Lalitpur (Jhansi) & Agra (UTTAR PRADESH) / London, GREAT BRITAIN with Empress of India

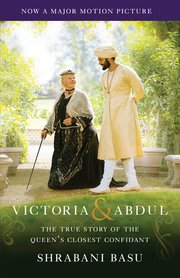

VICTORIA & ABDUL

The True Story of the Queen’s Closest Confidant

By Shrabani Basu

Illustrated. 334 pp. Vintage Books. Paper, $16.

I really do wonder if I am qualified to review this remarkable work. I am a nonagenarian, Anglo-Welsh, republican, agnostic liberal, an only half-redeemed British imperialist, sexually complex and incorrigibly romantic. “Victoria & Abdul” is about an aging British queen, her eccentric obsession with an engaging Muslim servant from India and the half-farcical opposition of the British establishment to their relationship. I had never heard of the story until the book reached me for my critique, and I had no idea it was about to be the subject of a much-publicized movie. Am I qualified to respond to it for The New York Timer? Reader, judge for yourself.

When it first reached me I began, as a republican, by scoffing. The very status of Alexandrina Victoria, Queen of England, at the time of her first encounter with that Indian servant struck me as perfectly ridiculous. She was a woman in her late 60s who was treated with almost religious reverence and responded accordingly. The whole preposterous charade of royalty was performed perpetually in her presence. It was wildly exaggerated, too, because she happened to be the titular head not simply of a small island nation but of the most enormous empire in the history of empires, claiming sovereignty over nearly a quarter of the earth’s surface. Perhaps the least logical of these bizarre circumstances was the fact that among her far-flung territories was one of the proudest and most ancient of all human entities, India. Since 1877, Victoria had been called Queen Empress, and India was the reason.

I scoffed, but then that Indian charmer entered the book, and I was beguiled.

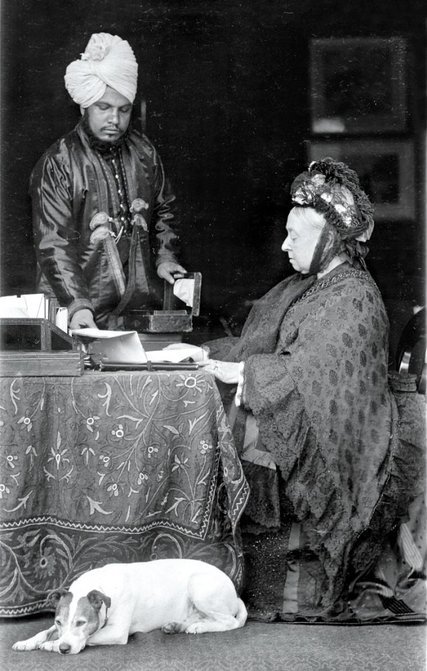

So was Victoria. Abdul Karim was 24 when he arrived in England in 1887, engaged as an orderly for the queen during her Golden Jubilee celebrations and presently also charged with teaching Her Imperial Majesty Hindustani (as the British habitually referred to both Hindi and Urdu). Although of relatively humble stock, he was a born winner, educated, good-looking, clever and ambitious. I soon fell for him myself.

In no time at all, it seems, he became far more than an orderly, but rather an Indian gentleman of the court, more or less self-promoted out of the servants’ quarters and dubbed, by Her Majesty’s command, a “munshi” — which meant, I gather, a sort of more-than-teacher. This in turn seems to have morphed into a vaguely aristocratic honorific, and before long the delightful young orderly had become the Munshi. For the rest of his life he flaunted the title, and “Bravo,” say I!

I find myself genuinely touched by the bond between the empress and the munshi. He was an opportunist, but he was kind, which for my money redeems many faults, and old Victoria had been having a rotten time of it. First she lost her adored husband, Albert, and never got over it, and then John Brown, her beloved Scots gillie, died on her. Victoria’s nine children were scattered across Britain and Europe, and they were a mixed bag anyway. It must have been a lonely time for the old lady, but then along came Abdul Karim, in his virile youth, and he was very soon treating her not only as an empress but as a woman.

There was obviously nothing carnal about the relationship. Heaven forbid! The munshi seems to have regarded Victoria as an affectionate and generous surrogate mother. (She gave Abdul Karim and his wife three cottages, each near one of her own palaces, plus some land in India, and when he traveled on the royal train he had a whole carriage to himself.) In return he gave her his sympathy and understanding, and in particular they both seem to have enjoyed her daily (and very successful) lessons in Hindustani.

The affair, if we can call it that, spilled over into the style of the British court, which became more and more Indianified. Indian colors were everywhere, Indian sounds and even Indian smells (for curries were often served). When the court indulged itself or its visitors with one of its elaborate tableaux vivants, Indian faces were prominent on the stage, and indeed in the tableau of the king of Egypt, pictured in this book, the Pharaonic ruler himself was played by none other than — the munshi!

The generally snobbish and often racist British establishment of the day came to detest the munshi with an almost comical fervor, and, led by Victoria’s son and heir, Bertie, who later reigned as Edward VII, persecuted even Abdul Karim’s memory when he and his love were both long gone. I suspect that the munshi was a sort of dual reincarnation of Victoria’s beloved Albert and her dear, dear John Brown. And if there was something rather excessive — even, to my mind, schoolgirlish — about her attachment to her young servant, it was perhaps only a late and pathetic extension of the maternal instinct.

I grew fond of them both as I read this generous and meticulous book, and I write this review now with a sentimental tear in my eye. So what think you, Reader? Am I qualified for the job?

_____________________