springboard and leap ahead. Allama Hameed ud Deen Farahi chose the third path and didn’t stop there; he went far beyond.

Farahi was a seeker, unmindful of the commotion around him. He ventured into uncharted territories, undeterred by fear. This is what made him extraordinary.

When Iqbal discussed Muslim political power in the Indian subcontinent, Muhammed Pickthal held a differing view. Pickthal believed that Muslim society was too degenerated and required all efforts for its recovery. For him, any struggle for political power in such a decayed state was unwise. Farahi, with the calm focus of his personality, carved another path: the path of knowledge. For Farahi, everything else stemmed from this pursuit.

This does not mean others were unaware of the need to restructure knowledge. Leaders like Sir Syed, Shibli, Iqbal, Abul Kalam, and other Muslim intellectuals recognized the importance of reviving Muslim knowledge. However, Farahi stood apart. While others were deeply engaged with the history and sciences of the Muslim world, Farahi placed the Quran at the very center of Muslim knowledge. He focused exclusively on the Quran, making everything else secondary.

Although many of us profess the Quran’s supremacy in an emotive sense, we often compromise its sovereignty in various ways. Through tradition, history, jurisprudence, mysticism, philosophy, and the ever-looming image of empire, we carve tunnels into the Quran. Farahi, however, stripped his mind of these distractions and approached the Quran through its own lens. He deciphered its language and found it coherent. This was a monumental discovery. But what does this coherence mean?

Charles Mackay’s masterpiece Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds offers an intriguing perspective on human tendencies. He illustrates how we “love the marvellous” and “disbelieve the truth” through an exchange between a sailor and his mother. The sailor tells his mother, “As we were sailing over the Line, we saw a fish rise out of the sea and fly over our ship.” The mother, incredulous, replies, “What a liar you are!” A simple fact of marine life seemed utterly untrue to her.

Sensing her skepticism, the son adds: “We saw even more wonderful things than that.” The mother, intrigued but still dubious, responds, “Let us hear them, and tell the truth, John, if you can.” The son continues, “As we were sailing up the Red Sea, our captain decided he wanted fish for dinner. So, we cast our nets, and on the very first haul, we brought up a golden chariot wheel, inlaid with diamonds.” This piques the mother’s curiosity. “What did the captain say about it?” she asks. The son replies, “He said it was one of Pharaoh’s chariot wheels, lying in the Red Sea ever since that wicked king was drowned while pursuing the Israelites.” This fantastical tale satisfies the mother, who exclaims, “Tell me such stories as that, and I’ll believe you; but never talk to me of such things as flying fish!”

Mackay concludes that in a contest between the “wondrously false” and the “wondrously true,” the false often wins. When Farahi’s ideas are applied and his discoveries are brought to light, even reasonable minds recoil. His work disrupts entrenched ideas, much like the flying fish, which many deny while embracing the chariot wheel. Spectacular dullness frequently eclipses spectacular brilliance.

In today’s world, where Islam and power politics are wildly entangled, applying Farahi’s insights is doubly challenging. A closed, stagnant mind may merely dismiss the flying fish. However, a mind intoxicated by power and frenzy may go further and destroy it. General acknowledgments of Farahi’s greatness are easy and often met with applause. But when one begins to question deeply held ideas and ideals, decency is often forgotten.

Here, Farahi’s character may be as vital as his knowledge. Those who knew him observed that it was hard to decide which was greater: his knowledge or his piety. His saintly heart was fused with a philosopher’s mind.

When Farahi proposed the coherence of the Quranic text, even Shibli, initially unconvinced, eventually came around. Through further discussions, Shibli recognized the idea’s merit. In one of his letters to Farahi, he wrote: “From now onwards, I will study the Quran with attention to the order in the verses and get back to you.” This humility, especially from someone who once taught Farahi, is remarkable. It takes both a perceptive mind to judge greatness and an unbiased heart to acknowledge it. Shibli realized that the flying fish in the Red Sea was indeed real.

Shibli later wrote to Hamid: “I have thoughtfully read your commentary on Surah Abi Lahab and parts of your work Jumahratul Balagah. I congratulate you. All Muslims must be grateful to you for this.” Shibli didn’t mind the old ideas being displaced in light of Farahi’s discoveries. True seekers carry no idols. They only bear a cross on which biases and disguised reverences are crucified.

In the pursuit of truth, losing cherished ideas does not matter. What matters is the truth itself. This pursuit brings humility, and the knowledge gained on this path nourishes and revitalizes, like rain on parched land, fostering growth rather than igniting fires.

Today, those inciting violence in the name of Islam are fueled by delusions perpetuated by preachers and demagogues, stories akin to Pharaoh’s chariot in the Red Sea. This collective madness includes Kashmir, where we are complicit. Farahi would have no interest in catering to our delusions. He would simply assert that there was a flying fish in the Red Sea and no more.

source: http://www.muslimmirror.com / Muslim Mirror / Home> Opinion> Religion / by Ramiz Bhat / March 05th, 2025